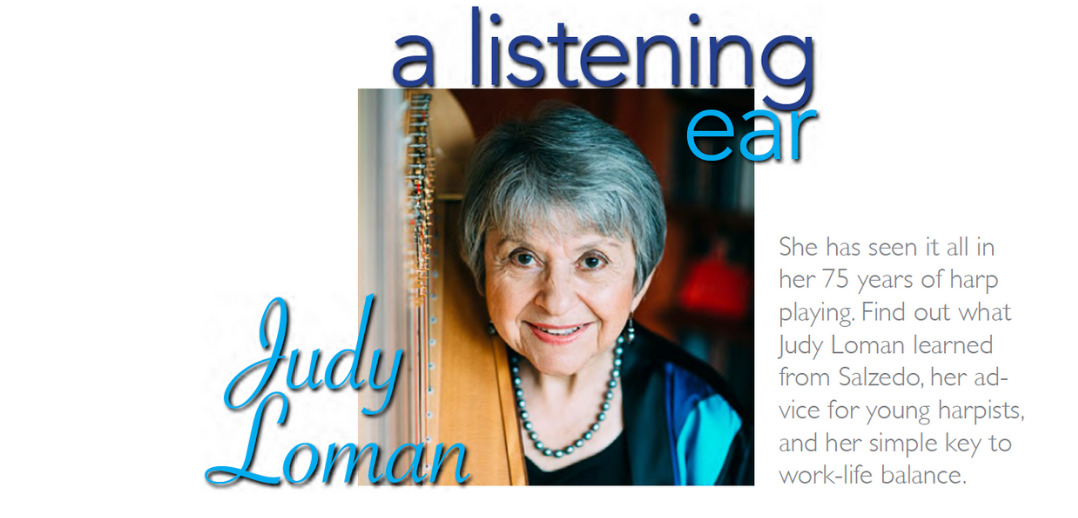

It’s difficult not to use superlatives when writing about Judy Loman. She is a walking superlative. She is universally respected as one of the harp’s foremost artists of the last 50 years. Her teaching has been transformational to the scores of students she has taught in her career. She is one of the most prolific recording artists our instrument has ever seen. She is an exquisite soloist. At the same time, Judy Loman is one of the most humble, down-to-earth people you will ever meet.

When we interviewed Loman for the cover of our November/December 1996 issue, she was still principal harpist with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, a sought-after teacher, and a recording artist for several different labels. Over the last 20-plus years, Loman’s stature in the harp world has only grown. Still an active performer, teacher, and recording artist at the age of 83, Loman found time in her busy schedule to sit down with us and share her thoughts about the harp nearly a quarter century after our first interview with her.

Judy Loman then and now

A lot has changed in the last 20 years. As we enter 2020, we’re checking back in with artists we featured on our cover prior to 2000 to find out how their corner of the harp world has changed—and stayed the same—since we first talked to them 20-plus years ago. You can read our first interview with Judy Loman in the November/December 1996 issue of Harp Column in our back issue archives at harpcolumn.com.

Loman stepped down from the Toronto Symphony Orchestra (TSO) 18 years ago at the age of 65 (the retirement age mandated by the orchestra), but she says it feels like yesterday. “Since I knew I would be retiring at 65, I was making plans for what I would do when I retired. I thought, ‘I’ll do a lot more arranging, and I’ll perform more, and I love teaching, so I’ll do more of that.’ Although I’ll miss Mahler and Strauss and all of the great composers, I can listen to them at any time, and I’ll be teaching that repertoire anyway. So I just felt that it was right,” she says. “ And then the year I was to retire, the [TSO music director] Jukka-Pekka Saraste called me into his office and said, ‘We’d really like you to stay on.’ But I didn’t even need to think about it. As much as I loved playing in the orchestra, I thought it was time to go.” Loman admits that as you age, your eyes lose a bit of sharpness they once had and your ears don’t hear quite as clearly as they once did—crucial skills in ensemble playing.

Sitting in front of the percussion section in the orchestra for decades probably took a toll on her hearing, Loman admits. Back in the day, she says orchestral musicians never thought about wearing ear protection. But even if she had known the possible risk to her hearing, she’s not sure she would have worn ear plugs. “I couldn’t sit in the middle of all that sound in the orchestra and obliterate it with ear plugs. I loved sitting in the middle of the orchestra because of what I heard—letting the sound go through me.”

Loman says her years in the orchestra made her a better soloist and a better teacher. “If you’re in the orchestra doing something like Mahler’s “Adagietto” or the “Berceuse” from Stravinsky’s Firebird, or any piece where a special sound is needed and you only have a few notes or a few bars to show that special sound—I think that is something that hones your way of listening to how you play. That’s what I found really helped me in my solo playing. And then my solo playing became better, and it helped me to play better in the orchestra. Plus, just being in the orchestra enlarges your whole idea of phrasing and how you read what’s on the page and what isn’t on the page. I learned so much from conductors, violinists, piano soloists—you learn so much just by listening. Being in the orchestra was, after Salzedo, my greatest teacher.”

These are a few of my favorite things

Favorite orchestra part to play: “Probably the Mahler ‘Adagietto’ from his 5th Symphony. How can you beat that?”

Favorite piece to teach: “Oh, that’s hard. I think I could say the ballades—I love teaching the Renié’s Ballade Fantastique and Salzedo’s Ballade. I’m always happy to work on them with people because there is so much in each one of them.”

Favorite solo piece to play: “The one that I am currently working on. [Laughs] So right now it’s this Caroline Lizotte piece, La Madone. I’m just falling in love with it. And then I’ll learn something new, and that will be the one I’m in love with.”

Loman has followed through on all of her retirement plans she made. She’s currently working on a new album she hopes to release this spring. “I figure it’s a good thing to do in my mid-80s,” Loman says with a laugh. The album will feature pieces by harpist-composers that she has always wanted to learn, but never got around to, including the Tournier’s Sonatine, the Ballade Fantastique by Renié, Salzedo’s Variations on a Theme in Ancient Style (she’s never recorded the long version of the piece), and La Madone, a piece by Caroline Lizotte. “It’s a lullaby in a jazz trio style. I’m just so excited about it—it’s luscious; it’s really beautiful.”

She adds that the Tournier piece is quite difficult, which begs the question—what motivates an octogenarian with nothing left to prove to work so hard? “If you keep learning, you don’t stagnate,” Loman says. “If you keep teaching and playing the same things all the time, life is rather boring, for one thing, and there’s no challenge. Although, I must say, to play a piece like [Salzedo’s] Variations well, there’s always a challenge.” She goes on to point out that her performing has always given her many tools to pass on to her students. “Because of performing, I can give my students more from my experience than I would if I weren’t constantly performing and learning, which I still am.”

Teaching has always been important to Loman. Her first student 60 years ago was Erica Goodman—a Canadian harpist who has achieved international acclaim herself. “Erica was 10 and I was 22,” Loman recalls. “She was so musically talented and had such a fantastic aptitude that I didn’t have to do that much with her. I did have to teach her some technique. I was fresh from studying with Salzedo, so I used his method, but I don’t think either of us really use it anymore,” Loman says of Carlos Salzedo’s legendary harp technique. “When I was studying with Salzedo, he didn’t make me use his method. I just studied with him, and he made sure I got my fingers in and he taught me gestures, but I didn’t have to raise my elbows and scrunch my wrists in or anything, which is the way that most students are taught that method. Since Erica, though, I’ve had many students who have needed a lot of technical help, and I invented ways that would help them solidify their technique.”

For years Loman taught at her alma mater, the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, as well as the University of Toronto and the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, where she is still on the faculty. “I want to impart to my students the joy of playing music the way it should be played, but I can only do that if they have the chops to make it happen,” she says. “It’s always been my belief that a good technique is one of the most important things that a musician needs to impart any kind of a musical idea. Technique and control—if you don’t have those two things, it doesn’t matter how musical you are, nothing takes shape because you don’t have the tools to make them take shape.”

Few harp teachers have seen the number of students Loman has over six decades of teaching. Loman says the one big difference in the harp students she sees today compared to when she began teaching is the caliber of playing. “When I started teaching, the students would come to the harp from a different instrument at age 18 or 19, so they didn’t have that foundation that comes from [studying the instrument] when you’re very young and growing into it. Now kids do start early, and they do build a great technique over a period of time where it just becomes a part of them.”

Not only has Loman seen about everything there is to see in 60 years of teaching, she has also witnessed the evolution of the music business during that time. So what is her advice to young harpists? “There are so many wonderful harpists with nowhere to go. I’m just thinking about the Milwaukee [Symphony Orchestra] audition [held in the fall of 2019]. There were 70 harpists, and none of them got to the next round. That’s unheard of. I know how many really talented harpists there were there. I think harpists need to broaden their horizons and not only think of playing in an orchestra or just having a solo career or just having a teaching career. I think they have to be able to do it all. There are just so many harpists, and there aren’t that many jobs. Sometimes they’re going to have to be satisfied with not having an orchestra job, but being a darn good harpist and freelancing. You can change someone’s life playing for people in any capacity. If you teach, you have to care about every student and be diligent with their development, but also understand that there is more to teaching than just teaching the harp. You can really make a difference in a student’s life just by your attitude toward them and how you helped them.”

Loman says it’s not that she wants to discourage anyone from playing the harp, she just wants to stress the importance of a broad skill set for harpists today. “I have seen people who have done great in the music world. They are doing all sorts of things and making a good living, but they are really diverse in what they can do, and they are serious about it.”

When we interviewed Loman in 1996, she had long been a champion of new music—especially by Canadian composers. She continues to carry that torch for new music today. “I studied with Carlos Salzedo, and his main concern as a teacher and performer and composer was to increase the repertoire of the harp,” she explains. “He was constantly telling me and other students that we had to proselytize and get out there and get composers interested in the harp. I loved studying with him, so everything he told me was very important to me.”

Loman is pleased with many of the great pieces written for the harp in the last 25 years, and credits efforts of organizations such as the USA International Harp Competition, the International Harp Contest in Israel, and the American Harp Society in generating good new repertoire for the harp. Loman also notes that harpists who are arranging music written for other instruments for the harp are also adding a great deal to the repertoire. “I remember years ago when I was transcribing so many Scarlatti sonatas, no one else was doing it, and now everyone is doing it.”

Loman’s personal life has always been as full as her career. She and her husband, trumpeter Joseph Umbrico, raised four children. There’s an obvious question for someone who has managed to pull off one of the most prolific harp careers ever and have a family—how on earth did she do it? “Well, I’ve thought a lot about that question, and really, there’s a very short answer. You need a helpful husband, a good nanny, and a willingness to practice after they all go to bed. [Laughs] The other thing is that you just have to be willing to take 15 minutes to go through something if that’s all you have. I used to identify problem spots, and if I had 15 minutes with nothing happening, I’d go practice them.”

Loman says she’s received enough musical advice over the years to write a book. But the most helpful thing she has been told is to form a musical concept and use your ears to attain it. “No matter how much work you’ve done on your technique, your ear informs you on how that technique needs to be used or changed to create a certain sound,” she says. “Your technique is your default; it’s what you go to when you want to be solid. Your ear tells you, ‘Oh, let’s change this, let’s see if you can put your finger this way, or close your fingers in a different way.’ I learned that from many people, and it’s been quite valuable.” •

50 years of recording

A lot has changed in the recording industry since Judy Loman released her first self-titled album a half-century ago. The nearly 30 recordings she has released since 1969 make her one of the most recorded harpists of all time. Loman has featured music of many different genres and periods, but has always championed contemporary composers, especially the Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer. Promoting new works for harp is a value passed down to her by her teacher Carlos Salzedo, Loman told us in our 1996 interview with her. “…Salzedo instilled in me a sense of responsibility towards the harp repertoire, of trying to increase it as much as possible.”

1970—Make We Merry

1970—Make We Merry 1971—Judy Loman

1971—Judy Loman 1976—Folk Songs of the British Isles

1976—Folk Songs of the British Isles 1978—The Crown of Ariadne

1978—The Crown of Ariadne 1979—Sentiment

1979—Sentiment 1984—Dance of the Blessed Spirits

1984—Dance of the Blessed Spirits 1985—The Genius of Salzedo

1985—The Genius of Salzedo 1988—John Weinzweig: 15 Pieces for Harp

1988—John Weinzweig: 15 Pieces for Harp 1990—Dance of the Octopus

1990—Dance of the Octopus 1992—Adeste Fideles

1992—Adeste Fideles 1992—R. Murray Schafer: Concerti

1992—R. Murray Schafer: Concerti 1994—Meditations

1994—Meditations 1994—Music for Viola and Harp

1994—Music for Viola and Harp 1996—20th Century Masterworks for Harp

1996—20th Century Masterworks for Harp 1997—Chimera

1997—Chimera 1998—Ae Fond Kiss

1998—Ae Fond Kiss 1998—Dance of the Blessed Spirits

1998—Dance of the Blessed Spirits 2000—Harp Show Pieces

2000—Harp Show Pieces 2002—R. Murray Schafer: Patria

2002—R. Murray Schafer: Patria 2002—Favourites

2002—Favourites 2003—Illuminations

2003—Illuminations 2004—Musique de Chambre Française

2004—Musique de Chambre Française 2005—A Baroque Harp

2005—A Baroque Harp 2005—The Romantic Harp

2005—The Romantic Harp 2007—The Heavenly Harp

2007—The Heavenly Harp 2010—Lullabies and Carols for Christmas

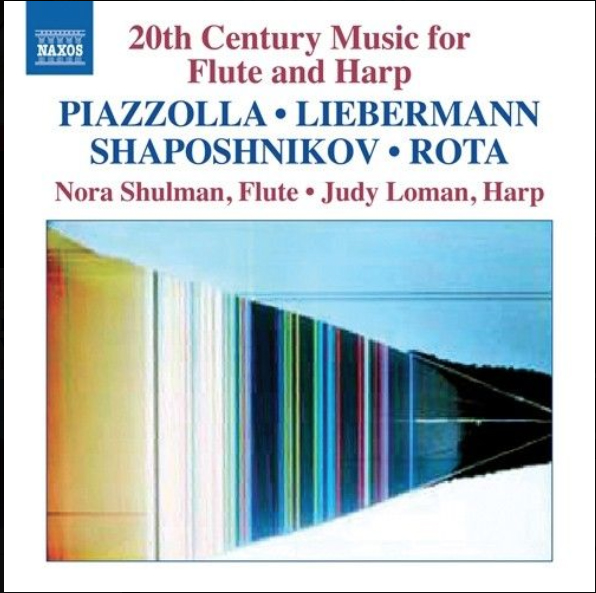

2010—Lullabies and Carols for Christmas 2014—20th Century Music for Flute and Harp

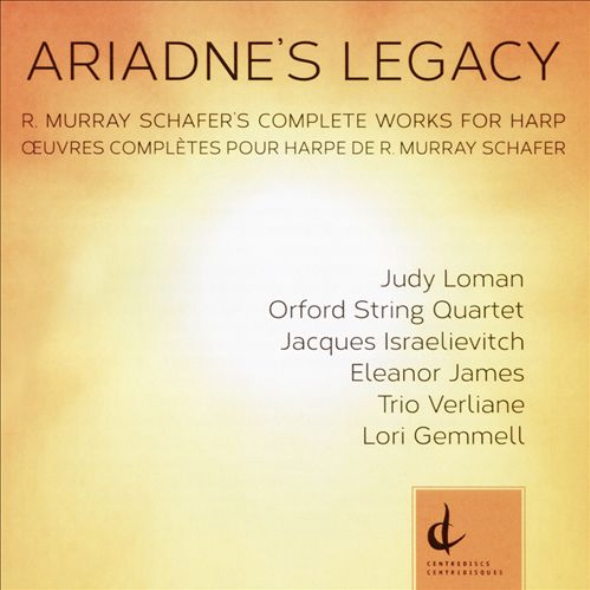

2014—20th Century Music for Flute and Harp 2016—Ariadne’s Legacy

2016—Ariadne’s Legacy