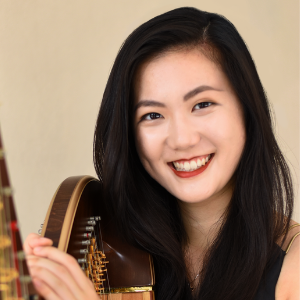

We often see a person’s successes from afar. Their accolades might appear shiny and effortless from where we sit, even though that is never the reality up close. I knew Hannah Cope Johnson’s name before we officially met in 2021 while we were both studying at the New England Conservatory. She has won top prizes of national and international competitions, subs regularly with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and was principal harp of the Sarasota Orchestra during the 2022-23 season.

Over the past couple of years, I have had the opportunity to get to know Hannah better and see her harp life up close. I’ve seen her successes and her defeats, I’ve heard her play countless mock auditions, and I’ve observed how hard she works. Hannah doesn’t let anything slow her down, and I am constantly in awe of her work ethic and professionalism. So when Hannah told me she won the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra (commonly called the Met) audition last year, I knew I had to share her story with other harpists.

I caught up with Hannah at the Tanglewood Music Festival where she was subbing with the Boston Symphony Orchestra this summer. We took time in between Götterdämmerung rehearsals to talk about her first season as principal harp at the Met, and she provided some insights to her audition preparation and process.

Harp column: Welcome back from your tour, and congratulations on completing your first season at the Met! Tell us what your first year has been like.

Hannah cope johnson: Thank you! Well, this year has been really inspiring and incredible to play with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. I finished this year with a total of 150 performances with the Met, and I’ve already learned so much in one year from my colleagues. It’s really an inspiring place to work, and it’s been amazing to be surrounded by musicians that are so sensitive, really amazing listeners, and really fantastic accompanists. My music director, Yannick, too, he’s just full of energy and a very inspiring person.

HC: What is it like working under [Met Music Director] Yannick Nézét-Séguin?

HCJ: It’s really a positive environment with him. He’s kind of like the Energizer Bunny. I don’t know how he does it, but he’s always positive, full of energy, not afraid to laugh at himself or us. When he’s on the podium, he’s always very inspired. Nothing seems overly rehearsed in his movements, and it feels like it’s naturally coming out of him. It changes from night to night how he does some things. I really appreciate that in a conductor, because it keeps it fresh and alive when you play the same opera many times. He’s a fantastic music director, and he also communicates very well to me. It’s just a great environment. It’s so nice and uplifting.

HC: What would you say, in your training or ensemble experiences, best prepared you for this position?

HCJ: It’s hard to answer that because in a lot of ways, I’ve found myself learning so much this year that I don’t think I could have learned anywhere else.

HC: I guess a better question is what have you found to be the biggest adjustment or what kind of challenges have you faced in this job so far?

HCJ: My opera experience was relatively small before coming here. I had done four operas in my life before joining the Met. I knew basic ideas about opera and accompanying singers, but a lot of what I’ve learned this past year has to do with timing and how you need to adjust your timing depending on the role you’re playing in the music and the context. Starting my professional career in the Sarasota Orchestra and subbing with the Boston Symphony, I’ve learned about how there’s often a delay from the stick in professional orchestras. That’s a timing thing you have to learn depending on the conductor, on the group, on the music, and the tempo of the music affects that as well. It’s always a little bit different for each group.

But playing at the Met, I’ve had to keep that concept in mind and consolidate that with my ever-shifting role as the harp in operatic repertoire. The harp’s function in opera repertoire is really significant and, I would say, more involved than a lot of symphonic repertoire. Especially because we’re accompanying a singer, and how do we accompany a singer? We need a rhythmic thing going on under that melody line and often, the harp ends up providing that framework for the singer to sing over the top of. Often I’m the only member of the section present in the pit, so it’s like I’m controlling everything, and it happens over and over again.

Hannah takes the hot seat

Favorite post-performance meal:

Well, there’s a burger place I love called Lovely’s Old Fashioned. I’m a cheeseburger person. There’s also a food truck outside my apartment that has shawarma.

Guilty pleasure music?

I don’t feel guilty. Do I feel guilty about any of the music I listen to? I love The 1975. It is a pretty basic group to like, but I’m a pretty basic girl.

What pets do you have? I have two cats. Their names are Hobbes and Zeus, and I just love them so much. They bring a lot of joy to me and my husband.

Heels or Flats?

I’m a flats person.

Do you have a favorite harp solo piece?

Hard to pick a favorite. I just did the Tournier Sonatine, which I have wanted to play for a really long time, and I’m obsessed with it. I love that one.

What’s your pre-performance routine?

I don’t really have one. I kind of just shower and get dressed and show up.

If you weren’t a harpist, what would you want to do?

The practical answer is a mechanical engineer. The impractical answer—probably a chef.

HC: It’s always more fluid in opera too, because you have to depend on the singers and everybody else in the ensemble, right?

HCJ: Yes, one concept I’ve been really working on this year is marrying the two ideas of being the leader and also accompanying something else. There’s a way to do both. Like, follow but lead. I don’t know how else to describe it.

HC: Follow but lead—that’s great.

HCJ: It’s something I never really had the opportunity to learn anywhere else. I wish I had a collaborative piano class to accompany singers in college. That would’ve been amazing if I could have done something like that, then I could have learned some of those concepts. But it’s just something you have to learn on the job in the harp world, and it’s been really, really fun to learn.

HC: What is a typical day like for you?

HCJ: Some days I’m lucky to only have a show in the evening, but it depends on the day. Some days I will have rehearsal in the morning followed by a concert in the evening. Typically our rehearsals don’t start till 11 a.m. They want to give the singers time to get their voices warmed up before rehearsal. Plus, we play six or seven shows a week, and most of us have played a show the night before, so getting to start rehearsal at 11 instead of 10 is nice. Generally I’ll get up, go to rehearsal, and I’ll spend the afternoon practicing or doing some studying on my own. But I’m always careful. I’ve learned the hard way that I have to ration my energy, because the most important part of my day, the actual performing part of my work, is happening at the end of the day. If I use all my energy and focus rehearsing in the morning, practicing all afternoon and studying, I’m exhausted when the evening comes, but I have to go play a show.

HC: And it’s usually a long show too.

HCJ: Yes, they’re always long. So I’ve learned to be very intentional about stopping what I’m doing usually in the later part of the afternoon. I’ll go watch TV or play with my cats or just force myself to relax so that I’m fresh for the show.

HC: What was your most memorable moment or show this past season?

HCJ: I have to say Tannhäuser was my most memorable opera. It’s so difficult to play. It’s a big harp part. The tenor, the title character of the opera, plays a harp while he sings. Actually, multiple characters—they’re kind of like bards, so they play a harp while they sing in several of the scenes. As the harpist in the pit, you are their harp. They’re up there [on stage] playing air harp, and you’re down in the pit playing the real harp. I have to really lock in with the singer and be his harp, and it was really satisfying once we got it. After the shows, the tenor would go take his bow. Then he would walk over to me in the pit and he would gesture to me every time. He gave me props after all the shows. That made it fun. I can’t remember if there were eight or nine shows in total. I actually got COVID in the middle of the run, and [harpist] Helen Gerhold was my hero. She was my cover for that production, and she came and played one of the shows with zero rehearsal. She’s a hero for that. Another one of them, I was feeling ill and I wanted to leave early. But I stuck it out and played. They’re playing harps on stage, so there’s got to be a harp.

HC: Could you take us back to the moment you found out that you won the job?

HCJ: I remember I was the last one to play in the final. I was the third candidate of the three finalists, so once I was done, they tallied the votes. There’s no deliberation at the Met. The audition committee members anonymously vote for who they choose, then the votes are tallied, and that’s it. There’s no deliberation because that’s the way they run it. They really want it to be fair. Since I was the last to play, they were basically ready with the answer once I had finished. I had only a few minutes to calm down from the adrenaline before they brought us into the personnel manager’s office—me and these two fabulous harpists on either side of me. Then they said the committee has voted, the votes have been tallied, and I was the winner. My heart is pounding just remembering it—so much shock, so many feelings. I remember tears sprung to my eyes immediately and I gasped and covered my mouth. Then I felt this uplifting feeling instead of that all-too-familiar letdown. We’ve all had that letdown when they say someone else’s name. It was this realization that, whoa, they said my name. You’re expecting the bad news, and it’s the good news. It’s shock, just pure shock. But then I was so aware of these two harpists looking at me, and I remember feeling uncomfortable too, because I knew what it was like to be them and be disappointed. Of course, I felt overjoyed, but I felt the need to reach out to both of them too. It was such a bizarre moment in my life. But then they ushered me away to go meet the committee. They had to go play Boheme in 45 minutes, but they all were waiting because they wanted to meet whoever this person was that they voted for.

HC: Was the entire audition behind a screen?

HCJ: It was all behind a screen so they had no idea who I was. I think they brought in my resume with my name cleared out after the vote was complete so by the time I went down there, they knew I went to NEC and they had revealed at least some things about me. They told me how beautiful it was. Some of them told me that they knew from the first round that I was going to win. I had a couple of them come up to me and ask what number I was in the prelims. (They randomized our numbers after the prelim round and they gave us new numbers in the semis) I told them my number and they said, we heard you play and we thought, I know that person’s going to win. So for whatever reason, the style that I played really spoke to some of them. It was really cool to hear these amazing orchestra musicians telling me that.

HC: I’m sure a lot of that was also due to your preparation and your training. What did you find the most challenging about the preparation for this audition?

HCJ: I had done a couple auditions before this one, but they were all the standard orchestra stuff. For most auditions that come up, I know most of the excerpts and just have to learn one or two that are weird that they’ve put on. But for this list, I think I knew only three or four of the 19 excerpts. I had to start from scratch with most of the list, which is hard because I can’t rely on any previous experience. But in some ways it was kind of nice, because I got to have a fresh start with a lot of the excerpts. Instead of walking into the audition with trauma from times I really biffed it on a piece, I had no such trauma for most of these excerpts. So there were pros and cons to that, for sure.

They had 80 people send in a resume, and they needed to cut it down. They didn’t have time to hear 80 people play a prelim, so there were about 30 people that they invited to the live round right away based on the resume, and they asked the rest of the 50 candidates to send in a recording before they would invite us to the live audition in New York. So I had to send in a recording of a handful, I think five, of the excerpts.

I was finishing up my season in Sarasota when the recording was due, and I had just played with the Boston Symphony that month. It was April, and I had booked a lot for myself. I remember I was stressed trying to learn excerpts and get the best take that I could. All I was focused on were those five excerpts. I hadn’t thought about the other 14 things on the list. I had to just worry about the recording and hope that I got it.

HC: And you did.

HCJ: I did. I submitted the recording, and I remember they called me immediately the next day. I applaud the way they run their auditions. They don’t make us wait a week after sending the recording. They’re very good about it, and they consider the candidates. Anyway, they called me and said, hey, you’re invited. I remember I was surprised they called me instead of just emailing me, so I asked how many recordings got in, and they said four. I think it was just four.

HC: Wow, was that out of 50?

HCJ: Yes, it was a really steep cut for the recordings. So that helped make me feel like they liked something about what I did. Now I have a month left until the audition, so I need to make these other 14 excerpts sound good. So I packed up all my Sarasota furniture, put it into storage, and drove up to Boston. That was a week gone, and I didn’t get anything done. Then I thought, okay, now I’ve got to get everything else ready in four weeks.

I think I had one gig that month, but I just purposefully spent my time digesting all that new opera excerpt music. I felt like I was pressed for time, but it ended up being just right. It’s hard to calculate that stuff sometimes, and I lucked out in that way. I was really deliberate in the way I prepared. I made recordings of myself playing, listened back to it, and I was so picky. I continually challenge myself, asking what could make this better, where could I add a little bit of something special, something sparkly to this part to make it interesting and not just correct? I wanted every moment to be intentional and interesting. I also played 14 mock auditions as part of that preparation before the audition.

HC: In one month?

HCJ: In one month. And I have a lot of harpists around the country to thank. They got on Zoom, listened to me, and gave me ideas of things that I could try. A lot of really great ideas and a lot of little things I implemented, so I have a lot of harpist friends to thank for that. It was really cool too, because towards the end of the prep, the mock auditions got into the teens and people would tell me an idea. There’s nothing wrong with it, but I would think, no, I like the way I do it. I think I’m going to be more convincing this way, so I stand by my decision. I got more and more secure about the way that I was playing it. Not to say there’s a right or wrong way to play anything, but I think that’s hopefully a testament to how much time I had spent with it. I think many would agree with me that if you have a testimony of it, then it will sound good. If you are convinced, you will convince.

HC: Definitely. You want to play the music in the way that you hear it too.

HCJ: For sure. I got to that point by the end of the process of the mock auditions. It forced me to be nervous over and over, but it also was a way of testing my confidence in my ideas. It got me to a point where I liked the way I did it. So going to the audition, it helps you be less worried that your hand is going to turn over too much during Salome and that you fall off the string. It helps you quiet down all those thoughts and just think, this is what I do on this part. It helped me get to a really great headspace. I’ve played auditions where I was not in that headspace. It takes a lot of work to get there, but I feel really lucky and grateful that I felt like these stars aligned that I was able to get there.

HC: Would you advise harpists to have that many mock auditions in order to prepare, or do you have more advice for audition preparations?

HCJ: I think for me, the mock auditions are huge. Some people might not need them as much, but I can only speak to what is my process and what I feel I need. That’s something I learned in my undergrad. If we were playing a recital, my teacher made us play 10 practice recitals before the actual recital, and she would make us turn in a piece of paper with a log of what date and who it was for.

HC: Would it be a month before?

HCJ: Yeah, you wouldn’t start that mock performance process until three weeks before the competition or the recital. I thought it was really helpful, and I’ve always tried to do that ever since. And part of it is that it’s helpful to get feedback from other people. Other people have a lot to offer, and they have great ideas that you might not have considered. But also, the first several mock auditions, I’m always nervous. I’m so aware that someone is watching…they feel like they don’t go very well, because I’m not thinking about the music. I’m obsessing over what someone else thinks. But that’s good, because as you go, you get more comfortable and you get more used to that feeling of…okay, I’m conveying something to them. I’m going to show them what I’m trying to say, and I’m not going to worry about what they think. There’s the whole physical part of being nervous. Ideally, the repetition of the mock auditions will help with managing the physical aspect of being nervous. But it’s also mental, I think. It helps build your confidence, so I’m really big on the mock auditions.

HC: What are you most looking forward to in the next season?

HCJ: Next season we’re doing Salome, which I’m excited for. Yannick is conducting that. We’re doing a new production of Aida, which will be cool too. We’re also doing Les Contes d’Hoffman at the beginning of the season. They actually play harps on stage in that show too. It has some fun parts.

HC: Anything else aside from the Met performances?

HCJ: I’m doing a duo concert, a flute and harp concert with Chelsea Knox, the principal flute. We’ll be doing a chamber concert in New York City in April. I’m also going to do a harp quartet concert in Sarasota with some of the past principal harpists of the Sarasota Orchestra. So it’s a generational Sarasota principal harpist quartet. I’m making some of my own arrangements for that concert. It’s a fun kind of creative outlet for me to try to reimagine music for a different ensemble. I love doing that.

HC: Do you have advice for young harpists who want to be in your shoes one day?

HCJ: I think in order to get to a principal harp position, there’s one thing that you can’t do…and that’s give up. You have to just keep trying and know that it’s a hard road. We get told no a lot in our careers, but it’s part of the deal. We’re pitted against other people. It’s not even about being the best. We’re trying to be the right fit. Do your best to surround yourself with a network of people who can help you. It’s incredibly taxing on our emotional health and our mental health because we’re so vulnerable, and we work so hard and then get told no. It’s hard. That’s not a small thing to work through in pursuit of a career. I’ve had the luxury of having a husband for eight years now who has supported me constantly—financially, emotionally—so that I could spend the time and energy to keep working on my craft. I’ve been really fortunate for that. I would say if you have some situation like that, where you’ve got parents supporting you or you’ve got a patron of any kind, take advantage of that, and really just keep going. That’s the one thing that you have to do. You have to keep going. One other thing I would say is that sometimes we get burned out, and it’s hard to care about everything we’re doing. We’re tired. We’re overworked and trying to practice for everything. But really, try to stay present in caring about the art that you are creating. That is the purpose of what we are doing. We’re creating art. We’re artists. Keeping that close in your heart and keeping that in your focus as much as you can gives you the energy to push through. Stay grateful for every opportunity to make music. It’s really a privilege we have that we spend our lives this way. •