In 1990, the National Youth Orchestra of Canada selected two harpists for its summer session: Jennifer Swartz from Toronto and me from Quebec City. This was my first meeting with Jennifer. At the time, I had never spoken a word of English, and Jennifer had not spoken a word of French. In spite of that language barrier, the friendship between us began instantly and is still going strong 27 years later.

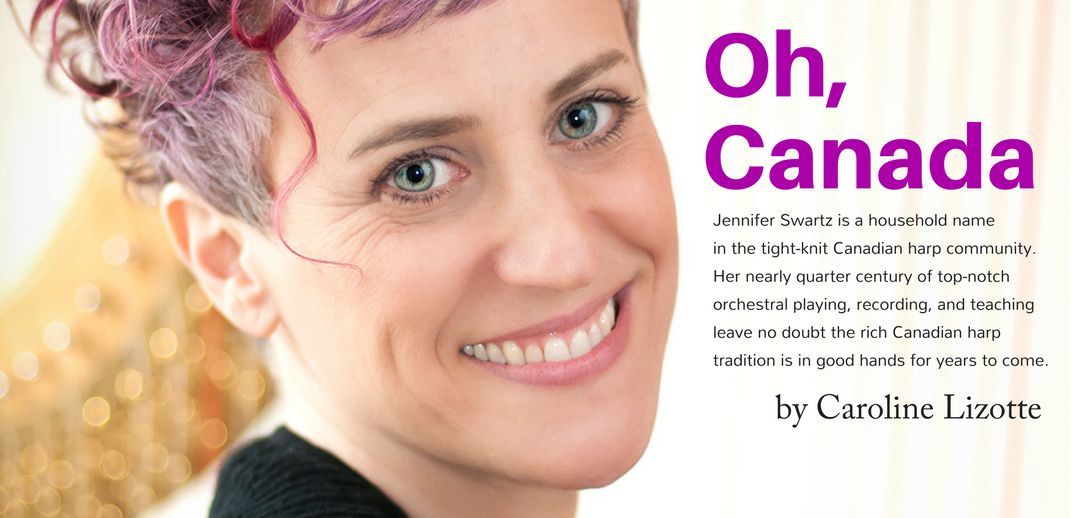

In 1994, Jennifer won the principal harp position with one of the most prestigious orchestras in North America—the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal (OSM). Over the last two decades, she has crafted a brilliant career as an orchestral harpist, soloist, chamber musician, and teacher. She is harp professor at the Schulich School of Music of McGill University, and her albums, recorded mainly by Atma Classique, reflect her best qualities as an artist and as a human being: supple, free, and limpid.

Under Jennifer’s fingers, any work becomes a gem. Her touch on the harp is exceptional, colorful, and has a rare sensitivity. For her, the harp is a way of being, a way of speaking. It is an immense honor for me to work with her as a second harpist at the OSM, as a member of the Four Seasons Harp Quartet, and also to collaborate with her as a composer.

Today, Jennifer speaks French Canadian fluently, and I speak fluently some sort of English. We have played almost the entire orchestra repertoire for two harps, and we have a lot of fun together. Amid our busy orchestral schedule this spring, we sat down for a conversation that I hope will let the harp world know this amazing artist as I do.

Harp Column: Could you tell us about your musical upbringing—both your teachers and your musical family—and how that shaped you?

Jennifer Swartz: I grew up in quite a musical family. I started playing music very young with parents who were quite encouraging of us exploring classical music. I guess having that around all the time just became part of my normal existence. When I was 8, I went away to an arts and music camp, Interlochen, which many of the readers may know about, in Michigan. It was there that I took a beginning harp class with Joan Holland. Joan was my first exposure to harp and to harp pedagogy, I would say. Even though I was a little girl, I really felt like Joan showed me how important the relationship between teacher and student is. She took me under her wing and treated me like her own daughter, like part of her own family. That continued as I came back and my mum was trying to find someone who would teach harp to me at that age. [My mother] reached out to the only person she could think of, which was the principal harpist of the Toronto Symphony at the time, Judy Loman. Judy never really took little kids to teach, but she had a student of hers that she liked to give students to—Maureen McKay. So I started with [McKay] at that point. But Judy was always in the background; she was always keeping an eye out. I would go and have lessons with her once a year for the first couple of years. Again, that idea of being part of something that was connected—the harp community—and to be brought in as part of that family was continued as Judy took me on as her own student. I was still young—I was only 10—and basically grew up with her. To answer your question as to how that shaped me, I think it profoundly shaped me to see music in a much bigger way—more than as an activity or a skill, but as a way of life. I saw learning music as a life philosophy, and being part of not just one but many different families and many different approaches.

HC: When you were young, is it true you learned to play the pedal harp with pedal extenders?

JS: Yes, that’s true. I was pretty tiny back in those days, and when I was ready to start playing on a pedal harp, I was too small. I think it was maybe even Mary Kay Waddington—though I’m not certain about this—who had created these pedal extenders. They were this crazy new thing you screwed onto the pedals. Now there are smaller harps with pedals, but back in those days, we were looking at large harps with pedals. So I would truck along to my lessons with my pedal extenders and clip them on. I would always need 10 minutes to get ready. [Laughs]

HC: It must have been funny, all that.

JS: They also wore out because the metal could get bent as you kind of aggressively played those pedals.

HC: How long did you study with Judy?

JS: When I was 10, I started with Judy full-time, and I studied with her up until I went away to study at Curtis. I had some other teachers at summer programs, but Judy was my teacher from age 10 to 18. Then I went away and studied for a couple of years at the Curtis Institute. And then I came back and continued with Judy for a couple more years. I still consider Judy to be my teacher, and I will always consider her to be my teacher.

HC: How did you decide between being a soloist and an orchestral harpist?

JS: In some ways, I think that it was decided for me. I grew up watching Judy have this career being the principal harpist for the Toronto Symphony, being a harp soloist on her own, being a chamber musician, doing recordings, commissioning works, having a family of four children, having a harp studio for teaching—this was my model. It didn’t really occur to me as a young person that I would be one or the other or anything. I think I held her up as an ideal, incredibly beautifully balanced life. I was really fortunate, quite young, to get my first placement in a professional orchestra, quite to my surprise. Things sort of just flowed from there. There wasn’t a point at which I thought, I’d rather be doing it differently. I was happy to follow what luck had in store for me. I’m still to this day very happy with basically not choosing. I guess in a way I’ve chosen—I think my orchestral career is the center of what I do, and there are things that flow from that because it is the most constant and steady work I have.

HC: You’ve been [with the orchestra] since 1994, so what age were you when you joined?

JS: I was 22 at the time, and I had come from one year working with the Calgary Philharmonic, which was my first experience getting my feet wet as a professional orchestral harpist.

HC: So you followed Judy’s model in playing with the orchestra for almost 25 years, but also being a recurring soloist with the orchestra, having a family life, teaching. What are the logistics of that like with such a demanding orchestra?

JS: It has, at times, been quite demanding. Year to year, life as an orchestral harpist can change quite a lot depending on the programming. My first years in the OSM with Charles Dutoit were very intense years, one, because I was still so very green. I was still learning the repertoire, learning how to do the job. But also, the repertoire of his taste really lent itself to a lot of harp playing. Other years, other seasons, sometimes with guest conductors, we all know that there’ll be concerts where things are a little lighter. So balancing that with, let’s say concerto work—which I did more of earlier in my career—is possible because you can find the holes in your schedule where this makes sense. But I think it’s always a balancing act, especially when you have a family, things change a lot as well. I’d say things just kind of ebb and flow. There have been periods where I’ve really pulled back from solo playing to have more time for family. As my kids are getting older now, I find myself coming back to personal projects that I had put on hold for the last few years.

HC: So you’re now a model yourself!

JS: [Laughs]

HC: You’ve played many, many concertos with the OSM under Charles Dutoit, Kent Nagano, and several guest conductors over the years. What is your favorite work for harp and orchestra?

JS: I always find favorite work, favorite composer a really tough question. This might sound a little corny, but I think when I’m doing a concerto, I’m in love with what I’m doing at the time. There are certainly some concertos that I find more effective than others, but in terms of performing and the experience when I’m in it, whether it’s the Debussy Danses or the Rodrigo Concerto or whatever else, that’s the favorite at the moment.

HC: Of the concertos that you’ve never played, which one would you be eager to do?

JS: Actually, it’s the one that you have written. So your Concerto Techno is at the top of my list.

HC: Oh my gosh! Really?

JS: Yes, in all honesty, this is something that I would love to learn and experience and perform some day. It’s certainly at the top of my list right now.

HC: Wow, it would be a very interesting project for the orchestra as well, because this one is difficult to book. We’ll work on that!

JS: We’ll make it happen!

HC: We’ll make it happen, of course! [Laughs] The OSM is among the most versatile Canadian orchestras in terms of what they play—they play everything. What are your favorite composers and favorite pieces when you are playing as a principal harpist?

JS: In general, what is most interesting as an orchestral harpist are those works where the composer really knows how to use the harp and its full color range, whether it is solely for coloration, or as a solo moment, or an accompaniment—I’m happy in all those roles. There are certain composers that really understand how to let the harp through the texture of an orchestra. It’s not necessarily a solo role; it’s an integral piece of the palette. I’m thinking obviously of composers like Ravel and Debussy. Mahler—unquestionably. Britten—amazing writing for harp. These are the kind of things that are extremely satisfying to play.

I think they are satisfying to play when there are two harps. We’re so often alone, and I love having harp parts that integrate well, that are almost duos in an of themselves, not just doubling so we have more volume, but parts that provide a musical interaction with fellow harpists within the orchestra. We can see that in the works of those composers I mentioned. Stravinsky as well, Bartok…I could go on. But the idea of how does the harp come through? What’s its role? There are certain composers that I think just understood that. I was just interviewed by a group for the OSM, and somebody asked me how does the harp, being such an interesting solo instrument, translate into being part of the orchestra. For me, they are very different roles, for the most part. We have moments of real virtuosic solo playing, but more than that, we are part of a bigger element. I think those composers that really help the harp be part of that bigger element are really inspiring.

HC: I know that you’ve been working closely with the OSM on the Manulife Competition.

JS: Yes, this Manulife Competition has been around for a really long time. It’s never actually had harp as one of the rotating groups of instruments. About 10 years ago, I encouraged the orchestra to add harp to its rotation. So far, we’ve had three editions that have included harp, and they’ve been really interesting and successful. We’ve brought in some wonderful international jury members. It is very exciting for our community here in Canada to have international harpists come through to not only be jury members for the competition, but also give masterclasses, and sometimes performances. We’ve taken a temporary step back from including harp, which speaks a bit to the nature of our small harp community in Canada. The harp community is always growing, and it’s unquestionably growing stronger. I think the orchestra needed to take some time to allow more critical mass to build to make the competition more interesting for the public. It’s a tricky situation. But we are very excitedly looking toward bringing this back very soon. I’m hoping to get the harp back on track for either every three years or every five to six years, to have the harp as part of this very important competition for Canadians.

HC: Yes, because there are not very many harp competitions in Canada, right?

JS: Specifically for harp, no. I think we have things at a lower level, but this competition really speaks to launching a professional career, so it’s for harpists or musicians who are really at that place, ready to jump into the professional sphere. It’s quite stringent, and there’s a very large list of repertoire. It’s very demanding, and I think it’s extremely important that we, in Canada, have harp included because I don’t think we have something like that here in Canada. So it’s very important to me that the OSM supports this idea.

HC: Thank you, because this is very important—the vision you had to include harp in this competition. So now it’s there; whether it’s three or five years, it exists.

JS: Yes, exactly. I agree.

HC: Can you tell us about the Canadian harp tradition—how do you feel connected to this Canadian harp tradition?

JS: I guess I would come back to my inspiration from Judy [Loman]. Judy is, and has been, such a champion of harp playing, harp technique, educating, and building relationships with composers writing for harp. I certainly can’t compare myself to her in any of those elements; I can only say I’m very inspired by her approach. So the way I feel connected, I would say primarily, is the umbilical cord with Judy. From there, it feels natural to reach out, show interest, try to help composers to understand the harp, and help the public understand the harp. While Canada is a very large country, we’re a very small harp community. I do feel we have a connection, whether we see each other at World Harp Congresses or events. We recently had a big celebration for Judy’s 80th birthday, and it was amazing to see harpists from across the country come and celebrate her and feel like we are all tied together in some way. So I really take my hat off to Judy for teaching that and inspiring all her students to feel like we are part of the Canadian fabric of classical music and contemporary music.

HC: So you see this tradition in Judy, and you are growing your own students in this same tradition?

JS: I hope so. I certainly think one of the things about tradition and innovation is staying open to other teachers, other approaches, other harpists, other musicians we have access to. All of this slowly but surely changes the direction of tradition or what is happening in the harp world technically. One thing that is particularly important to me is the body. There was a time when we emphasized more the doing, as opposed to how the body does it. To me that’s another piece that shapes how I see harp technique—how we use our body, understanding the physiology of using our muscles, what works and what doesn’t, and finding that in harp technique tradition. There’s no room to hold on to one thing because this is the way it’s supposed to be done or this is the way it always was done. So I see that evolution as a personal project—being always open to discovering how we can make it easier and how we can make more with less effort ,to let the music come through.

HC: That comes from a more global way of thinking, not just holding your fingers as French or Salzedo technique.

JS: It’s interesting as a teacher. Having students who come from a variety of different backgrounds and technical foundations is an amazing educational experience. You end up working with what they have, as you so nicely put it, from a global approach.

HC: Tell us about your teaching studio.

JS: My primary teaching is with McGill University. I’ve been there as long as I’ve been in Montreal. I’ve had some really wonderful experiences with the Youth Orchestra of the Americas, traveling to amazing places and coaching as part of the orchestral faculty team. I do some private teaching, but I try to save my summer time for family time. I’ve hosted private, more personal harp camps at my own home, and that’s something I’d like to do more of. Now that my kids are getting older, I can see having more space to develop new workshops.

HC: As one of the most supple-minded and versatile harpists, as well as an eccentric and brilliant interpreter, what should change or evolve, and what should stay traditional in our harp world?

JS: I had the opportunity this year to be a witness to what is actually happening in the harp world—from the most traditional to the most innovative. I’m speaking of getting the opportunity to hear one of your students perform her final master’s recital in the most incredibly technologically inspiring directions. One of my own students did one of his final recitals going back in tradition, which is kind of a trend right now, going back to early harps and being able to get around technically—going backwards in time, but also going forward in time. I can see that things are changing, but I don’t know if it needs to change; it’s just naturally evolving. Everyone is doing more than just one thing. We’re always looking to see how we can move into other areas, whether it’s by exploring harp playing from different time periods, new kinds of harps, or performances involving other art forms. I don’t know that I can put my finger on something I think should change. I see things already changing to be more inclusive, more open, and wider.

HC: That’s interesting. So, we’re coming out of an era of Baroque transcriptions that were often too rich or too Romantic, and we’re naturally returning to the essence of the music as it was written.

JS: I agree. I think we are looking less at other people’s transcriptions, and instead working on our transcriptions, working on our own versions, coming back to—particularly with earlier music—original texts. We’re having the musical and intellectual and technical freedom to put our own touch on it. While other people’s transcriptions, particularly in the harp tradition, are always so informative and educational and interesting, I think students and performers today are putting their own personal stamp on [their repertoire], as it should be. I think it makes this music always contemporary and always alive.

HC: Working with you and Judy Loman on the creation of Raga for two harps, in fact this was dedicated to you both. I remember how fun it was because I had the certainty that everything was allowed—virtuosity and interaction between extended effects and normal playing. Tell us about working with other composers in writing new works for the harp. How do you go about it?

JS: Working with you, it was just a pleasure to see your amazing creation. You, being a harpist, had the full range of vocabulary and then some. As a composer, you are always pulling into the future and into your imagination, what is possible on the harp. Being a harpist is such an advantage. This is a bit of a boring answer to your question, but in working with composers who are not harpists, a lot of the time spent is just helping them understand what the harp can do. I think some composers who are not harpists can be quite intimidated. “It can be an intimidating discussion or an intimidating project, so I should just stay away from it.” I know that I’ve heard that story many times from people who, before they worked with Judy, felt ill-equipped just because the harp can be a bit daunting. So I think the first step is just understanding the instrument. And second is the license for freedom, to not feel confined to what it appears the harp can do.

HC: So you would suggest cultivating good musical relationships with the composers and working closely with them.

JS: Absolutely. You should develop that connection, but then it’s also important to leave the composer alone with the harp. They should have the chance to conduct their own exploration and to see what sounds and ideas are possible. That can help them get away from traditional notions of what the harp sounds like.

HC: It’s going there…

JS: Unquestionably.

HC: One thing I know about you is that you pick things up very quickly. You’re well-versed in many fields. You’re very spontaneous. You’re open to learning to scuba dive, dance, cooking, design, languages. Is there an unexplored world that captivates you that you’d like to jump into?

JS: I’m sure that I’m going to keep exploring things I haven’t tried before. I’m definitely interested in mixing harp with some of my other interests, maybe not scuba diving so much, but particularly dancing and theater. Both of those areas have been a passion. I haven’t found exactly what I want to do, but it’s something that I could see pursuing further down the road.

HC: What do you want to accomplish next?

JS: What I am very excited about is something on a pedagogical front. I’ve just recently created a quasi-performance space in my home, and I’m very excited about the potential this could have for up-and-coming harpists and other musicians as a safe, fun, warm environment to practice performing. We never get enough opportunities as harp students to be on stage, to experience what it is like to be a true performer and interact with the public in a warm environment. I think more and more people are interested in experiencing music this way. At this point, I wouldn’t quite call it a concert series yet, but something moving in that direction. I’m very excited to be able to offer this opportunity to young musicians and also seasoned players who are looking for an opportunity to share their music, share something new they are working on in this space.

HC: That’s important, and I like how it brings together the Montreal harpists circle, and maybe beyond. What’s next in your agenda?

JS: I’ve just come off a big project with our concert master Andrew Wan with the Montreal Symphony. We just finished doing a really nice program where I transcribed or arranged some great music by composers we don’t have writing for harp. There are a few projects on the horizon, but I’m mostly looking forward to enjoying a Montreal summer, relaxing a little bit with my girls, and getting excited for new students coming in next year. It’s interesting, I find I don’t need or desire to have too many projects lined up just so that I have the space to touch all the aspects of my life. But there is always something on the horizon.

HC: That’s great. Thank you so much, Jennifer! •