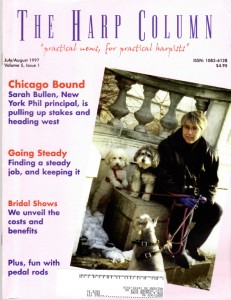

Then and now

Sarah Bullen, pictured top with her two dogs (an Aussiedoodle named Finn and a St. Bernard mix named Sam), first appeared on Harp Column’s cover in 1997 when she left the New York Philharmonic for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. For a walk down memory lane, read our interview with Bullen in that July/August 1997 issue.

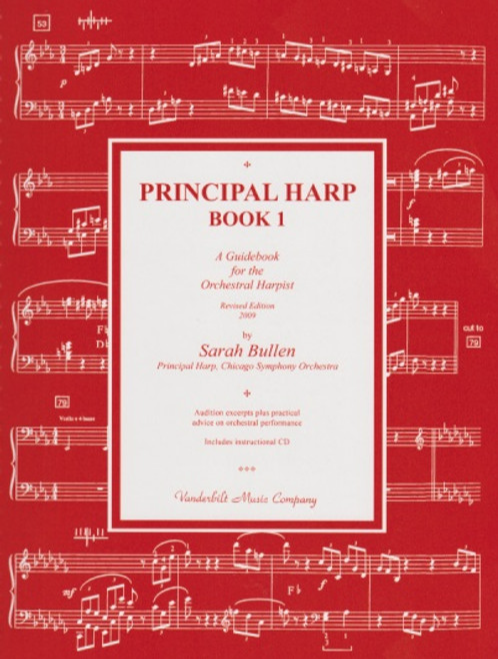

Sarah Bullen literally wrote the book on orchestral harp playing. Her 1995 book, Principal Harp: A Guidebook for the Orchestral Harpist, quickly became required reading in orchestral repertoire classes and a must-have resource in every harpist’s music library. She went on to write a second volume of Principal Harp (Vanderbilt, 2008), and most recently The Orchestral Harpist (Harp Column Music, 2023), which explores some of the big orchestral repertoire that calls for two harps.

During her career, Bullen’s name became synonymous with American orchestral harp playing. You could feel the seismic shift in the harp world when she made the move from the New York Philharmonic to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) in 1997. When Harp Column interviewed her about the move to Chicago, Bullen had clear goals and motivations for taking the job. She was hungry for the challenge and saw Chicago as an opportunity to elevate the instrument’s status. She stayed with the CSO until her retirement in 2021, following a 40-year orchestral career that started with the Utah Symphony in 1981, followed by 10 years with the New York Phil and 24 years in Chicago.

No one has done as much for orchestral harp playing in the United States as Sarah Bullen. Her bold style and no-nonsense approach led the way for a generation of harpists. Another major shift in the harp world could be felt when she stepped down from the CSO. We caught up with Bullen, now two years into retirement, to talk about her legendary career and what the next chapter might hold.

Harp column: You got your first job with the Utah Symphony in 1981. You retired from Chicago in 2021. Forty years is a long time. Is there anything that you could point to about the job of a principal harpist that changed markedly between the time you started and the time you retired?

Sarah bullen: No. In fact, I have a fun anecdote about this. When I joined the [New York] Philharmonic, I had been in Utah for almost seven years. A couple of months after I started in New York, there was a Live from Lincoln Center broadcast. I believe Capriccio espanol was on the program. I thought, “Oh my god, how am I gonna do this?” And I remember telling myself, “You’re in a gymnasium in southern Utah playing a school concert. It’s the same thing. The expectation is the same.” You want perfection, or as close to it as possible. Obviously, there’s a huge difference between venues, but my expectation for myself was the same. I think this goes to the mindset and integrity of a committed, serious classical musician. I don’t care if you’re in a community orchestra or the New York Philharmonic, you always bring your best to any performance.

HC: When we last interviewed you for the cover of the magazine in 1997, you had just taken the principal job in Chicago. Now in 2023, you’ve been retired from that position for two full seasons. One of the reasons you said you took the Chicago job was because you said you like a good challenge—that intrigued you. After 24 years in that position, how did you come to the decision to retire?

SB: Why did I retire, being that I do like challenges? I had a strong sense that there was another chapter in my life that I was wanting to embark on, and I have a lot of other interests other than just harp. A big part of it, too, was that my wife, Dyan, passed away in 2020. And I also think COVID had a lot to do with it. I remember when I finally went back to work, which probably wasn’t until the summer of ’21, a couple months before I retired, it just felt so different for me to be back as a working musician without Dyan, because she was always there, she was just such a rock for me. You know, I like to be honest, and I think also what was happening was the pressure I felt. I’ve always had very good nerves, and I maintain good nerves in performance—the ability to perform and not feel handicapped by nerves. But I think I wasn’t tolerating or not wanting to tolerate the pressure of performance anymore.

HC: Do you think that shift in how you felt about performance pressure happened during COVID?

SB: If I think back to a sabbatical I took back in about 2008, that’s when I first started thinking I could see myself retiring. The sabbatical was really nice. I thought maybe I’d play another 10 years, but I ended up making it another 15.

HC: The schedule of a principal musician in a top orchestra is grueling. Tell us about what that is like day in and day out.

I don’t care if you’re in a community orchestra or the New York Philharmonic, you always bring your best to any performance.

SB: Anyone who is part of, let’s say, the top echelon of classical musicians, the expectation is perfection. You’re striving for perfection all the time. It’s a noble profession in a way. We have great reverence for the repertoire we’re playing, and it’s drilled into us that we honor what’s on the page. Our preparation is a lifetime of study. I felt like, in my later career, it was actually getting easier in a certain sense, because I’d done things for so long. Things that used to scare me were more fun in my later career, because I knew it better, and I had a better perspective of what my role was. I think early on in a career, you’re so consumed with ambition and hoping you make it—that’s fueling your trajectory. I felt like I was flying by the seat of my pants early in my career—I had a lot to learn. It’s assumed that you love what you’re doing. My love of the harp goes back to when I was 8 years old, so it’s fueled by that love. Then that ambition starts creeping in, and you want to find a place for yourself in the world. I can remember being a teenager and listening to a recording of the Debussy Danses and just crying. I so want to do this—there’s this aching desire for accomplishment and finding your place in that world.

HC: Tell us who guided your early years at the harp? Who nurtured this desire to play the harp?

SB: I was lucky. I studied with Grandjany at age 10, which was amazing. But then also, I studied with Mildred Dilling. I went to her when I was about 15. She and Grandjany were amazing in different ways. Grandjany was an incredible master, but more intellectual and bookish, just wonderful. But Dilling was like Technicolor. I grew up in the New York City area, and I would have a lesson with her on a Saturday, and she’d say, “Do you want to go to the ballet tonight?” I was 15, and so I asked my mother if I could stay over at her apartment. She had this big sprawling apartment on East 52nd Street, a floor below Shirley MacLaine, the actress, who I used to run into in the elevator. I didn’t even know who she was. The whole experience was magical. Dilling was magical. And there was always a little bit of magic in the harp for me. I can remember being very young and seeing sparks fly through the harp strings and thinking, “Okay, I’m gonna follow this.” I always had this sense of where I wanted to go and how special the harp was. Music became a refuge and a focus and something that I followed and devoted myself to. It requires that intense focus and commitment.

HC: Again, going back to when you started in Chicago, in addition to taking the job because you thought it’d be a challenge, you also said that you were looking forward to the opportunity to elevate the instrument in both how it’s viewed and how it’s compensated. In the last 25 years, do you think it’s gotten better?

SB: It’s much better now. At the time I was the highest paid harpist. I was in a very good negotiating position, because I was leaving a major orchestra for major orchestras—that’s ideal. It’s like when Emmanuel [Ceysson] went from the Met to [the Los Angeles Philharmonic]— he was in a great position.

I always had this sense of where I wanted to go and how special the harp was. Music became a refuge and a focus and something that I followed and devoted myself to.

HC: What do you think about these orchestra auditions where no one is chosen?

SB: I think it’s an unfortunate trend these days. I think it’s a trend. There’s kind of a mindset in auditions, and I’ve seen it, where “no one is good enough to get in my orchestra.”

HC: What advice would you give your younger self as you were starting out and taking orchestral auditions?

SB: Lighten up. Don’t be so insecure. I’m an interesting blend of being very confident and very insecure—like flip sides of a coin.

HC: I never would have guessed that you’re insecure.

SB: I have full confidence in my ability to execute the part, even if it’s a bad part and I have to rewrite half of it. I’ll get the job done. But then the imposter syndrome creeps in, and you have to manage your emotional equilibrium. Yes, I’ve always believed in my strength as a musician. I know what that power feels like inside of me. That’s probably what enabled me to do what I’ve done professionally. But that doesn’t mean I was able to get out of my way to enjoy the run. One of my students said to me, “Your students love you because you’re so human.” I’ll show those parts of myself. I’m not just trying to pretend what a hotshot I am all the time. I don’t like all of the posturing. I want authenticity.

HC: In our 1997 interview, you said, “I think a winning attitude is one in which you’ll always find a winning solution. Life is nothing but problem solving. And we have to figure out a way to get from point A to point B on a daily basis.” How do you think that attitude served you throughout your career?

SB: It served me well, actually. You know, stuff happens, and you’re gonna figure it out. I’ve wasted a lot of time worrying, but even when the worries manifest and happen, you’re gonna deal with it. It’s not to say that they don’t wear you down a little bit. I am 67, you know, I’m getting older. But, yes, if there’s a problem, you need to find the solution. I tend to actually react very quickly, and probably too quickly—I’ll jump to a solution. I’ll be a little too impulsive sometimes. But as a musician, you’re handed a part that has sections that are driving you mad, so you have to find a solution. That solution might involve eliminating a hand, or raising it an octave or lowering it—it has to be something you know can work in performance, in the real world, at the right tempo. It’s my pet peeve when people say you must play every single note on the page on something like that. That’s ridiculous. And, though I think it’s particularly problematic for harpists because a lot of composers don’t understand how to write for the harp, it’s not just harpists that [have to make parts playable], it’s that way for every instrument. I’ve talked to colleagues many times over the years who say, “Of course you don’t play everything that’s in a part Wagner wrote.” It’s a dirty little secret that I’m willing to admit, but most people aren’t.

An open book

Sarah Bullen published her first book, Principal Harp, Book 1, in 1995, giving aspiring harpists a glimpse into the technical and musical nuances of world-class orchestral performing. She released Principal Harp, Book 2 in 2008.

Bullen has written a new volume of orchestral edits, tips, and advice, The Orchestral Harpist, published by Harp Column Music in late 2023. “In each part, I always draw on what was giving me problems when I was approaching them,” she says. “I’ve come up with solutions that I wish I had known about when I was first playing these.”

HC: You go a step further than admitting it—you literally wrote a book about it—several books, actually. Your newest book of edits and markings for orchestral harp parts just came out, but the parts you cover in this book are a little different from what you covered in your first two books—they are big harp parts, but not ones typically seen on audition lists—and you included a lot of harp 2 parts—how did you choose the pieces for your new book?

SB: Well, most of the pieces are performed often and have some spots that I wanted to address and discuss. In each part, I always draw on what was giving me problems when I was approaching them. I’ve come up with solutions that I wish I had known about when I was first playing these. Also, there are some things that might be easy for someone with bigger hands, but I don’t have particularly big hands, so they were hard for me. So these are the solutions I came up with. I also thought it was important to include the second harp parts because any young harpist coming up in the world is going to be playing second harp, but you don’t study [those parts] in school even though some of them are every bit as tricky as the harp 1 part.

HC: What is one thing that you think most harpists could do to improve their orchestral playing?

SB: Well, rhythm is the number-one deficit that most harpists have. Something that Grandjany advocated with me was counting out loud. But I think the greatest teacher [of rhythm] is just sitting in an orchestra, and if you’re not sitting there counting, you’re going to fail. I can remember my first exposure to orchestral playing was at Interlochen when I was 16. I was a good little solo harpist, but I was clueless in orchestra. I could play the dickens out of the Nutcracker cadenza, but I might not know where to put it or how to play the rest of the part. I can remember asking a violin player to tell me when to come in. [Laughs] Even in Utah [at my first job], I was friendly with the celeste player, and I went over to his part to look at something we were doing in the Bartok Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, and he had written in his part “don’t listen to the harp.” My point is, I had a lot to learn.

HC: And it sounds like you essentially learned on the job.

SB: Absolutely—and you learn quickly. Ensemble skills for harpists are woefully inadequate. One huge reason is, and I said this in the book, the parts are little snippets here and there. We’re not really part of the orchestral blend like a string player is who is constantly playing and weaving in and out. Our parts are generally not like that. Developing ensemble skills is crucial for harpists. It is what I was lacking. My best friend at Juilliard was [harpist] Gretchen van Hoesen. She hired me to play a second harp for Symphonie Fantastique, and about a week before the first rehearsal she asked me if I had looked at the Berlioz yet. And I said, “Oh, no, don’t worry, we’ll be fine.” She stared at me and said, “No. It won’t be fine.” She quickly got me to realize I needed to take this seriously. I didn’t quite understand how serious the pursuit and study needed to be. You need to master these parts before you come into the first rehearsal.

HC: You spent your career tackling big challenges at the grueling pace of a top tier orchestra. Now that you’re retired…

SB: …what are you doing with your life? [Laughs]

HC: Do you find yourself trying to fill that space with something else?

SB: It’s been a challenge to find things that hold my attention, but I’m an adjunct professor at Indiana University—I teach a weekly orchestra rep class. It’s on Zoom, but I’ll go back once a year. The other thing I’ve been doing is building houses.

HC: Literally?

SB: Well, I’m not quite like a builder, but I’ve now bought and sold two properties where I built an ADU—additional dwelling unit—a cottage in your backyard. They are a big thing out here. I have a new partner and we both love doing this, so it’s been really fun for us. To be honest I’m struggling a little bit with where the harp fits in my life right now. I love teaching and could teach all day long. I know that this core of me is still there. I don’t want to lose touch with that, but I don’t need to access it all the time like I used to. I’m still playing, but I don’t have that drive anymore. I don’t need to prove anything. Honestly, there’s so many great artists out there, and the world doesn’t need to hear my recording of anything. Gloria Agostini was one of the top commercial recording studio musicians in New York, and I had some lessons with her after Juilliard. I told her I want to be the best harpist in the world. And she says, “Well, that’s ridiculous. You can’t be the best. It’s enough to be one of the best.” I thought that was great because it speaks to the grit and drive and love that I think is required to excel. I absolutely had that, but now I don’t have that. I still love the instrument. I’ve spent my life devoted to it, so that’s still there, but I’m trying to carve out new accomplishments for myself. I mean, look at all the great harpists in the world now. •

Straight talk with Sarah

Chicago deep dish pizza or New York style pizza?

New York.

Most unexpected item we would find in your gig bag?

Wite-Out.

Favorite place you’ve visited on an orchestra tour?

Copenhagen or Amsterdam; I also loved Buenos Aires. That is clearly one of the huge benefits of being in a top orchestra—I can’t really count the number of countries I’ve been to. It’s been amazing. New York actually toured to more exotic places, like Istanbul, North Korea—I wasn’t there for that one—but New York had a more exotic reach.

Best and worst parts about being a harpist?

One of the best things about being a principal harpist is that you can really shine and soar as a soloist. You can feel that thrill, particularly when you nail the part. It’s thrilling. I think the worst part of being a harpist is tuning and worrying about a string breaking.

Binge or slow drip with Netflix shows?

I prefer binging.

Craziest thing that’s happened to you during a performance?

I was in New York subbing for some European orchestra. They were on tour and their principal harpist got sick. So I got this call asking if I could play the Bartok Concerto for Orchestra the next day. They were performing at Avery Fisher, now David Geffen Hall, and my harp was already there, so it was a no-brainer. So I went and played, and during the concert the second harpist collapsed forward into her music stand and went flat on the floor. This was before my entrance in the first movement, and I’m thinking if someone doesn’t do something soon, I’m gonna have to go backstage and get help. Right at that moment, two of the back-stand violinists got up and dragged her, feet-first off the stage. The harps are really close to the back of the stage, so they each took a foot and dragged off stage, and I made my entrance. But then in the fourth movement with the big chorale, she came back on stage looking like a ghost. She played the fourth and fifth movement, and when we came off after it was over, there were paramedics backstage saying, “Ma’am, you need to come with us, we think you’ve had a heart attack,” but she refused.

Favorite orchestral part to play?

Strauss, particularly Ein Heldenleben, Debussy, I always love Stravinsky, the Mahler “Adagietto,” Tchaikovsky ballets, some Puccini operas. Since I retired, I’ve been listening to a lot of recordings of the war horses of our rep, and I’m listening and thinking, “Where’s the harp? I can’t hear it! You’re killing yourself on these parts, and I can’t even hear you!” I know it’s not the harpist’s fault, but you know how hard they are working. All these years I was too busy playing [these parts] to realize it.

Part that you wouldn’t play again, even for a million dollars?

Probably Wozzeck.

Favorite way to unwind?

I love hiking with my dogs or riding my bike in the woods. I love working on house projects. I love to cook to unwind. I don’t follow recipes—I’m very eclectic. In the morning, I have my two cups of coffee then take any leftover coffee and add ice and seltzer or Diet Coke to it, and that’s like my version of an iced coffee.

If you weren’t a harpist, what do you think you would have done for a living?

I think I would have loved being a builder. •