Ed.—find out why our author is Hearing a Call to a New Profession in this article extra.

Ask any harpist which of their five sense they value most, and their answer will likely be hearing. But how much do you know about your hearing, and what are you doing to preserve and protect it? Many musicians have a disconnect between the value they place on their hearing and their understanding and protection of this critical sense. With a foot in both the music world and the audiology world, I’m going to help you make sense of your most valuable sense.

First, let’s take a look at how our hearing works. Hearing actually happens in the brain. Sound must travel through the ear up a complex path to the auditory cortex, the area of the brain where hearing occurs. The ear is divided into three parts (see figure 1). The outer ear includes the pinna (the skin-covered cartilage on the outside of your head that is the “ear” we see), the ear canal, and ear drum, or tympanic membrane. The pinna acts as a funnel and captures the sound in the air, sending it down the canal to vibrate the eardrum, a membrane that divides the outer from the middle ear. On the other side of the eardrum is the middle ear, an air-filled space when healthy (fluid from illness or allergies in the middle ear is a common problem but that’s for another column). Inside the middle ear are the three smallest bones in the human body, all of which would fit on one dime: the malleus (hammer), the incus (anvil), and the stapes (stirrup). When sound hits the eardrum, these bones are vibrated in a chain reaction that pushes on a small window on the cochlea, or inner ear. This snail shaped bone is filled with fluid and houses a membrane that conveys information about loudness and frequency, or pitch, to the auditory nerve, which in turn carries this information to the brain, where we perceive sound. Inside the cochlea are lots of tiny hair cells that vibrate and move with the fluid when sound comes into the ear. These are particularly important when talking about noise-induced hearing loss.

Understanding hearing loss

Hearing loss can occur in many different ways, but we are going to focus on noise. Noise-induced hearing loss is a form of sensorineural hearing loss, or loss that occurs in the inner ear. This is different from a hearing loss caused by fluid in the middle ear, such as an ear infection, to go back to our earlier example. When loud sounds come into the ear, the hair cells in the inner ear can be damaged, inflamed, or even die. This can occur with a single occurrence of a sound that is too loud. At first, the hair cells mostly recover, and while you may notice some temporary symptoms (like ringing or roaring in the ears, a feeling of aural fullness or being “stuffed up,” or fatigue), after a while, things seemingly go back to normal. Unfortunately, temporary hearing loss can add up over time and eventually become permanent. Hair cells in the cochlea can be permanently damaged or die; they do not regenerate and cannot be cured or replaced. While it is true that some people are more genetically prone to hearing loss than others, enough noise exposure can cause a hearing loss that cannot be reversed by medication, surgery, or other treatments. Once hearing is lost in this way, it is gone forever.

Symptoms of hearing loss

What can hearing loss look like for musicians? Well, like anyone else, the first symptoms are often struggling to understand others in background noise, such as in a noisy restaurant. It might sound like everyone is mumbling, or perhaps women and children’s voices are harder to understand. This is related to high-frequency hearing loss. Higher frequencies, or pitches, tend to be affected by hearing loss first, because of the anatomy of the inner ear. The area that codes these sounds is closest to the outside, so it bears the brunt of the noise and is therefore damaged first. The higher frequencies in human speech are the consonant sounds that give speech its clarity. So, you may be able to hear the volume of someone’s voice, but lack the clarity, or understanding of what they are saying.

Another common symptom of hearing loss is tinnitus, or the perception of sounds that are not physically present. Commonly called “ringing in the ears,” the sound can be almost anything: buzzing, static, crickets, bells, roaring, etc. Tinnitus can occur after being exposed to loud noise, or can be a frequent or constant symptom of or precursor to hearing loss. A less commonly known condition is diplacusis, a disorder related to pitch matching that ultimately results in certain notes sounding flat; or hyperacusis, which is an extreme sensitivity to loud sounds, wherein common sounds such as normal conversation or a telephone ringing can seem intolerably loud. In addition to these symptoms, musicians may notice more difficulty distinguishing between pitches or perceiving pitch across the full spectrum of sound. They are more likely to struggle with distinguishing different timbres, and balance among different instruments may seem distorted. As harpists, we rely on excellent pitch discrimination abilities, allowing us to tune our instruments quickly and frequently, being able to pick out which string is out of tune during practice or a performance and quickly adjust it by ear, often without the use of a digital tuner. If struggling to hear your friend at a loud restaurant sounds like an annoying inconvenience, imagine the nightmare of losing the ability to tune your harp or balance your students’ harp ensemble, appreciate the nuances in chamber music, or soak in the glory of a symphony orchestra. It is not an exaggeration to say that any of these conditions could be potentially career-ending in extreme situations for musicians. Neither sensorineural hearing loss nor any of the other disorders mentioned above can be cured; therefore, hearing protection and prevention of noise-induced hearing loss is the best, and only, course of action.

Coming to your senses

Plugged in

You can get custom musicians’ earplugs from an audiologist. To find one in your area, visit www.audiology.org.

We probably all have had an experience with our hearing that made us stop and think, “Uh-oh.” We have all been in situations that we know are too loud. Sometimes we are aware of what is happening, and sometimes we only realize it in retrospect. My “come to Jesus” (come to ear plugs?) moment happened while playing a Maslanka wind symphony with a huge, Texas-sized wind ensemble. Being on stage was physically painful at times due to the sheer number of instruments and extreme volume level. I dutifully put foam ear plugs in, but only after I was done playing my part, because I felt I could not risk a dampened awareness of what my colleagues were doing. Even with ear plugs, my ears felt full or stopped up, voices sounded like they were in a tunnel, and my ears rang for hours after the rehearsals and concerts. I would say things like “I always wear ear plugs in rehearsal but I can’t perform with them.” Little did I know then the risk I was taking with my hearing. And plenty of the other musicians (and the conductor, taking in the full blast front on) in that concert didn’t wear ear plugs at all.

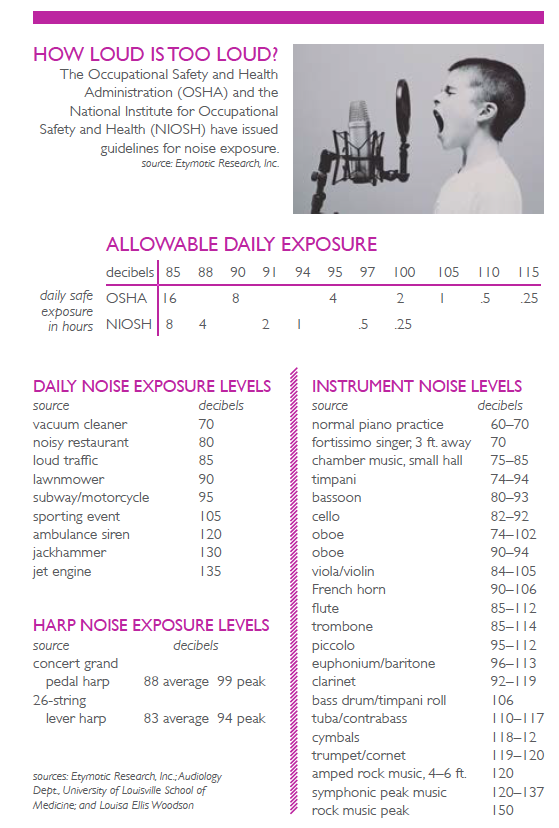

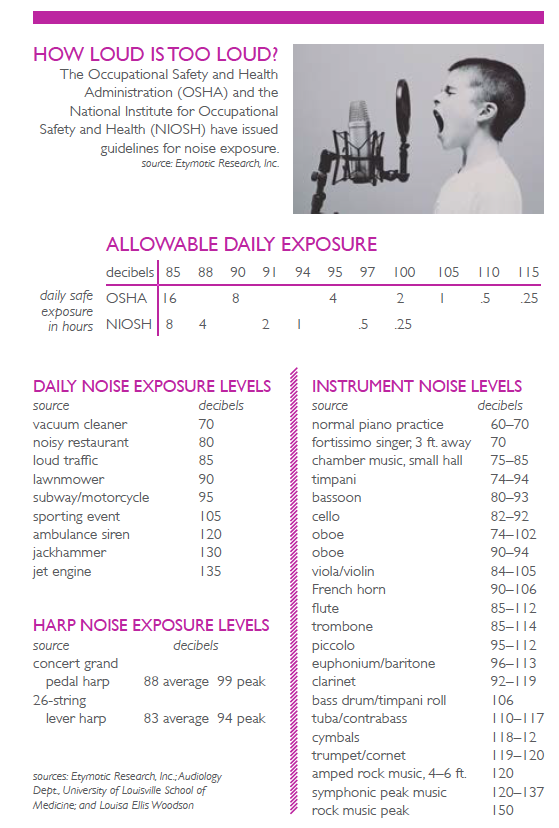

To understand risks for hearing loss and how to counteract these risks, we need to understand a little bit more about loudness. Loudness or volume is measured in decibels (dB). To give an idea of what measured decibels sound like, rustling leaves in the wind produce a sound of approximately 5 dB, and a whisper is around 20 dB. Normal conversational speech is around 55-60 dB, and a vacuum cleaner is about 70 dB. A lawn mower and a motorcycle are around 100-110 dB, and a concert or sporting event is around 110 dB. A jet engine is about 120-130 dB from 100 meters away. Physical pain and instantaneous damage to human ears is usually caused around 140 dB.

A general guideline to keep in mind is the “three-foot rule,” meaning that if you have to raise your voice to be heard from a distance of about three feet away, the environment is likely too loud. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has issued more specific guidelines for noise exposure. Employers are required by law to comply with OSHA standards, which is why today, loud workplaces like airports and factories, for example, may require hearing protection. According to OSHA, a person can be safely exposed to sound at 90 dB for eight hours in one day. Every time that level is raised by 5 dB, the safe exposure time is cut in half. A sound at 115 dB, an average level for sporting events or concerts, is dangerous to the ear after only 15 minutes. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), which does not have to account for economic factors like OSHA does, puts the safe level of exposure for eight hours at a more conservative 85 dB.

Hearing on a different level

So what about musicians? First of all, if you are reading this, congratulations on your superior musician’s brain. Studies have shown musicians to have better than average auditory perception. Many people are familiar with the “Mozart effect,” which hypothesizes that mere exposure to classical music can improve mental development in children. Musical training and practice increase spontaneous attention to sound and sound discrimination abilities. In the last 20 years, brain imaging studies have revealed that musical training has dramatic effects on the brain. Increases in gray matter (size and number of nerve cells) are seen, for example, in the auditory, motor, and visual spatial areas of the cerebral cortex of musicians. As Dr. Oliver Sacks writes in his book Musicophilia, “Anatomists would be hard put to identify the brain of a visual artist, a writer, or a mathematician—but they could recognize the brain of a professional musician without a moment’s hesitation.” So this is obviously great news for us musicians; however, musicians are also much more sensitive to changes in their hearing. In other words, a mild hearing loss that may not bother the average person, or even appear to be significant on a hearing test, can feel catastrophic to a musician.

For rock musicians, noise induced hearing loss seems an obvious consequence. For classical musicians, the studies are less conclusive. Classical musicians are much more likely to have long hours of exposure outside of only an orchestra rehearsal, for example. One study with the Chicago Symphony found that results varied based on repertoire being performed and by seating and proximity to other instruments, but on average, at least some musicians were meeting or exceeding the recommended 85 dB noise dose from their orchestral jobs alone. In orchestral rehearsing alone, the harpist’s peak noise exposure was around 86 dB, (along with cello, bass, and piano). These measurements represented an average over two different weeks of rehearsing, several months apart. A separate study of 329 music students, aged 18-22, including vocalists, brass, wind, string, keyboard, and percussion players, found that 45 percent had a noise notch (a pattern on a hearing test commonly found with noise-induced hearing loss), and hearing loss was present across all groups.

You can infer that once individual practice, outside gigs, teaching, and any additional playing are factored in, musicians are very likely being exposed to more loud level noise than is safe. There is also the issue of sudden, extreme impact noise (a high point in volume that may not last long but is loud enough to do some damage on its own). While an “average” level of a concert or rehearsal may not be extreme, at least one of these impact noises at a climactic moment is quite likely. Nearly every concert has a high point. During a recent performance cycle I played with the Louisville Orchestra, a peak level of 102 dB (average: 86 dB) was measured on a free iPhone sound level meter app, just while sitting on stage during two pieces, for a total of about 30 minutes. Additionally, I was seated behind the directional wind and brass instruments, and away from the bulk of the percussion, so this reading is probably lower than the actual peak.

Hear are your options

The simplest general advice is to avoid or leave a situation when it is too loud. Obviously, this is not always a practical option. Sometimes, baffles or sound barriers can be used, or seats can be changed (so a trumpet is not pointing directly at your ear, for example). Occasionally, volume can be adjusted. In rehearsal and performance situations, however, these remedies are often impossible. The best option then becomes something the harpist can wear to protect the ear without compromising the ability to hear.

Many over the counter ear plugs are available, and often, simple foam ear plugs are provided at rehearsals. While these are better than nothing, there are some problems. The ear plugs are intended to seal within the ear canal and prevent loud sounds from passing through. First of all, many people do not wear these earplugs properly, which significantly reduces their effectiveness and the amount of sound that is attenuated (or reduced). All ear plugs will have a Noise Reduction Rating (NRR), a scale that indicates how much of a reduction in sound level (in dB) is possible. Be aware that NRR does not equal dB (an NRR of 33, for example, actually reduces the sound level by 13 dB). However, if the plugs are not worn properly, the protection provided will be significantly less than the indicated NRR which was calculated in a carefully controlled lab, and even when used correctly, the real-world NRR is usually less than marked. If an ear plug is visible when looking straight on from the front, the plugs are likely not inserted deep enough into the ear canal. Some plugs simply do not fit an individual’s ears correctly. Ear canals are rarely straight cylinders and have many twists, turns, and angles.

The second problem with these ear plugs is that they can distort and change the sound, which can be disorienting and distracting in a performance situation. Foam ear plugs tend to reduce the higher frequencies more than lower, which can cause sounds to seem muffled. These plugs can also produce what is called the occlusion effect. This is the reason your own voice sounds echoey or louder when you plug your ears with your fingers. This can further distort the sound by making the bass frequencies disproportionately louder.

Earplugs that are geared toward musicians’ needs provide what is called a “flat frequency response,” reducing all frequencies equally. This preserves the soundscape more faithfully, just at a safer level. Many musicians’ ear plugs are commercially available, some over the counter. These typically come in two different sizes and at varying NRR levels. Others can be custom made by an audiologist. These are going to have the best fit, ensuring comfort but also an adequate physical seal and therefore appropriate protection. An impression of the ear canal is made by the audiologist, which is then sent to one of several manufacturers who make an earplug exactly fit to the individual’s ear size and shape. The depth of the impression reaches beyond the depth of an over-the-counter plug to the bony portion of the ear canal, which eliminates the occlusion effect, reducing the enhanced bass or echo. Many types are available, including some with interchangeable filters that can vary the attenuation, or reduction, of the sound level. Commonly available filters offer attenuation of 9, 15, and 25 dB. High end models can include in-ear monitors or even automatically adjust attenuation. Basic custom musicians’ plugs typically cost $175-300. To put that into perspective, a pair of hearing aids is around $3,000–$7,000, and typically not covered by insurance. While not inexpensive, custom musicians’ plugs are a good financial investment when you consider the alternative you’re likely to face down the road.

For harpists, particularly in orchestra, the main danger of noise exposure comes not from our own instrument, but from our colleagues near us. Typically, the harp is in front of the percussion, to the side of the winds, or occasionally near the brass. The dangers from percussion seem obvious; other instruments though can be very loud and directional. That piccolo to your left is aiming right at your ear. Not an orchestral player? You might practice in a small, reverberant room with hard surfaces that let that sound bounce around for a long time. Perhaps you play in a noisy restaurant a few times per week. Maybe you’re cooler than me and play with a jazz combo or rock band or some other group that uses amplifiers. Maybe you just like to go hear your friends play in their loud bands. Even if you do not always need significant noise reduction, having the option available is always a good idea, because occasionally we all find ourselves in situations that are too loud. There’s always that summer pops concert with the actual cannons for the 1812 Overture. Even when you’re not playing the harp, you still should to protect your hearing at a loud bar, a concert, while mowing your lawn, etc. And if you’re not sure if the environment you’re in is too loud, you can always use the three-foot rule, or utilize a number of sound level meter apps that are available on your smartphone to measure the noise around you.

As an audiologist, I am a big fan of hearing aids. If you already struggle with hearing loss, due to noise exposure or something else, I would encourage you to see an audiologist because there is amazing help available, and although audiology is a relatively new profession, we are experts in the field of hearing and are best equipped to help with hearing loss, balance issues, tinnitus, and much more. The technology has advanced by leaps and bounds, and for many people can be life-changing in the best way. However, as a musician, trust me when I say you do not want them if you can avoid them. Nothing can replace your natural hearing, especially to the superior, particular, nuanced, discriminating musician’s brain. It is far better to protect the hearing you have rather than try to correct the damage with a device. Even the best, top of the line hearing aid is just that: an aid, not a cure. And not to scare you, but tinnitus, diplacusis, and hyperacusis can be even more difficult to treat than hearing loss.

You must protect your hearing like the important tool for your craft that it is. To quote Bernard Andres, “As a musician, you have to think that your main instrument is your ear.” You would never willingly expose your instrument to irreversible damage over time. We all move our harps carefully, ensure the temperature and humidity are just right, dust them, cover them, tune them, and have them regulated. Why then would you expose your greatest asset, right there in your own head, to permanent harm that is preventable? You have a finite number of tiny hair cells in your ear that once damaged, cannot be replaced, unlike a broken string. Hearing happens in your superior musician’s brain, and taking a few precautions in loud situations will increase the odds that you can hear your own music as long as you want to make it. •