Joan Holland (or Mrs. Holland, as her students affectionately call her) has made a musical mark on hundreds of harpists—including me—over the course of her 43-year career. I first met Mrs. Holland in 2015, at the beginning of the Interlochen Arts Camp. She greeted my family and me with open arms and a heart of gold, exuding excitement to begin working together for the summer. Those six weeks at camp led to two academic years at the Interlochen Arts Academy continuing my studies with her. Deep in the Northern Michigan wilderness among the stately pines, young harpists donning signature powder blue polos and navy bottoms discover profound musical growth and awakenings under Mrs. Holland’s guidance.

In addition to teaching at Interlochen’s academy and summer camp, Holland is an associate professor of harp at the University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theatre, and Dance. She began her studies with Eileen Malone at the Eastman School of Music’s Preparatory Department and then studied with Alice Chalifoux from age 12 through her undergraduate degree at the Cleveland Institute of Music. She is the principal harpist of the Midland Symphony, Great Lakes Chamber Orchestra, and Lexington Bach Festival Chamber Orchestra, and co-principal of the Traverse Symphony Orchestra. Holland also performs frequently as a chamber musician with her trio, as well as with her husband, violist David Holland. Her passion for teaching has made her studios at Interlochen and University of Michigan hot spots for young harpists who are striving for professional careers. I had a chance to catch up with Mrs. Holland over the Thanksgiving holiday to find out more about her teaching principles and inspirations.

(L.) Joan Holland with student Hannah Allen at her graduation from the Interlochen Arts Academy; (R.) Holland with University of Michigan graduate student Amber Carpenter.

(L.) Joan Holland with student Hannah Allen at her graduation from the Interlochen Arts Academy; (R.) Holland with University of Michigan graduate student Amber Carpenter. Joan Holland (far right) with students past and present at the Interlochen Arts Academy in Northern Michigan where she has taught for 43 years.

Joan Holland (far right) with students past and present at the Interlochen Arts Academy in Northern Michigan where she has taught for 43 years. “I love when people are freer so that their voice can come through more easily on the instrument,” says Joan Holland, pictured far left.

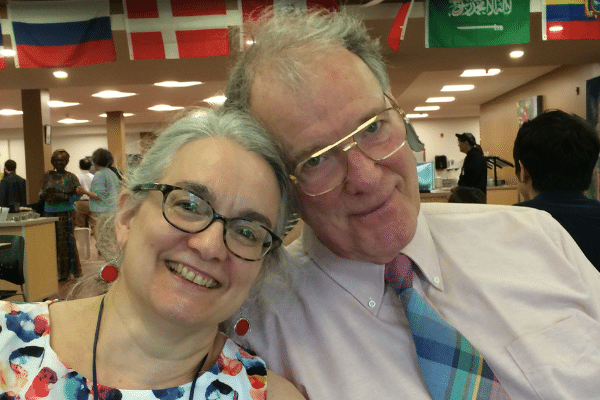

“I love when people are freer so that their voice can come through more easily on the instrument,” says Joan Holland, pictured far left. Joan Holland with her husband of 41 years, David Holland, pictured here at an Interlochen Arts Academy graduation. The couple met at the IAA where David was teaching viola and Joan came to teach harp.

Joan Holland with her husband of 41 years, David Holland, pictured here at an Interlochen Arts Academy graduation. The couple met at the IAA where David was teaching viola and Joan came to teach harp. Holland with her U of M studio following a recital.

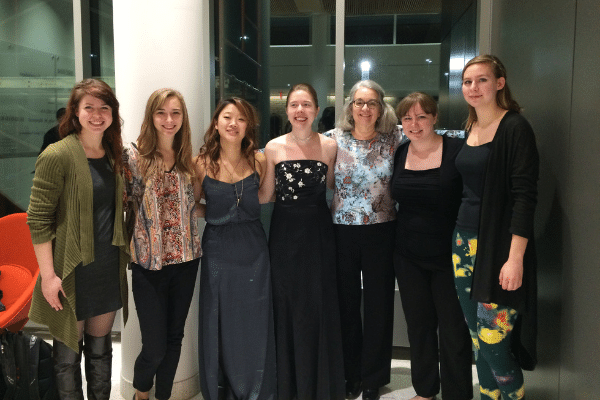

Holland with her U of M studio following a recital. Holland (second from left) and several University of Michigan students enjoy some post-recital laughs following Carly Nelson’s (third from right) performance.

Holland (second from left) and several University of Michigan students enjoy some post-recital laughs following Carly Nelson’s (third from right) performance.

Harp Column: What are some of the things that you love about the harp?

Joan Holland: I love its resonance, how it rings—that’s what I love about the harp. Although we have to muffle, I love the intrinsic nature of the instrument’s ring. I also love the keyboard-type music that we play; I’m drawn to that.

HC: You studied with prominent pedagogues from your first days at the harp. Would you share more about your teachers and their influence on your own approach to the harp and musicianship?

JH: I started with Eileen Malone, who was principal harp of the Rochester Philharmonic and taught at the Eastman School of Music. We lived in Pittsford, New York, about half an hour away from Rochester, and I used to take a city bus to and from Eastman. My parents would put me on this bus, when I was 10, and I would travel with transfers down to Eastman! Most of the time I was fine, but there were some times that I got lost and a bus driver would have to help me! [Laughs]

When you give a solo recital and feel like the music is just spinning out—that’s magical.

I was studying piano there, and Eileen Malone was giving harp lessons for free because Lyon & Healy was paying her to do so. All we had to do was rent a Troubadour for the year, which I shared with another student. I remember the lessons being very kind, very formal, and serious, with great regard to the music, no matter what the level. She taught me so much respect for whatever piece of music was on the stand. She taught me right away to close into the hand and maintain a supple wrist, right from the beginning. Then when I was 12, we moved to Akron, Ohio, and I started studying with Alice Chalifoux. I also studied piano with Nicolas and Rosalie Constantindis, both of whom really informed my approaches to musicality. Ms. Chalifoux started teaching me, with a slight alteration to my hand position and arm position. There have been several different variations of the Salzedo methodology, as it evolved amongst his students and harpists, and I learned from Ms. Chalifoux about the beautiful angle of the hand. Slight adjustments in the angles of the hands allow for full closing and a big sound, and I remember this being very prominent in her teaching. She was also very respectful of written dynamics, and insisted that we pay attention to the composer’s indications. A really beautiful thing that she used was shading—she wanted us to think about the shadings in our music. It isn’t black and white, it’s subtle; it has movement. I studied with her for nine years, but I never felt bored. She was very down to earth, and would cut to the quick if you were unprepared in your lessons.

HC: How long have you been teaching at Interlochen and at the University of Michigan?

JH: I’m entering my 43rd year at Interlochen, and started at U of M in 2008, entering my 13th year.

HC: Your teaching career began very early at Interlochen, at both its storied summer camp and prestigious boarding school. Tell us what makes teaching at Interlochen unique. How is it different from teaching students of this age in traditional settings?

JH: Well, receiving any kind of private study will deeply nurture a student, regardless of the setting. A major plus about being at Interlochen is that you’re surrounded by other teenagers who are learning to hone their disciplines, talents, and skills; investing themselves in their art; and understanding that it’s a process. They’re surrounded by each other with this, and it creates a huge support group. It’s exciting and stimulating, and it’s an environment where everyone is learning to develop themselves and reap the rewards of supporting each other’s productions. Another terrific thing about it is being shoulder to shoulder with other teenagers, seeing that so many areas of the arts work in the same way. The journey and process are very similar, whether you’re using a paintbrush, doing your daily warm-ups, or playing for other people and getting feedback. It’s all kind of the same journey, and I can sense how rewarding that is for students. I wish I could’ve gone to Interlochen as a student. It’s also small enough that there’s plenty of leeway for collaboration. I just love walking through the lunchroom and seeing these students discuss a piece of music or a masterclass they just attended—it just rolls off their tongues.

HC: What is it like teaching at University of Michigan? How does it differ from the environment at Interlochen?

JH: The main thing is that the students [at Michigan] are much more independent. They’re testing the waters and learning to work independently—it’s a taste of the real world for them. One of the things that’s very inspiring to me is the variety of ages. I have ages 18 through mid- to late-20s, and it’s super heartwarming to see how these different ages mix together and support each other. You can have some pretty extreme, youthful attitudes, juggling their class loads and taking care of themselves, and I’ve seen that the older students will help and kind of lead them through their early stages of school. There’s also a huge variety of repertoire, and it’s kind of mind-blowing for everyone to be thrown into a pool of so many types of music. Solo, chamber, and ensemble music, as well as contemporary music—they’re surrounded by it all. It’s a wide span of maturity and experience, and they all learn from each other.

HC: What are your favorite parts of teaching students at both Interlochen and University of Michigan?

JH: I like to help set people up, to try to have my students rid themselves of tension that makes it hard to play and makes it hard for other people to listen. I love when people are freer so that their voice can come through more easily on the instrument. I teach the tenets of harp playing that I feel are essential to relaxed playing, enabling the instrument to speak on its own. I have everyone focus on warm-ups, especially closing and focusing on bringing the fingers into the hand. I use the term “closing down,” as it allows for an easier mental approach to playing through the strings. We work a lot on being aware of unnecessary tension at both schools, especially thinking about having our wrists open. I talk a lot about avoiding roadblocks in our arms, to keep everything open so that the power goes through to your fingers.

I love studying all the repertoire, all of the standards. I don’t get tired of them…at least not most of them. [Laughs] At U of M, we can jump in sooner to musical crafting and coaching someone on their performances of repertoire.

I love teaching new music, and, especially at U of M, I’ve been exposed to a lot of music that I hadn’t heard or studied myself. I love to finger my students’ music and to give them pieces that are marked so that their playing is initially organized. I love having kids set up, not only technically, but also with a musical process and definitely with fingering that makes the harp not sound awkward. I want it to sound smooth and easy, even if it’s staccato. I just like working with people, their different personalities, and trying to figure out how to help them develop at the harp. Even teaching people something that they don’t like initially, we’re able to find an approach that allows them to play the music with purpose and sound really good.

I really love having people discover the musical power of the accompanying lines and harmonies. That’s like magic, having the melody take on a whole new shape with an informed accompaniment. That’s really fun. It’s all so rewarding.

HC: During your time at Interlochen, the school has grown and evolved dramatically. What sorts of changes have you observed in the students who come to Interlochen over the course of your career?

JH: Aside from some of the new majors and definitely all of the new buildings that make life so much easier, the serious and passionate students are still serious and passionate. Even when we were in our older buildings, the focused kids were not any less focused or intense than the current student body. The intensity of purpose and love of their art has not changed. The campus is beautiful, and its natural surroundings haven’t changed. The students are still wanting to pursue and learn.

Find out more about Joan Holland’s travels around the state of Michigan.

HC: You’ve taught at summer camps at Interlochen and Michigan for years—what is it about the summer camp experience that is important for harp students to experience?

JH: The best parts about summer camp are that it’s this intense, short period of time; it’s a chance to throw yourself into your playing and know that you have to do some things more quickly than other times to take advantage of the brief time at camp. Students come in with a sense of “this is very meaningful time, let’s get going.” In the same regard, they experience a lot of new learning quickly and have to apply it fast, but they also do it with their hearts! They have to open their hearts. Well, they don’t have to, but subconsciously they do, and end up making lifelong friendships and connections in far less time than during the academic school year. It’s interesting, and it’s kind of the magic of a summer camp. I think that powerful changes and decisions can be made during a summer camp.

HC: You have such a structured and effective approach to teaching all types of students. Can you tell us more about your own approach to the harp—is it structured similar to your teaching methods? What do you find to be the most important elements of playing the instrument?

JH: I always warm up using the Larivière exercises—they just cover so many bases. I pull from the Salzedo Conditioning Exercises, the Daily Dozen, and Yolanda Kondonassis’ “Warm Up No. 3.” I realized that warming up is very important when I had children, and boy does it make a huge difference. I play, and I relax, and I’m conditioning myself and my body to “release.” I’m always aware of my middle two fingers being the center of my hand, and this centering of the second and third fingers has really been helpful to me. I’m sure I’ve been taught this, but in the past 10 years, I’ve taken this on, and it helps me so much. I always have some new pieces on the docket. I’m currently learning the Jongen Trio and Gilad Cohen’s Trio for clarinet, cello, and harp. I’m always inspired to play Baroque music at the concert grand harp, and I’m always working on transcriptions.

I use the same approaches that I teach, especially with posture and the torso’s core support. It’s our tree trunk. I find that the angle of the hand opens so many doors for the matter at hand. How you face or angle away from the strings is kind of a miracle. I love the fullness of the palm—I find that it really helps the fullness of sound when you focus on using your full palm. I love gestures and the various ways to move the sound waves from the harp to reflect your musical intent. I try to have students stay closer rather than move very far from the strings, but I’m still amazed by the physics and impact of a raise on the harp’s tone. I love the stabilization of the middle two fingers to center the hand. This brings out the middle sounds and tone, and provides so much warmth. As far as musical tips, I focus on and encourage using your ear—having the ear engaged and having the ear guide the playing, pulling the wagon. It’s kind of a miracle, a unique mode of concentration that makes everything more natural in the delivery. I try to help people with this, mainly by having someone sing a line to connect the playing to the ear. Really, the most interesting part is seeing the student use the inner ear to identify which notes were present or absent, and they always seem to hear it for themselves once you acknowledge it. We can work together from there to bring every note to life.

HC: You’ve taught scores of students over the years—are there any common characteristics in your best students? What do you think makes a good harp student?

JH: The easiest students to teach are the ones that are internally motivated, or at least have a desire to learn motivation. A lot of students seek external motivation like a recital, but inner motivation is key. An openness of communication about what works, what is confusing, what doesn’t work—it all helps. A willingness to do the maintenance and steady work, and the realization that inspiration is not a constant, but consistency will bring pretty regular doses of inspiration. That’s not something a young person might know immediately, but it is important. You can have some really inspiring days if you maintain your steady application. They also use the lesson information throughout the week. The lesson provides a springboard for personal discovery and progress. I think it’s awesome that students can go back and listen to their recorded lessons—it’s incredible. When students go back and take notes on their lessons, they’re able to connect the dots and use the information to guide their practice for the week.

HC: What skills are most lacking in the students you see today?

JH: Patience and willingness to do the non-glamorous work. I’ve had a couple of students say “I used to like the harp, but it isn’t fun anymore,” and I think that means one of two things. First of all, it means that they haven’t really learned how to work in depth to discover what they really could do, but it also means that maybe they discovered that they don’t want the harp to be their career. Maybe they just want to enjoy playing as their pastime, and not the central focus of their life. Also, inconsistency and not using the lesson information both lack at times with students.

HC: What is the most helpful piece of advice you’ve ever received in regards to pursuing a career as a musician?

JH: I would say that one of the first things is my husband’s words, “Just get to the harp.” I tend to create these mountains of tasks of things that I need to accomplish, and it can get so overwhelming that I forget how much I like to play the harp. It’s helpful to just sit down at the harp and get the work done. My husband is a great practicer, he will get in 20 minutes whenever he can or just practice forever. So that’s one great piece of advice that has helped me, and I try to do it as much as I can. Also, a quote from Itzhak Perlman, “Have patience. If you sound good on Monday, and not so good on Tuesday, have patience. It just means it isn’t there yet, and that it will be better on Wednesday.” It’s just helpful for me to think about, trusting that we’ll get there eventually.

HC: Tell us a little more about your husband, David.

JH: I met David Holland at Interlochen when I first started. He was the viola instructor, head of string chamber music, and head of the string orchestra. We decided to play the Bax Fantasy Sonata for viola and harp. It forced us to be in the same room together, because otherwise we were always fighting. [Laughs] It was a long venture, but now we’ve been married for 41 and a half years. We have two kids, Jennifer and John, and our son-in-law, as well as two terrific granddaughters who love to sing.

HC: What is one piece of advice you’d like to share with young harpists reading this article?

JH: In general, get the notes off the page and into your own world of sound, message, imagination, and expressiveness. This cannot truly be done without solid and relaxed technique, but musical freedom is also an investment of time and shaping of one’s musical spirit. The physicality of form and extreme suppleness are crucial together, allowing the player to sing their lines and all of their moving parts. It is amazing to experience the beauty and power that opens up a piece as the accompanying harmonies and lines thrive and direct [the music]. Just starting to hear what they have to contribute can be a moment of truth in the music.

HC: What are some of your favorite pieces to teach?

JH: I like teaching almost all music. Depending on the student, some pieces take on a new life under their fingers. I do enjoy teaching music that’s somewhat programmatic, like Renié’s larger works. I love teaching Scintillation by Salzedo, it just always evolves with each harpist. The C.P.E. Bach Sonata is wonderful, especially the second movement is so beautiful and can be so expressive. I love to teach the Tournier Sonatine, Tailleferre Sonata, and really all of Debussy’s works—both the transcriptions and original works for harp. I enjoy all the standards and coaching chamber music.

HC: When you think back on your teaching and performing career, what are the moments that stand out?

JH: Definitely the moments when I felt like I was in a musical zone. When it all happens in flow without physical exertion. The connections between chamber musicians, the connections between students and teachers when the lesson flies by. When you give a solo recital and feel like the music is just spinning out—that’s magical. Time stands still, and you realize the importance of music and the harp. I also have to say the relationships and journeys of working and being with people, especially students, are precious and really stand out. And all the people that I’ve met in my career—including the hosts who help with logistics—I love those relationships too. •

Making music in the mitten state

Joan Holland knows her way around the state of Michigan pretty well, criss-crossing the mitten state to teach at the Interlochen Arts Academy and Camp in the northern Lower Peninsula, performing with symphonies throughout the state and neighboring Canada, including Traverse City and Midland, and heading up the harp department at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Knickers or pants? Pants.

Cold weather gear you don’t leave home without? Mittens, a sturdy snow shovel, a bag of sand in case you’re stuck, a hat, and good boots.

Boat or beach? Beach, unless it’s a pontoon.

Favorite food? Pasta, and really good meatballs.

Worst snow you’ve ever moved a harp in? I remember one time I was playing with the Sault Symphony, up in Sault Ste. Marie, Canada. I had gotten the harp into the car and was going to take the harp out of my car into my host family’s house, and the sliding door came off of my car in my hands. On top of that, the back wouldn’t open, it was frozen shut. So that was bad.

What would you do for a living if you weren’t a harpist? Maybe I would be a French teacher! Not that I speak French well now, but I did enjoy it. That or a costume designer.