Opening the score of Debussy’s Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp for the first time can be overwhelming, even for the most seasoned harpist. In fact, that is exactly the word used by many harpists when asked about their first experience with this pillar of the classical harp repertoire, commonly referred to simply as the Debussy Trio. Not only is it the piece that essentially started the genre of the harp trio, but it is also written by one of the most revered and beloved composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Trio is a work that is often required of serious pedal harp students around the world and is extremely challenging in both its technical and interpretive requirements. If you are new to this work, by the end of this article you will have a game plan for learning and performing it with confidence.

But first, a little background

Debussy filled his scores with instructions to the performer…the sheer volume of tempo, dynamic, and articulation markings can be almost paralyzing.

Achille-Claude Debussy was born in France in 1862 and entered the Paris Conservatory at age 10. He studied piano and composition along with the required solfège and theory. Debussy developed a style of composition that defied the rules and conventions of the past, creating his own unique harmonic language and form. As Stephen Walsh wrote in his biography Debussy: A Painter in Sound, “…few composers ever had so precise an image of the music they wanted to write, and even fewer have been so ruthlessly meticulous in the search for the exact expression of that image.” Debussy filled his scores with instructions to the performer for how to achieve the expression he sought. While to some this is helpful insight into the composer’s intentions, to others, the sheer volume of tempo, dynamic, and articulation markings can be almost paralyzing. But if you look at those instructions with knowledge of Debussy’s background, style, and sense of musical color, they can be more help than hindrance in achieving the lightness and suppleness of the music Debussy wished to create.

As harpists, we are all familiar with Debussy’s Danses Sacrée et Profane, originally written for chromatic harp in 1904 but transcribed only six years later for pedal harp by Henriette Renié. It has become a part of the harp concerto canon and is one of the most programmed pieces for harp solo with orchestra. Many harpists who play orchestral repertoire will have performed works such as Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, Images, La Mer, and Nocturnes that have become standard repertoire and require two harps in the orchestration. We also have some of Debussy’s piano works that have been transcribed for harp by many harpists. Debussy’s use of color makes his music especially suited to performance on the harp, and we have appropriated much of it into our standard repertoire.

The Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp is in a class by itself, however. It was written as part of a planned cycle of six sonatas for diverse instruments, but Debussy died after completing only three. Written after the sonata for cello, but before the violin sonata, the trio was originally to be scored for oboe instead of viola, but early in the piece’s conception, Debussy changed the instrumentation to the viola, as is evident from his sketches for the piece. There is an often-quoted remark that Debussy made about the Trio sonata in a letter to his longtime friend Robert Godet. “It’s frightfully melancholy, and I don’t know if one should laugh at it or cry? Perhaps both?” This remark came after a reading of the sonata at the office of Jacques Durand, Debussy’s publisher. For some curious reason, a chromatic harpist was employed for the occasion, despite the piece being written for pedal harp. While composing the piece in 1915 and suffering from cancer, Debussy had written to Durand, “all present-day life was far away, harmonious times unfolded, oblivious of the tumult so near, and [the sonata] ended up so beautiful that I almost have to apologise [sic] for it.” It is this earlier statement that is less well-known, but perhaps more accurately describes Debussy’s own love of the piece. There is so much research available to anyone beginning to work on the sonata, that it is easy to learn more than that which is commonly stated in program notes or an online search. So before you dive into the music, spend some time with one of the many books on Debussy and his music. This work came from the end of his life and a stylistic period much different from many previous works. Approaching it with that knowledge can make a big difference.

Choosing an edition

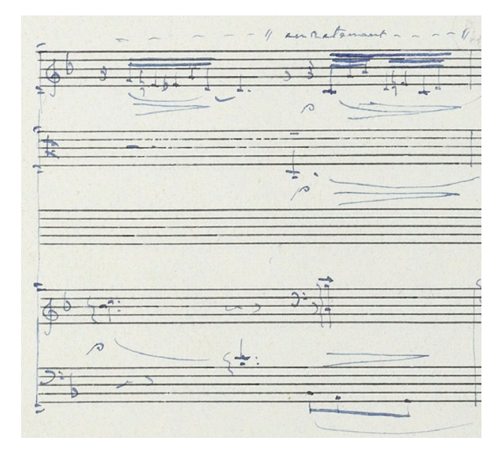

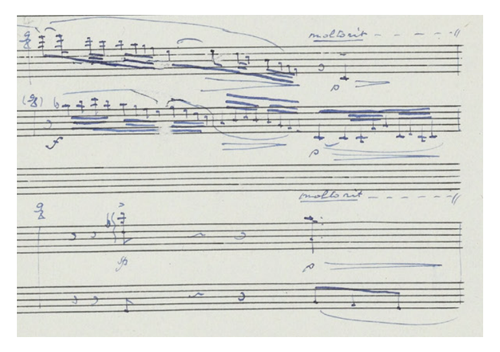

Thanks to modern technology, anyone can access a PDF scan of Debussy’s manuscript online from the Petrucci Music Library (imslp.org). While it would be incredibly challenging, if not impossible, to perform the music from the manuscript alone, being able to see it and study it is a gift to the modern-day musician.

After choosing to tackle this work, the first decision to be made is how to procure music. There are several editions available, and each musician in the trio should purchase their own copy of the score and parts. Often the harpist (who plays off the score) must supply parts to the flutist and violist, but without the score, these musicians are flying blind in rehearsal. Having a score to reference is essential for the other players, as they can more readily see how the parts fit together. They can also easily add cues to their single-line parts to make performance easier. Purchasing a reliable and accurate set of parts should be the responsibility of each member of the ensemble.

There are so many pedal markings to write in and cues needed for the other players, that it is best to have a part that you can keep forever, so you can return to a nicely marked part the next time you play it. While parts are available for download online, do yourself a favor and buy a real part, printed with large, readable notes on heavy paper that will last indefinitely.

For years, the Durand edition was the only option. It was the first print edition of the sonata, and it is still available to purchase. However, the part and the notes have been reduced in size from the original, making it harder to read. There are also several mistakes and some markings in Debussy’s manuscript that did not make it into Durand’s printing. You can find articles about these errors and omissions in the American Harp Journal articles written by Carl Swanson that are available to read in the Journal archives (see Journal issues Winter 2013, Summer 2014, and Summer 2014.)

Swanson’s research into the Durand printing resulted in the creation of his own edition of the sonata, published by Carl Fischer, that incorporates the corrections and missing notations. By consulting the manuscript, he was able to create an authoritative edition that is a great option for any harpist, even one who has played the piece many times before. The music is available in a large size (11 x 14 inches) for easy reading by those of us with aging eyes. In addition to making the corrections and additions, Swanson kept the original format of the Durand score (so page turns are the same for those who are used to the Durand) and included an extensive introduction that includes the history of the sonata, a glossary of French terms, footnotes, and his teacher Pierre Jamet’s experience playing the sonata for Debussy himself. It is an invaluable resource, and I highly recommend this edition.

Swanson’s edition is unapologetically true to the manuscript, with no additional information, such as fingerings or pedal markings. This edition contains both Debussy’s original rehearsal numbers and measure numbers, but curiously, the measure numbers are continuous through all three movements (as opposed to starting at measure 1 at the beginning of each movement). The only drawback to this edition is that Swanson bases his corrections solely on the manuscript and does not include other sources. As a result, there are still a few questions that remain about certain notes and “corrections.”

Aside from the Durand and Fischer printings, another choice is available from Edition Peters (1970). It is edited by Erich List who served as principal flutist for the Gewandhaus Orchestra in Leipzig from 1938–1960. This edition contains facsimile reproductions of the title and dedication pages from Debussy’s first edition, a glossary of the French terms used, and notes from the editor. It is an edition that is based on the first print edition in consultation with the manuscript (autograph) and incorporates corrections that the editor says were made by Debussy to the original print edition. This version does not have the same layout as the Durand, but does make page turns as easy as possible, and it contains pedal markings. The only issue is that the pedal markings might not be in exactly the place you would prefer them, and they are in both letter and solfège forms, which can clutter up the page a bit (each pedal is marked twice, i.e., G# sol#). But if you are learning this without the benefit of a teacher’s or colleague’s pedal markings to reference, this edition can really make life easier.

Often markings are displaced when music engravings are made…and having the original manuscript for consultation can help clear up questions and determine which markings are those of the composer and which are those of the editor.

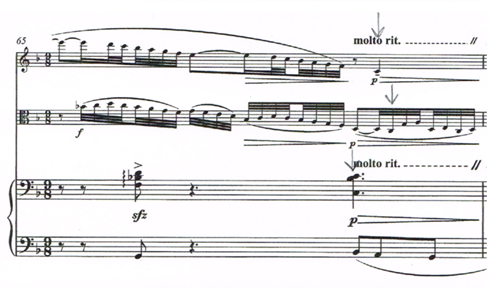

Another helpful inclusion in this edition is measure numbers. However, unlike other available editions, this one eliminates the large rehearsal numbers originally included by Debussy. Obviously, List must have consulted a harpist or harpists when producing this edition, as he added some suggestions for execution, such as “p.d.l.t.” in measure 65 of the first movement for the left hand. Without referencing the autograph, you would not know if that marking was that of Debussy or the editor. While using “pres de la table” is one possible way of executing the passage, it is not Debussy’s direction and will most certainly change the color of the sound produced. (Example 1A: List, mvt. 1, m. 65; Example 1B, autograph, mvt. 1, m. 65) There are also some suggestions for enharmonic respellings and the corresponding pedal markings, which again are not Debussy’s, but many are necessary to play this piece properly. Another example in the first movement is in measure 73, where in the treble clef Debussy writes an E-flat immediately followed by an E-natural. The common way of playing this passage is to use F-flat enharmonically for the E-natural. This edition prints the F-flat instead of the E-natural, so no need to circle the note and remember that you play it on a different string (Example 2: List, mvt. 1, m. 73). These respellings can be very disturbing to purists but can make reading the notes on the page so much easier for anyone new to this work.

There are other suggested enharmonics, such as at the beginning of the third movement. It is common to use B-sharps and E-sharps alternating with the Fs and Cs to eliminate finger noise on the strings and let them ring more, and this Peters edition gives an ossia underneath the first measure showing this use of enharmonics. However, it is not necessarily using them in the most common or obvious way, pairing the E-sharp with C (a sixth) and the F with the B-sharp (a fourth). I play E-sharp and B-sharp followed by F and C, as I would expect most harpists to do. That seems more intuitive, and each hand is playing the same interval of a fifth instead of alternating between a sixth and a fourth. (Example 3: List, mvt. 3, m. 1) This example does illustrate the alternating hands and the use of the enharmonics, though, so to the harpist tackling this piece on their own, it is extremely helpful. There are also fingerings written in throughout—again editorial suggestions, not Debussy’s.

At the very end of the score are the concluding remarks by the editor, which include the corrections made and the sources from which they are taken. Most are from the autograph. It is helpful to see Debussy’s actual manuscript, to see precisely where his dynamic and tempo markings are placed in the music. Often markings are displaced when music engravings are made (even now with computer notation programs this can happen), and having the original manuscript for consultation can help clear up questions and determine which markings are those of the composer and which are those of the editor. Overall, the Peters edition is a legitimate option for performance use, especially if you are preparing this work without the advantage of a teacher or coach to give you markings.

The G. Henle Verlag edition of the sonata (2012, edited by Peter Jost) is another quality choice. This edition does not include enharmonic equivalents or editorial additions, keeping the notation exactly as Debussy wrote it. As such, it is labeled “Urtext” which is meant to indicate that it is the printed version intended to be as close to Debussy’s intention as possible, being the printed version of the autograph with corrections based on scholarly research. (Interestingly, the Peters edition, with its editorial changes and additions, is also labelled “Urtext”). Obviously, the Henle edition lacks pedal markings and fingerings, and its layout differs from the Durand standard. The Henle edition does not do quite as good a job with page turns, but the preface is full of interesting and valuable information about the history of the sonata. The comments at the end of the sonata are also invaluable, as the sources consulted for this edition include Debussy’s sketches, the manuscript, a first published edition, and a copy of the Durand first edition corrected by Debussy himself.

There are many more corrections in the Henle edition than in the Peters, and specific reference is made to each source of correction or change. Because this edition uses more sources for corrections, it attempts to reconcile any discrepancies between the Durand publication and Debussy’s manuscript. By consulting Debussy’s hand-corrected first edition and the posthumous (and presumably corrected) Durand 1920 edition, the editor believes that the Henle edition is the final authority on any corrections.

One last word on the parts: Debussy often gave different dynamic and phrasing marks to the different instruments, even sometimes while they are playing the same or similar notes. Many of the discrepancies addressed by the different editions fix these markings in the flute and viola parts, but I have not addressed them here. Be aware that all three players are not always meant to be playing with the same expressive indications. Play what is on the page and look at the many notes and comments in the editions to be certain of your group’s expressive choices.

Mark it up

After choosing an edition and acquiring the parts, the next step is to put fingerings and other markings into whichever edition you have purchased. Most harpists beginning the study of the sonata are probably working with a private teacher, and that teacher should be the first source of markings. Because these can vary so widely depending on the teacher, it is not the intent here to make judgements on which choices are best. However, it is important to choose fingerings, write them in, and stick to them. Learning any difficult piece of music is made easier by doing this, and the sonata is no exception. Pedal markings are also important and, whenever possible, pedals should be moved rhythmically and consistently. This should not be news to any harpist advanced enough to begin study of the sonata, but certainly cannot be overstated. Hopefully these good habits have already been established by the teacher and will help in any student’s learning process.

As previously mentioned, there are many enharmonics that must also be dealt with, by either circling or rewriting them, and writing in the corresponding pedals. Lastly, if you choose to purchase an edition without measure numbers, write them in to make rehearsing easier later on.

Study strategies

You have your music, you have written in your teacher’s markings, and you are ready to start playing. Where do you begin? Many would say get a recording and listen while watching the score. Almost all the harpists I consulted for this article said an emphatic no to this strategy. While there are most certainly some excellent recordings of the work, there are many that are less than stylistically true or accurate, and, more importantly, this music lends itself to countless interpretations of the nuanced score. Better to learn by playing and create your own conception of the piece before hearing how others feel and play it. If you have done your research, marked your part, and translated Debussy’s interpretive instructions, you should be able to begin playing and discovering your own interpretation. As Eastman School of Music harp professor Kathleen Bride says, the harpist must learn and know the harp part completely before rehearsing with the other musicians.

It is an unfair fact that we have many more notes to play and a larger set of challenges with our instrument. Because we read from the score, we must know all three parts and how they go together so we can guide the other two players who perform from a single line part. This means that we often must begin preparation in advance of our colleagues, but the process of creating the beautiful music of Debussy can be achieved sooner once you get through the mechanics of putting the ensemble together. There has to be a guide for this process, and by default, that role goes to the harpist who always has the advantage of having the score on the music stand. Later, after the piece has time to get “well-baked” (the words of the great harp teacher Leone Paulson), you can listen to good recordings by well-respected musicians and consider the creative and musical choices they have made and how they might differ from your own. While Debussy was meticulous about writing musical directions throughout the piece (sometimes every one or two bars) these can be interpreted differently by every performer. Learn the translations for all the instructions and consider how you want to interpret them within Debussy’s given framework. (See the sidebar for more about recordings that are of historical and musical interest.)

Style

Give it a listen

Recordings of the Debussy Trio by Pierre Jamet, Marie-Claire Jamet, Lily Laskine, and Marcel Grandjany provide interesting historical perspective.

Laskine’s recordings are my favorite. She and her ensembles play at much slower tempi than are often heard today, but that makes the clarity much better and makes it possible to hear all the nuances of color in each player’s performance. Interestingly, Laskine made three recordings—in 1938, 1962, and 1974. The later recordings are actually slower than the first. But in all three, it is easy to hear how the voices fit together, and the ensemble playing is truly wonderful. Unfortunately the recording by Pierre Jamet is dominated by the flutist, who doesn’t seem to be able to count!

Prominent contemporary recordings by the Debussy Trio, Aureole, and Trio Lyra can give the listener an entirely different interpretation.

When listening to live performances, remember that all musicians are human and make mistakes. Listen for overall quality, rather than nitpick. Sometimes you will agree with the musical choices made and sometimes you won’t. Will the choices made by the performers you hear affect your choices the next time you play the sonata?

While notes and rhythms on a page are important to learning a piece of music, even before we start, we need to understand the style of the piece. Especially on the harp, where we have complete control over the sound we make with our fingers on the strings, from the very beginning we must know what kind of sound we are trying to make. It is no different than learning a piece by playing it all at one tempo and dynamic, and then after learning the notes, trying to add expressive elements such as dynamics and rubato. It is hard to add those things after the fact, like adding the flavoring to a cake after it is baked. (Another baking metaphor!) Debussy’s style of composition is often called “impressionistic,” likening it to the Impressionist school of art that was made famous by painters such as Monet and Degas. While Debussy may have shunned this label, his use of color and nuance make him a “Painter in Sound,” just as Stephen Walsh titled his biography of the composer. Walsh describes the sonata, writing, “The mood is unforced, and the form open and somewhat improvisatory. Frequent tempo changes create an easy, almost opportunistic atmosphere, constrained by formal reprises at crucial moments: the sonata form moments in the first movement, ‘Pastorale,’ the rondo moments in the ‘Interlude,’ and the cyclic, back-to-the-first-movement moment near the end of the ‘Finale.’” Walsh goes on to call the music “elegant” and “wistful,” and the texture is mostly transparent and flowing, with all three instruments moving frequently between solo prominence and ensemble coherence. Sometimes melody is passed from one instrument to another, and at other times they meld together creating an altogether new sound. Debussy calls these last three works sonatas, which implies a form used for centuries. But he creates a meandering, loose form that gives the listener the illusion of improvisation. This mood is crucial to the style of the piece and is as important as learning the notes and dynamics.

Rhythm

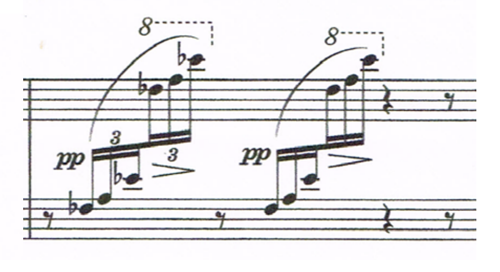

With that being said, rhythm cannot be improvisatory from the beginning. Instead, it is crucially important to read and learn the correct rhythms before attempting rubato and “improvisatory” interpretation. The intricate rhythms that Debussy wrote are specific and detailed, and interaction between the instruments is carefully planned no matter how improvisatory sounding the overall effect may be. There is no reason why each rhythmic gesture, no matter how complicated, should not be executed with the same precision that Debussy used in writing it. Once the correct notes can be played in the correct rhythms, the rubato and tempo changes indicated by Debussy can be employed to much greater success than when there is questionable rhythm to begin with. One of the most important and yet neglected techniques for playing correct rhythms is counting internally. If all members of the ensemble feel the inner pulse and count (especially through long notes or rests) everyone will be able to stay together and create organic rubatos, accelerandos and ritardandos where indicated. It is also important to subdivide and figure out exactly how difficult rhythms should be played by counting through them. There are several examples, many in the first movement, where the music is rhythmically challenging and, as a result, is often performed incorrectly (Example 4: mvt. 1, m. 14–20; Example 5: mvt. 1, m. 52–53; Example 6: mvt. 1, m. 70). The employment of a metronome, subdivision, and slow practice are always helpful, both alone and with the ensemble. You must be completely comfortable at slower tempi before attempting to play at performance tempo, especially in the second and third movements. Clarity is key in the third movement, so the tempo should not be faster than the listener can discern the eighth- and sixteenth-note triplets in the opening motive played by the flute in measures four and five (Example 7: flute part, mvt. 3, m. 4–5). This theme returns in the other instruments and at the very end of the movement and should not be so fast as to be a blur of sound. In general, this music works best when it is clear and transparent, and if that means slower tempi, who’s to say that is wrong? Marcia Dickstein, harpist for 33 years with her chamber group, the Debussy Trio, says she used to believe there was a right and a wrong way, but now she is more flexible. To play well and correctly and with the nuanced musical colors that Debussy wrote is far more important than a fast tempo.

Melody, harmony, and voicing

Example 4: mvt. 1, m. 14–20

Example 5: mvt. 1, m. 52–53

Example 6: mvt. 1, m. 70

Example 7: flute part, mvt. 3, m. 4–5

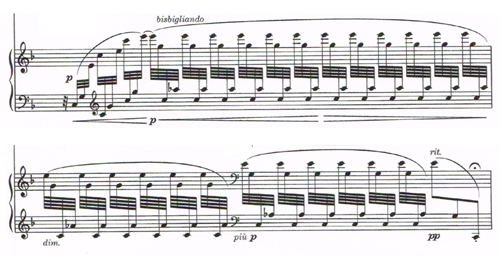

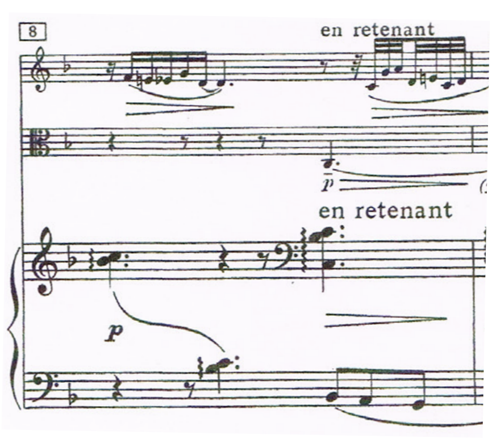

Example 8: mvt. 2, m. 22–25

Example 9: mvt. 3, m. 16–18

Debussy’s harmonic language is uniquely his, and in the sonata, there are key centers without traditional scales and chord progressions. Different modes are evident, as is the pentatonic scale, a favorite of the composer. It is important to be aware of key centers and changes of harmony, but as with most other elements of music, Debussy did not employ them in a conventional way. Identifying and recognizing the key centers and how they modulate can be immensely helpful when learning this sonata.

Melody can be long, extended, and passed between instruments, meandering through the first movement especially. It is always important in ensemble playing to know when your part should be more prominent and when it is accompanimental, meant to be more in the background texture. Identifying melodic elements and gestures and studying the score will help a player to know when to be in the forefront and when to be supportive of the other instruments’ moments of melodic prominence. Deciding which “voice” should be brought out at any given time is an important part of the many decisions that must be made as an ensemble. However, Debussy’s intentions can be studied in the score before you get to that first rehearsal. Then, as a group, decisions and compromises can be made, and then incorporated into the performance. As harpists we must deal with voicing issues frequently, since we play all the parts of our piece by ourselves. Consider the Handel Concerto or Bach counterpoint—we decide for ourselves which voice is prominent at what time, and we can control completely the effect of a piece by doing so. In this ensemble we must be flexible and consider the opinions of the other players, creating a truly collaborative environment. Stacey Shames of the Aureole Trio says she believes that “the blending of the voices is as important as their differentiation.” It is true that sometimes the notes blend together to form a new color, and at other times each of the instruments is heard as an individual part of the texture.

Tempo

One of the most challenging decisions for the group is settling on a tempo for each movement, since Debussy did not give metronome markings. The first movement, titled Pastorale and marked Lento, dolce rubato, is usually played around 94–100 to the eighth note. Anywhere in that neighborhood is desirable, and most often there is agreement among all the musicians on this tempo. At this speed, the clarity of the lines and rhythms is easily heard by the listener, and the relaxed, pastoral mood is effortlessly created. The second and third movements are more problematic, often being played too fast.

Movement 2 (Interlude) has the marking Tempo di Minuetto, but Swanson, in both his article and his edition of the sonata, tells a story of how his teacher, Pierre Jamet, played the sonata for Debussy. After commenting that they were playing the movement too fast, Debussy added the words grave et lent (solemnly and slowly) to the tempo indication. Jamet gave the metronome marking 63 to the quarter note to his students, either getting that directly from Debussy or establishing it from memory and his metronome after his rehearsal with Debussy. Either way, the slower pace makes more sense when looking at the harp solo that starts in the ninth bar after rehearsal figure 7 (Example 8: mvt. 2, m. 22–25). This solo is marked au Mouvement and graziosamente. This indication means that the harp is to return to the opening tempo and play this lovely passage gracefully. If it is too fast, it will sound frantic and messy, not graceful. Therefore, the tempo of the entire movement can be determined by this solo harp passage. It is necessary to bring out the melodic notes in the right hand that Debussy indicates with tenuto marks and dotted eighth and sixteenth downward stems, so playing this movement too fast will make that problematic. There are multiple places in the movement that are marked animato or animare, and if you start too fast, it will be hard to go faster without losing the Minuetto feel (and without sounding rushed, chaotic, and sloppy).

Once again, the clarity and subtlety of Debussy’s writing is dependent upon detailed execution of all his indications, and if playing too fast, all those details are easily lost. In addition, if this movement is too fast, it will make the final movement less dramatic and exciting. The difference in the tempos of the second and third movements should be a marked one.

The third movement, “Finale,” is marked Allegro moderato ma risoluto. Once again, if you start too fast, you have nowhere to go later in the movement when Debussy indicates to gradually go faster or to make an outright accelerando. The beginning figure in the harp and viola is meant to imitate a tambourin, a French folk drum most often played with a small recorder. Therefore, the opening of this movement is meant to have a percussive quality, fast and rhythmic, yet not too fast, as once again, the harp solo coming up should dictate the tempo. At rehearsal figure 16, the harp plays the motive played by the flute in measure 4 of the movement (Example 9: mvt. 3, m. 16–18). The harp must play this passage in a low register and with a diminuendo, so this movement should be started only as fast as the harpist can play it cleanly and clearly (it is the only melodic and motivic element at this point). Even though this movement is allegro, it should be, as Debussy says, “moderate” and “resolute,” not frantic, and you need to leave room to get faster later in the movement.

As mentioned before, it is imperative to really know this piece before meeting the other musicians for rehearsal. Practicing slowly, deciphering difficult rhythms, counting, working with the metronome, subdividing, and lots of practice will help. Practice in sections, but then practice the transitions so each movement sounds like one cohesive unit, and the sections flow together seamlessly. All of these strategies can be employed by the ensemble in rehearsal, including playing the dynamics, articulations, and phrasings from the beginning. The challenge will be to move from playing strictly in tempo (necessary in the beginning) to applying the rubato and tempo changes that Debussy indicates. Especially in the first movement, all these changes need to flow together, and they can be achieved if all the musicians are feeling the beats and subdivisions of the beats together. Don’t be afraid to count out loud in rehearsal and use subdivisions of the beat to help your tempos change gradually and organically, not abruptly (unless indicated, of course). As a group, slow practice can be helpful in difficult passages, as can playing strictly in tempo with a metronome to make sure everyone is playing correctly before applying tempo changes or rubato.

Other considerations

Example 10: mvt. 3, m. 95

Example 11: mvt. 3, m. 109–110

As you begin rehearsals, it’s important to consider your ensemble’s sound. The sound called for here is not the sound of the orchestral flutist or harpist who needs to fill a 2,000-seat hall with the Nutcracker cadenza or the opening of Afternoon of a Faun or even the Mozart Concerto. This piece calls for a chamber music sound, with more nuanced color and many more dynamic levels. Kathleen Bride says this can be the biggest piece in the puzzle, asking the musicians to forgo their “orchestral” sound and attempt something less “in your face.” “It is all about ensemble playing, all about sound,” she says. Barbara Allen, founding harpist of the Aureole Trio stresses “the importance of the fluid lines passing between the instruments and the importance of knowing everyone’s part.” It is crucial that each player knows what the others are doing, so everyone should have their own score and (except for the flutist) be able to sing the other players’ parts while playing their own, especially the melody when their part is the accompaniment.

It is also important to remember that, while each movement has its own separate title, tempo, and character, this is a cohesive work that needs to feel unified, not like three separate pieces. The third movement brings back elements of the first two, giving the listener a glimpse into the immediate past, so there has to be some overall cohesion to the sonata, even with the varying tempi and moods. There is a brief reminiscence in movement three of the graceful harp solo from movement two (three bars before rehearsal 22) and an actual return to movement one at rehearsal 23 (Example 10: mvt. 3, m. 95; Example 11: mvt. 3, m. 109–110).

The sonata is in the French tradition of a suite, with the returning themes and the names and tempos of the movements harkening back to the time of Rameau. Once again, Debussy rejects the later classicism of the Viennese School and claims his French heritage, declaring it on the title page and in the form of his music. (See History Buff below.)

Practical matters

There are other choices that your ensemble must make, like how to set up and whether everyone will sit or the flutist and violist will stand. Sometimes these decisions must be made based on your rehearsal or performance space, but often it is just a matter of being comfortable and being able to hear and see each other. In performance you will need to make eye contact when starting and finishing movements, or when instruments need to play together, so make sure you are rehearsing in the same setup you will use for performance. Decisions will be made throughout the rehearsal process about who will lead where, how to start each movement, and how each movement will end, and that “choreography” needs to be carefully rehearsed as much as the notes. Bride suggests that the violist be in the center, with the flute on his or her right, and the harp on the left (angled towards the audience, not pointing across the stage). That way the harpist can make eye contact with both musicians through the strings (see diagram below).

As far as standing or sitting, it is a choice you all must make as an ensemble. Be comfortable and be able to hear and see each other. There is no right way to set up. Just make sure you make those decisions early on and rehearse that way, so when performance time comes you are not unnerved by a new setup or the inability to make eye contact with the violist to start that last movement.

Not only is the Debussy Trio a rewarding work to learn and play, but it is also wonderful to share it in performance. The harpists I talked to for this article all say they learn something new every time they play it, even with some having hundreds of performances under their belts. The music can be different each time it is performed if it is approached in a thoughtful and informed way. Sharing knowledge about the piece through original program notes or a spoken introduction can help audience members to understand, appreciate, and enjoy the music more, especially those to whom the work is new. If you know the history behind the music you play, and learn about the composer’s intent, you can create more meaningful, confident, and beautiful performances.

For the musician, though, it is the journey of learning and rehearsing this piece that is the true gift. As the legendary harpist Sarah Bullen wrote in my lesson book years ago, “the way is everything, the goal is nothing.” It is the journey; the hours, days, weeks, months, and years we spend with this piece that are the most rewarding. An individual performance can be great or not so great, but this is a piece you will come back to time after time and with each visit rediscover the joy of this amazing and powerful work. •

Correcting the “incorrect” correction

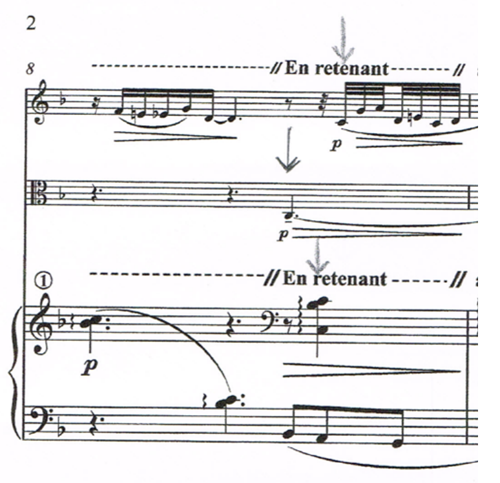

There is one problematic measure in the first movement that needs special attention—measure 8. In the eighth measure of the first movement, on beats 7–9, the manuscript of the sonata clearly shows the right hand harp chord being played on beat 8 (Figure 1: manuscript, m. 8). Yet in the published edition, this chord is written on beat 7 (Figure 2: Durand, m. 8).

Figure 1: manuscript, mvt. 1, m. 8

Figure 2: Durand, mvt. 1, m. 8

Measure 65 of this movement has the same musical material, again on beats 7–9, but with the instruments changing parts (Figure 3: manuscript m. 65; Figure 4: Durand, m. 65).

Figure 3: manuscript, mvt. 1, m. 65

Figure 4: Durand, mvt. 1, m. 65

We have to assume that the publisher “fixed” the harp part in measure 8 to match measure 65. However, if you look at the three upper voices (flute, viola, harp right hand) independent from the bass line (harp left hand), in measure 65, the harp plays on beat 7, the flute on beat 8 and the viola plays off the flute with the 32nd note figure. If Debussy was reassigning these parts using measure 8 of the autograph as his model, one of the voices should be playing on beat 8, just before the flute plays the 32nd-note motif, and that is what he did. Without being able to examine the other sources cited by the Peters and Henle Verlag editors, it is impossible to know how this correction was made to the original Durand printing, and both of these newer editions maintain the measure as Durand printed it (Figure 5: Peters, m. 8; Figure 6: Henle, m. 8).

Figure 5: Peters, mvt. 1, m. 8

Figure 6: Henle, mvt. 1, m. 8

But in my opinion, by analyzing the three upper voices in both measures and consulting the manuscript, the harp chord in measure 8 should be played on beat 8, as it is printed in the Swanson edition (Figure 7: Swanson, m. 8; Figure 8: Swanson, m. 65).

Figure 7: Swanson, mvt. 1, m. 8

Figure 8: Swanson, mvt. 1, m. 65

History buff

As mentioned earlier, another important part of learning any piece of music is finding out about the time and circumstances in which it was written. The sonata was written in the fall of 1915 and was one of the last pieces Debussy wrote before he died of cancer. World War I was raging, and on the title page of the printed edition of this and the other two completed sonatas were the words “Composées par Claude Debussy, Musicien Français.”

Despite Debussy’s expressed love of Wagner’s music earlier in his life, by this time no French musician wanted to be associated with or mistaken for a German. But this label also implies Debussy’s use of certain French musical qualities and harkens back to the French music of the 17th and 18th centuries, and as Debussy himself said “a very ancient Debussy—the one of the Nocturnes it seems?” At a time when Debussy was aware of his illness and impending mortality, yet having a fruitful compositional year, he moved forward but with retrospection in his musical style.

All these circumstances can and should be considered when studying this work. There are many available articles and books written about Debussy’s life, and even volumes of Debussy’s own letters and writings that can give the performer insight into the mind of the composer at the time these three sonatas were written. Such knowledge can completely change your own perception of a piece, and, when working on a monumental work such as this, we owe it to ourselves to take the time to do the research and the reading.

Another historical consideration is the instrument of the time. The pedal harp available for performance would most certainly have been the Erard double-action harp. This instrument was considerably smaller than the concert grand harp most of us play today, with lighter tension on the strings and most likely a straight soundboard. Consider the differences that the instrument would have had on a performance, and make necessary adjustments, such as playing the bass clef notes lower on the strings for more clarity, or moving up or down on the gut strings to vary tone color.

There are also possibilities for employing enharmonics, to make the harp more or less resonant, depending on the desired effect. By using sharps as enharmonic substitutes for flats, you can eliminate some resonance to enhance clarity and transparency in the sound. Often teachers pass along these markings along with fingerings and pedals. Ask why! Don’t just copy them in and play without knowing why these choices were made. It can be a fascinating part of learning the harp tradition that has been passed down for generations from the Paris Conservatory. •