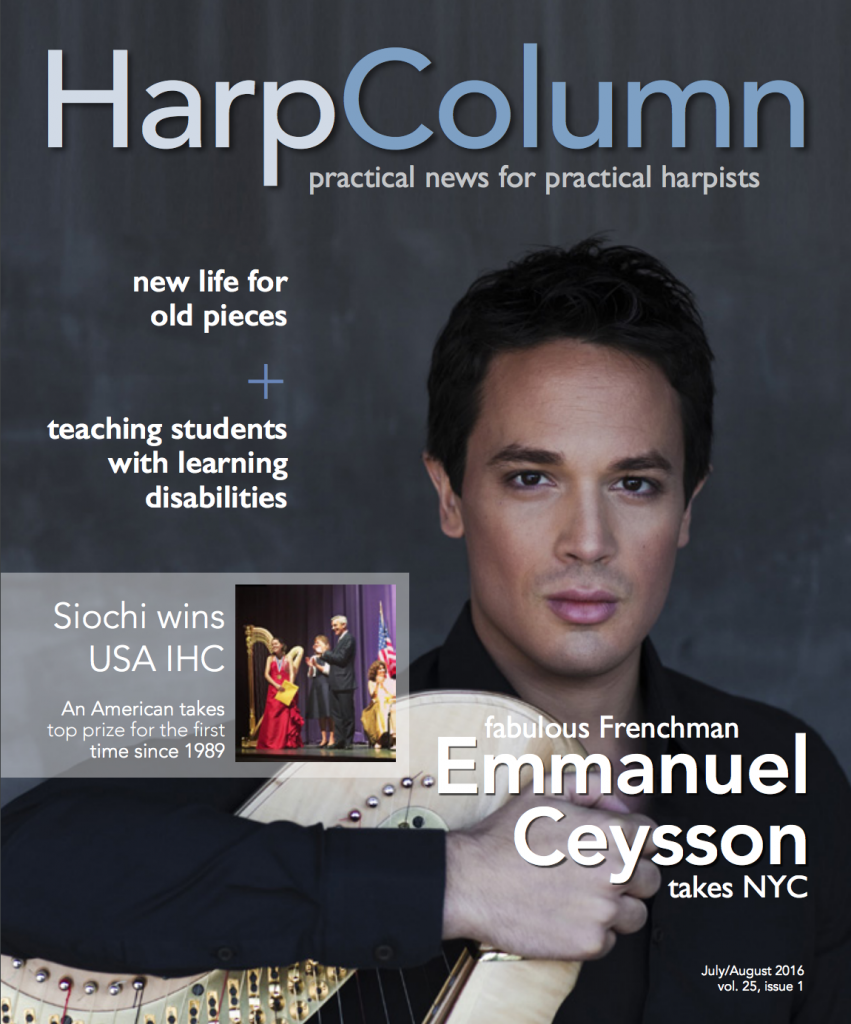

—by Elizabeth Hainen

Deep in the pit of the Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center in New York City, Emmanuel Ceysson says he feels right at home. It might be thousands of miles from his last job at the Paris Opera, an ocean away from his French homeland, but Ceysson says everything about the city and the Met suits him. Evidently he suits the Met as well, as United States’ premier opera house extended tenure to him this spring, after less than one full season on the job.

We asked Ceysson’s colleague Elizabeth Hainen, principal harpist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, to sit down for a conversation with Ceysson during the Philadelphia Orchestra’s trip to New York in May to perform at Carnegie Hall. We think it’s safe to say Ceysson is settling in quite well.

Harp Column: Congratulations—you just finished your first whole season with the Met and you just received your tenure, right?

Emmanuel Ceysson: Yes, yes.

HC: What is that [tenure] process like with the Met?

EC: Usually, tenure at the Met happens after two seasons, two complete seasons with the orchestra. But in some particular cases, like mine, they allow early tenure, and that is what happened. Basically, I had my job at the Paris Opera and had been on a leave of absence for a year, which is called a sabbatical. [That means] if I wanted, I could go back to Paris next season. [The Met] obviously didn’t want that, so I met with [Met Music Director] James Levine two weeks ago, just before the last show of Simon Boccanegra, and he told me that I got tenure. It’s perfect because I always wanted to stay here, that was never a question, but I wanted be sure I got a job as stable as I had in Paris.

HC: Right, and also because you were a seasoned professional, it really makes this process much easier to discern.

EC: Yes, I mean it is very funny because even coming from my colleagues at the Met, they have been telling me—from the first recital up until now, in September—it was clear to us that you were going to stay and that you were perfectly up to the standards for the Met. They were not worried; I was, because I always doubt myself. But the season was amazing! I had a great time. I have been in an opera house for nine years, so I have played a lot of the repertoire, but this year I learned like six new operas. Fortunately everything went well; I know the job, and I know how to be an opera house harpist.

HC: That’s what I was going to ask you. What were the highlights from this year for you?

EC: Well, there were two highlights just when I started the year. The first rehearsal was with Yannick [Nézet-Séguin] on Otello. Even if the part is not big, it is very exposed. It was my first time with Yannick, my first rehearsal with the Met orchestra, and it was definitely something I will never forget. I really had an amazing time. And then the second week of rehearsals we started with James on Tannhäuser, which is a part that I had played before, but it’s one of the most challenging parts. And so I insisted on being alone. Usually you double the part so that you can get everything done, but I had a long solo and it was alright. It was actually one of the first operas I played in a pit in my life. I think I was 21 or 22 when I first played it. It was before I won in Bloomington actually, I think; and with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, and I played it alone at that time, so I’ve been doing it that way since. So Tannhäuser with James was definitely one of the highlights. Then I loved playing Turandot. I love Puccini operas, and Turandot is a Met production that I have always admired a lot. The production itself from [Franco] Zeffirelli is very classical, full of gold. And the harp part, even if it’s not that interesting, it was just such a pleasure to play Turandot this year. I just really loved it.

HC: When I was at the Kennedy Center, my first position was playing the opera, Turandot was the highlight for me as well. Tell me a little bit about how you experience the difference between playing symphonic literature on stage versus opera literature in the pit. What are some of those challenges or advantages might for you?

EC: It’s very different. I love symphonic repertoire also, it is very interesting for me, but I actually happen to think that playing symphonic repertoire is a bit more challenging in many ways. First of all, because you change repertoire every week there is something new on your stands to play every week, which is not the same with opera. Opera, you go for a run. It’s going to go for eight or nine shows, and it is going to go through one or two months. So that’s the first difference. Then the second thing is that you only get one or two concerts [in an orchestra], but in the opera you experience a progression. Throughout the shows you find new things to do and musically evolve. So for me I feel more comfortable being in opera than being on stage, being in the pit, I mean, part of an orchestra, I think I like being in the pit more for several reasons. The first reason is that you don’t really need the exposure when you’re in orchestra, I mean, it’s not what you’re looking for. Definitely not. You are part of a bigger thing, a bigger picture, so being in the pit is kind of less pressure, I think, than being on stage. Then, the conductor has a different role when he conducts opera than when he conducts symphonic music. They can be less a pain when they are conducting opera, because they have to take care of the singers, and so they leave us more free in our choices. They give us a little bigger margin musically, I would say, than in symphonic music where you sometimes get control freaks, and that I never liked. I like to feel free. For me, playing in the [Met] orchestra is like a big chamber music session, basically. You hear your colleagues, you adapt to the singers, but the conductor has a much less important role. I don’t like to be too “conducted.” [Laughs] That’s why I’d rather play, I think, in opera. And then also I get my share of stage, during the season, because I play all my solo stuff, so it’s not like I don’t play on stage.

HC: Right. And how many times does the Met play on stage as well? Because you do have some special concerts throughout the year.

EC: Usually we have concerts during the season, but now they regrouped all the symphony concerts at the end. Our music director just stepped down. A new music director will be named soon, but he is not going to be there for five years. Hopefully the new director will want to do symphony concerts during the season, or even tours; I would like that very much.

HC: I know that Yannick, our music director, is one of the conductors that has been considered.

EC: Yes, I guess it was a rumor. We don’t know anything, because it just happened, and the process is going to be very long. I think we will be consulted as an orchestra, as orchestra members,. I love Yannick, and I love working with him. And also he speaks French! [Laughs] So that makes me feel even closer to home! But yeah, it would be amazing if Yannick would come. [Editor’s Note—on June 2, several weeks after this interview, the Met announced that conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin will be its new Music Director. Nézet-Séguin will continue in his current position as Music Director of the Philadelphia Orchestra in addition to his Met responsibilities, which he won’t fully assume until the 2020-21 season.]

HC: Now, let’s talk a little bit about your arrival in New York from Paris. It hearkened back to the time when Salzedo came to the Met to play for Toscanini.

EC: It’s very funny. I feel like I’m in the tracks of Salzedo, I mean, I also play the Salzedo harp. I have a huge respect for Carlos because I love that he was not only a harpist, but I happen to see him as a visionary, like someone that had a vision not only for the harp but for the music. He composed a lot, he always wanted to promote the harp as much as he could. He liked new music, he wrote books for tutoring new composers so that they could know the instrument better. He was also a pianist, and he was all over the place.

HC: He was also an impresario, even selling tickets for the concerts. At times he was doing everything! [Laughs]

EC: Yes, he was doing everything. I think that he’s the kind of person that we need today in the harp world to represent our instrument, you know, because it’s still mistreated. It’s a very sad truth, but it is, and yes, I want to build up the harp as much as I can. I didn’t have much time this year because I had to settle in New York, you know, getting everything together, but starting next year I have big recording projects coming up over the next two seasons, in France and also here in the U.S. Salzedo will be the theme of one of my next CDs.

HC: Will it be his solo repertoire?

EC: No, it’s going to be a mix of repertoire from different composers. Some of the program will be French repertoire which Salzedo used to showcase European composers to the International Composers Guild when he first arrived in the U.S. There will also be other music from the same period, and of course some of Salzedo’s own works. I will record the whole CD on the red Salzedo [model Lyon & Healy harp], so there will be a theme on the color red too.

HC: And why the color red?

EC: This harp, the red harp, was built for the 150th anniversary of Lyon & Healy. I think I was the first one to play it in concerts, and I loved the instrument. As soon as I played it I was like,”I am going to buy this harp.” You know how they picked the color? Do you know the story?

HC: No, not really.

EC: It was the color [Salzedo] used to correct his scores, or the scores of his students, so basically Lyon & Healy asked some of Salzedo’s students to send their scores corrected by him and they took the same red he used and they built a harp based on this red color. And we got red harps for the Met too. It was one of the big highlights of the year. I found a donor to give the money, and she wanted the harps to be red. She was the one that asked, actually. It’s funny because she saw one of the videos I had on YouTube, the one in which I played Colorado Trail, I think, with the Tabernacle Choir in Utah. And she said, “Oh, I love this instrument! It is so you. It is so sparkling. I really want these harps to be red.” And I said, “Well, please first ask the general manager of the Met if it is going to be okay.” [Laughs] And she said, “I won’t have it any other way.” And I said, “Okay, okay. We’ll get red harps then!” [Laughs]

HC: It’s kind of nice that it will stand out more from the pit. So, I want to ask you, because I think it really is important in my generation and in your generation, do you see yourself in the role of a teacher more in the future as well concertizing and recording?

EC: Yes, I think so. I think that there are three pillars in a harpist’s career. There is playing alone as a soloist, which is the first pillar for me. It is the one that has been holding me up since I was a little boy, and I picked the harp. I wanted to be a solo harpist. It was what mattered to me. The second one is playing together, which means chamber music, orchestra playing—learning to interact with other musicians and integrating the harp in a bigger picture. And my third pillar is transmitting, teaching. I think there is one simple reason for this. When you have a student in front of you, you have to make his problem yours and understand when he has a problem like a technical difficulty that he cannot pass, you have to try to understand how he is different from you and why is he having this problem and then how can you help or guide him through the resolution of this problem. It can be difficult. The problem could be a musical one, or it can be personal, because everything interacts when you’re a musician and an artist, I think. So I always needed to teach, and actually it was kind of sad for me to leave Paris because I just got the position at the École Normale, and I had a class there. I loved it, but I’m sure I’m going to find a studio in New York or in the area soon enough.

HC: I’m sure you will. So, many of us love New York City, as Americans, but we love to go to Paris and we love Paris as well. So these two cities, obviously you love them both, but what is it about New York that you find fascinating?

EC: Well, to begin with, the Met was a dream for a very long time. I mean, I grew up listening to operas and recordings from the Met opera. The first recital that I ever saw was the one James did with the Met and the Deutsche Grammophon on DVD. I have it here at home actually. The Met was, for me, the perfect example of the perfect opera house. I mean it’s like your repertoire opera house so you have a lot of variety and you move around a lot so you don’t get bored, which was one of my problems in Paris. Then, of course, I love the city of New York. I have been coming here for a while because I won the [Young Concert Artists] auditions in 2006. Since then I’ve been coming back almost every year, not to play in New York, but it was always my first base. I was always landing here and then flying in the U.S. from this hub. And so I have friends here, people who have hosted me—my New York family I call them. I came here a lot, but coming here for a week and coming here to live is something different. And then also living in Paris is something different. I actually didn’t like living in Paris so much. I appreciate it very much when I come back for a visit to see my family or my friends because it’s only a week or two. But everything that Paris is known to tourists for—the “city of light,” the “city of romance”—are things that you experience when you have a lot of time to go out. When you live in Paris, the romance and the magic kind of go away. I mean, it’s a very beautiful city, but it is more boring than New York and it was not matching my personality as much as New York is now, because New York is so lively. You have shows every night. You have Broadway, which I love. You have many museums in Paris too, but something happens all the time in New York. There is a rhythm that matches my personality and my age right now. I am not sure it is still going to match 20 years from now, but at the moment it is what I need.

HC: I think that is really well said. I love New York too. For music, it was a place that many of us as artists hope to live for some part of our lives and spend time. So tell me a little bit about your regime as a health conscious person. Because I know for me, I need to live my life in a healthy way in order to play my harp in a healthy way. And so I’m an avid yoga practitioner, and I know that you are very conscious about your health as well.

EC: Yes, it was already very important in Paris, but as soon as I arrived here, I realized that as we play many more shows this year than I used to play in Paris, I work a lot more here. It’s very crazy in terms of workload. I need to be much more conscious and careful with my habits. Also I was a little afraid because Americans have this bad reputation of junk food and eating unhealthy and having agriculture that is led by big firms like Monsanto or things like this, or eating GMOs, so I was very afraid of that. That made me even more conscious of my eating habits here. I try to eat organic as much as I can. I don’t do well with junk food at all, and then I exercise a lot actually. I have never been in as good shape as I am now. I started a new program, so I feel much stronger now. I work out; I hit the gym five times a week. I try to run or to swim as a cardio exercise. I just turned 32 like a month ago and I’ve never felt better in my body.

HC: That’s great. I think it’s so important for other younger harpists to hear this, because I think, for a long time, we didn’t acknowledge the physicality of the instrument. It takes a tremendous amount of strength, not just to play it but to move it, as we all know. You really need to be very conscious of the way your skeleton is stacked up and the instrument and everything, you know. And certainly with teaching, you need to guide students this way.

EC: Yes, it’s very important, and also in eating too, because we are what we eat. It’s not a false statement, and the body, especially the back, it’s one of the parts I insist the most on in my gym routines, the lower back and the back muscles because they have a tendency to get pulled, I mean, we put a lot of tension on those, and shoulders too. Harpists don’t mind their shoulders most of the time. The first thing is to get conscious of this part of your body when you play and then to be able to work on them to have them function the best way and the longest as possible.

HC: Wrapping up, you have been the prizewinner of several international competitions and well as holding principal harp posts with the Paris Opera and now with the Met, which is the finest opera company in the world. What advice would you give to young harpists who yearn for these prizes and hope to compete?

EC: I have evolved a lot on this question. I have been a fierce competitor for a very long time, and I realized a few years ago that I am much more calm now with this in my life. I was not competing with others, but I was competing with myself. In France, this is the way we are taught, to always doubt ourselves. We are usually unsatisfied. We always see the glass half empty. It can be good motivation, always pushing you to become better, but at some point in life it also becomes destructive. It took me years and several competitions to realize that, because I always thought that competition would open the door to a huge international career as a soloist. As much as we would like to believe in this dream, it’s not very true, unfortunately. [Laughs] It’s not politically correct to say that. But I also think it does not mean that it’s not good to take part in the competitions, you just need to take them for the good reasons. Winning an international competition, you are going to be respected in the harp world and that’s very good, but it’s not going to change your life as a musician. The reason you should do competitions, because I do still think that they are important, is as a personal challenge, I think. It’s a way to overcome your personal fears and flaws. I think working on those should be the main point of competing. Of course you want to be the best and to win, but don’t expect too much of the “win” because you might be disappointed. •