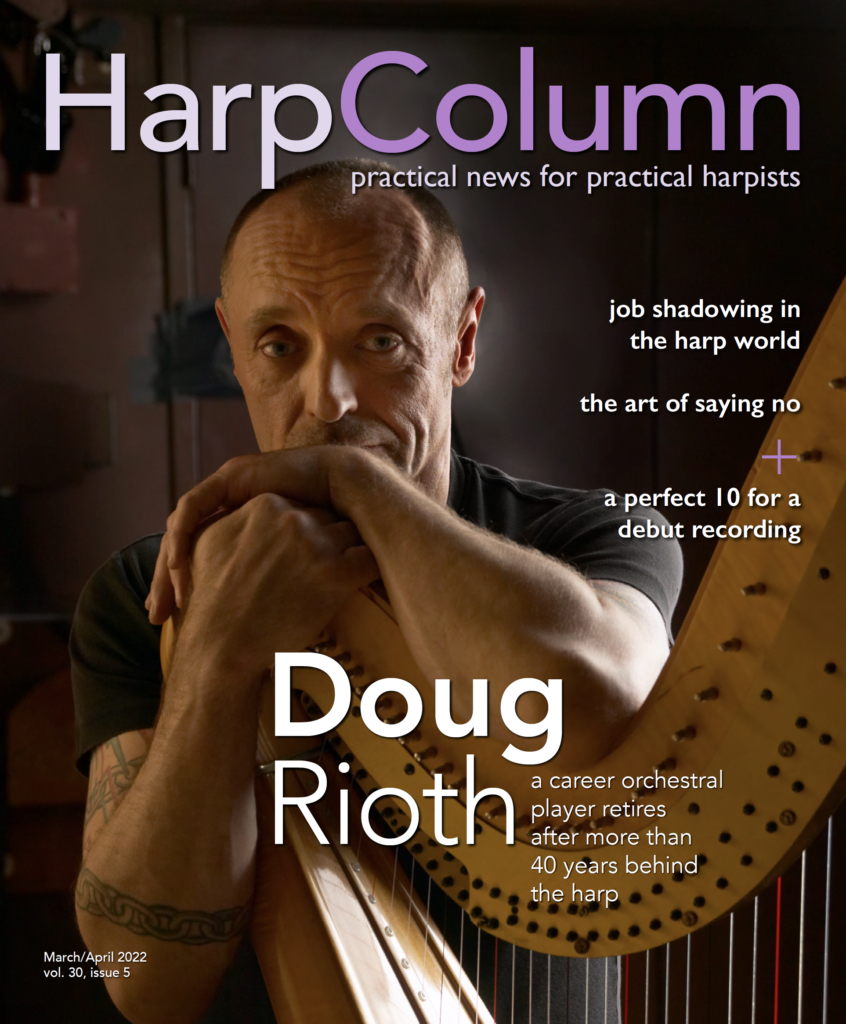

Although Doug Rioth and I were not classmates at our mutual alma mater, the Cleveland Institute of Music, we have many things in common, beginning with a mutual admiration for our beloved teacher, Alice Chalifoux. We knew each other from our summers in Maine at the Salzedo School and from my trips back to Cleveland after I joined the Pittsburgh Symphony. When Doug was a junior in college, he came to Pittsburgh to play second harp with me in Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms. We became close friends after the death of Miss Chalifoux in 2008. We talk at least once a week, and invariably one of us quotes her or mentions a funny story involving her.

We also share a love of teaching and educating students about the Salzedo method. I have had several of Doug’s students come to the Shepherd School at Rice University or to summer music festivals where I teach. I am always delighted by his students and the excellent training they received from Doug. Dialogue about how Miss Chalifoux taught and our continuation of the tradition is always a part of our phone conversations. When I retired from the Houston Symphony, Doug came to play Mahler 8 with me in my final concerts, and I returned the favor this past December, joining him on Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune and La Mer in his final two harp subscription concerts with the San Francisco Symphony. It felt as if we had come full circle from the Bernstein concert 40 years ago.

I will miss my colleagues and the wonderful sensation of hearing great music day after day, week after week. It was a gift to have such a career.

Harp Column: I want to start by saying congratulations on your retirement from the San Francisco Symphony and on your fabulous career.

Doug Rioth: Well, thank you. And I want to thank you for coming and helping me celebrate my last weeks of subscription concerts by playing second harp with me.

HC: It was really fun. We had a great time. It was a great memory.

DR: Yes.

HC: My first question is how were you introduced to the harp? What triggered your decision to pursue harp performance?

DR: Well, I was a piano student from the time I was six, and then I started the bassoon in high school band. My band teacher suggested I go to the National Music Camp at Interlochen for a summer camp experience. I went and was in the orchestra and noticed the harps. There were four harps in the orchestra, and I had never seen a harp growing up on a farm in Missouri. I was just fascinated by what they looked like and the sound they made. It was a very unique sound to me, and I was also fascinated in particular by one of the harpists, Katie Kirkpatrick, who I’ve remained close to. She is a long-time, prominent studio harpist in L.A., played second harp in the L.A. Phil quite often, and has come up and played second harp with me also. So I started taking harp lessons and went to the Interlochen Arts Academy for two years of high school. During those two years, I switched from a piano major to a harp major. My first year I was a piano major, my second year I was a harp major. I realized I could probably make a living on the harp easier than on a piano. Lots of people play the piano; not so many people play the harp. It was a good decision. I didn’t make very many good decisions when I was a teenager, but that was one of them.

HC: How did it come about that you were able to study with Alice Chalifoux?

DR: Well, my harp teacher at Interlochen was Lisa Smith Dicken, and she was a student of Alice Chalifoux’s and had studied also with Salzedo. So it was natural that Miss Chalifoux came up to Interlochen and did a masterclass. She was incredibly impressive. I recall most of my class was spent on the first page of the Pierné Impromptu-Caprice. Such intense work on one page or even the first line was very enlightening to me. She seemed to be the teacher. No questions after that. I wanted to go study with her.

HC: I know that you attribute much of your success to her teaching.

DR: I do.

HC: What was it about her teaching that made her such an outstanding teacher?

DR: She wouldn’t give up in lessons. She was insistent that we repeat and do it over and over until it was right or as close to right as possible. Her beautiful sound and expressive way of playing was very moving to me. I would go to the Cleveland Orchestra concerts week after week to listen to and watch her—I just wanted to be able to play like that. It was something I’ve never experienced. I’ve never heard anything like it. And I still never have. I hear a great many orchestras, but I have never heard anyone play in an orchestra or come even close to what I heard from her and the Cleveland Orchestra.

HC: Is there one musical attribute that you consider most important for success as an orchestral musician? Obviously you have to have an advanced level of technique to be able to play in an orchestra and you have to have a certain level of confidence. But is there any one musical attribute that you think is absolutely critical? Or do you feel they’re all equally important?

DR: Every note is important. Alice Chalifoux taught that every note you play is important. We don’t gloss over notes or effects. Everything you play is important, and I think that’s how I approach orchestra playing. Naturally, rhythm is extremely important; phrasing; and ability to understand how to practice your part until you can play it flawlessly are also important.

HC: When the repertoire for an upcoming orchestral season would be announced, were there specific pieces that you looked forward to playing again?

DR: I always look forward to playing Faulkner, Strauss, Stravinsky, Ravel, Debussy. Those are my favorites. Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra is one of my favorite pieces.

HC: Each performance hall is different, but in general, where do you prefer to sit on stage? Where do you have the second harpist sit?

DR: Well, for many years in San Francisco, I sat almost in the center of the orchestra behind the clarinet, next to the French horns and right in front of the percussion. For ensemble it was the best place for me to sit. But for my ears, it was not a good place because I was sitting right in front of the cymbals. They were a little bit above and behind me right at ear level. It was deafening. The second harp should always sit to your right so you don’t have to follow the second harp. If they’re on your left, you have to see them and hear them. If they’re on your right, you neither see them or hear them, at least not very much. Then they can follow you.

HC: Did you ever use earplugs?

DR: Constantly. Actually, now I never practice without an earplug in my right ear at home. Onstage at Davies [Symphony Hall where the San Francisco Symphony performs], I have custom earplugs that are molded for my ears. They can be in all the time. Then I can pull them out in little increments to adjust for the level of sound I want to hear. If it’s extremely loud, I would push them all the way in. Earplugs are really essential for saving your hearing. When I was a teenager, I would practice without an ear plug, and my harp had a very resonant top register. My right ear would ring oftentimes when I would stop practicing. I realized that I was damaging my ear at that time. Of course, when you’re a teenager, you don’t think about things like that.

HC: Do you have any favorite halls to perform in?

DR: Well, the best hall I ever remember playing in anywhere, I only played there once. I believe it was with the Indianapolis Symphony. It was a symphony hall on the upper floors of a bank in Troy, New York. It was phenomenal. I never played in a place like that. The stage was slightly tilted down. Of course, it was all wooden, and it was built in the 1880s, I believe. It was a phenomenal place. I loved playing in Severence Hall in Cleveland when we’ve been on tour there. I love Disney Hall in L.A. It’s spectacular to see, and it’s a wonderful hall to play in. The Musikverein in Vienna was a great hall. It’s such an illustrious place to play with a great sense of history there. Carnegie Hall is also always very special. The first time I played there I was 19 years old, on tour with the Cleveland Orchestra, playing third harp in the complete ballet score of The Firebird. Playing with Alice Chalifoux and Martha Dalton in the Cleveland Orchestra was an enormous honor, privilege, and one of the musical highlights of my life. That was a special memory. That was before the hall was remodeled. It was actually much better many years before they redid it. It’s still a great hall.

HC: Is there a particular sound you look for in selecting a harp for playing in an orchestra?

DR: Well, you want the harp to have an even sound. You don’t want the harp stronger in the bass than in the upper register. You don’t want a weak bass and strong upper register. I was lucky in buying a harp back in 1979, a brand new harp that was incredibly even, and it’s a great harp. I have had a lot of trouble picking harps since then, so I’m not really an expert on picking harps, except I know you want a very even sound—a sound that projects, so evenness of sound is of the utmost importance.

HC: How do you warm up?

DR: I use different warmups every day. I do the Salzedo Daily Dozen, the Larivière exercises, Yolanda Kondonassis’s book, Salzedo’s Conditioning Exercises. I do one of these every day, and I try to instill in my students the importance of this. However, I don’t know that I’m always successful in convincing them. [Laughs]

HC: Can you name any conductors who you believe truly understand the challenges and intricacies of the harp?

DR: Well, that’s difficult. I could name some that don’t. [Laughs] Although I never played for George Szell, the long-time music director of the incomparable Cleveland Orchestra, from what Alice Chalifoux told me and from what I hear on their recordings, George Szell had a great appreciation for hearing the harp in the orchestra, and Miss Chalifoux said he always encouraged her to play out. To me, that is a conductor that understands the harp!

HC: I know that you have performed all of the major harp concertos with the San Francisco Symphony. Do you have a favorite?

DR: The Ginastera is my favorite harp concerto. I love the constant rhythmic feel it has and the virtuosity. It’s very impressive to hear, but it’s not overwhelmingly difficult. It’s just got a great sound, and I love playing it.

HC: Is there a funny anecdote or story that you could share with us about something that’s happened in your long career?

DR: In my first or second season with the San Francisco Symphony, we were playing a concert at Davies Hall, which at that time was still quite new. All of the quirks of a brand new building were still being worked out. We were playing a somewhat confusing modern composition. I could play my part fine, if I kept my place and my focus. However, in the middle of the piece, a light bulb exploded in the ceiling directly over me. Shards of hot burning material fell onto me that burned a hole in my suit pants, and I could smell burning hair. Needless to say, I got completely lost, and it took a while before I was able to start playing in the correct spot in the music again. Edo de Waart was conducting. He was glaring at me furiously. I went into his dressing room immediately afterwards and explained what had happened. He thenthought it was hilarious. I learned to be prepared for anything!

HC: In addition to your great success as a performer, you have also been a wonderful private teacher as well at the San Francisco Conservatory and the San Francisco Youth Orchestra. Do you have plans in retirement to continue playing and teaching?

DR: I certainly would like to—that would be wonderful. Right now I am sort of in transition, so I’m not certain. I’ll be living part of the time in Southern California, in Rancho Mirage, near Palm Springs, and part of the time in rural Missouri, a little town called Carrollton, near Kansas City. So it’ll be an adjustment, and I would like to play on a more local, smaller level than a major orchestra and to still do what I can to help others. •

I left my harp in San Francisco

When Doug Rioth took the stage for his first concert with the San Francisco Symphony (SFS) in 1981, Ronald Reagan was president, MTV was all the rage on television, and Beyoncé was a newborn. Just over 40 years later, Rioth performed his last concert with the SFS this past January and moves on to the next chapter where he can enjoy a seat in the audience.

Favorite orchestra part to teach? My favorite part to teach is the Bartok Concerto for Orchestra, perhaps because I grew up listening to it before I started playing the harp.

Most important characteristic for a harp student to possess?

A disciplined work ethic.

Favorite footwear at the harp? At home I practice in my socks.

Favorite orchestra part? My favorite orchestra parts are by Wagner.

What would you do for a living if you weren’t a harpist? If I wasn’t a harpist, I’d love to be a long-distance truck driver.

Midwest or West Coast? In retirement I will be living in Missouri and Southern California. I choose both.

What do you do for fun? I enjoy studying American Sign Language.

Better tourist destination: Golden Gate Bridge or Alcatraz? The Golden Gate Bridge is much nicer than visiting Alcatraz, in my opinion.

Proudest moment of your career? When [conductor] Michael Tilson Thomas gave a nice tribute to me after my last concert with the San Francisco Symphony at the end of January 2022 when we played Mahler 1. I realized that I must have done a good job.

Do you tune by ear or with an electronic tuner? I use an electronic Peterson Strobe tuner. I could not possibly have played in tune with the San Francisco Symphony without it!

What will you miss most about playing with the San Francisco Symphony? I will miss my colleagues and the wonderful sensation of hearing great music day after day, week after week. It was a gift to have such a career.

What won’t you miss about the job? I will not miss the incredible stress.

Beach vacation or mountain getaway? What is a vacation? I guess I will find out.

Musical guilty pleasure? I love Metallica, especially the albums the San Francisco Symphony made with them—S&M and S&M 2 (pictured right).