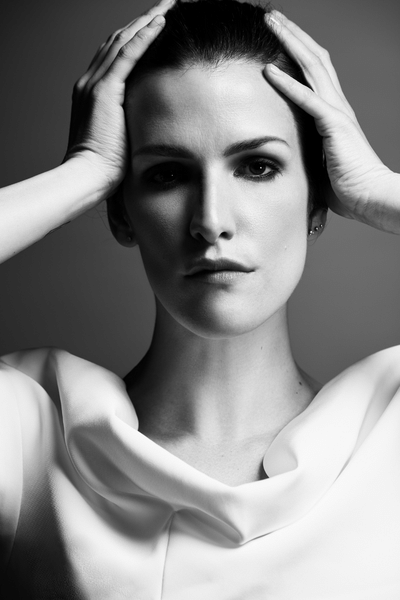

Most experts will tell you that one of the keys to finding success and longevity in a pursuit is being able to define your “why.” That’s the reason major businesses and organizations give so much thought and attention to writing a mission statement and pursuing it with laser-like focus. If you are wondering what a mission-driven harp career might look like, we present to you exhibit A: Valérie Milot. Like most freelance musicians, Milot wears many hats. She is a performer, of course, mostly solo and chamber music these days, as she has become too busy to do much orchestral playing any more. She is also an entrepreneur, producer, teacher (at the Montreal Conservatory), and recording artist. With so much on your plate, it could be easy to lose sight of what you are producing shows, teaching classes, and schlepping your harp around in the Canadian cold to play a grueling concert schedule. But Milot has given a lot of thought to her purpose and takes care to pursue it with the same authenticity that originally drew her to the harp. We caught up with Milot via Zoom on a cold and snowy January morning right before she was heading out into the Quebec winter for a two-week tour.

Harp Column: Your music first appeared on our radar through your recordings—both video and CDs—which have been reviewed in Harp Column. You’ve recorded a wide array of music—from the standards of the classical harp repertoire to transcriptions of major orchestral works. How do you choose what to record?

Valérie Milot: It really depends on where I am in my life. I think your first recording is always the most stressful repertoire-wise because your first recording is a sort of expression of who you are as a musician. [When I made my first recording] I was just getting out of school with my master’s degree, and so I commissioned a piece from Caroline Lizotte called La Madone, which is played a lot today, and I’m very happy about that. I think the repertoire I choose depends a lot on my encounters and my touring. It’s been almost 15 years since I started recording albums, and the market has changed a lot, and the purpose of recording has also changed a little bit. We all know that people don’t really buy CDs anymore. Recordings are much more about online streaming. In the big scheme of things, there was a short little period of time in which people were buying CDs, and musicians were making money from selling those CD recordings because you could not access music on the internet. I think that time is over now, and we need to see recordings almost like business cards. I see [recordings] like a derived product of my tours. Often when I record a CD, it’s because I will be touring this music on stage, and the CD is something that people can take home to have as a souvenir of the show. This is how I see [records] now—more like it’s done in the pop or rock music business. And I think it’s much more logical this way. I do have the dream of being able to record just because I want to explore something, but my reality is that I have to make a living from playing on stage. So for now, recording is more like an accessory to my tours.

HC: You talk about making a living on stage, and you’re about to head out for a concert tour this afternoon. Tell us about what daily life looks like for you when you’re on the road.

VM: It’s very busy, which is surprising because during the pandemic, it was like a desert. Here in Quebec, everything has gone back to normal, but now even more than normal. I’m doing over 25 concerts in the next five weeks. This is a lot, maybe a bit too much, but I’m very happy about it, and I feel very lucky to play that much. I tour a lot in Quebec, but usually it’s a short distance from Montreal, so I can go back and forth. The tour I’m leaving now for is a bit more than two weeks, and we are going through northern Quebec. I would say that this year is not quite normal compared to what my life was like before the pandemic. But I think a musician’s life is all about unpredictable things, and we have to get used to it and try to adapt to it. I do teach, but the way I earn my living is really by playing concerts and producing my concerts too, because I’m also a producer.

Quick questions for the Quebecois

Coffee or tea? Coffee.

Favorite app? TikTok.

Hidden talent? I can do fantastic braids in my daughter’s hair.

Best part of living in Quebec? The people.

Favorite piece to play on the harp? I would say Britten’s Suite.

Favorite place you’ve visited for work or for pleasure? Paris.

Favorite footwear at the harp? Heels.

Early bird or a night owl? I’m a very unpredictable mix of both.

Hardest technical thing for you to do on the harp? I think it’s trills.

Last album that you listened to? It’s an album called Nuit Blanche by two pianists from Quebec called Duo Fortin-Poirier.

What would you do for a living if you didn’t play the harp? I think I would have listened to my parents, and I would be a doctor.

One thing you always have with you on tour? Well, that’s funny. I would say a humidifier, not just for the harp, but for me too because winter in Quebec can be so dry.

What kind of harpmobile do you drive? I have a Toyota Sienna.

What was your luckiest moment in life? When my daughter was born.

What is the most underrated part of being a harpist? It’s hard to say. I always go back to its sensuality—when you play you get these very intense vibrations you can feel. To me, it’s addictive. I think people who don’t play the harp don’t really realize it. But when you play the harp, you know.

HC: I noticed in your press materials, you refer to yourself as “a musician and an entrepreneur.” Tell us about your production business and the two companies you have.

VM: Yes—they are a big part of my life. In 2016, I started a production business named Anémone 47, which is basically a production and touring company, and now it has evolved into a charity company with a mission of bringing music to people. I produce the show, and then I take the show on tour. I have employees and people I have to manage. It’s a lot of time, a lot of hours doing paperwork and making sure that everybody is doing okay and trying to fix things. That’s why I really see myself as an entrepreneur—the business side of my career is not about playing the harp, really. It’s just about organizing things so I can play the harp in my productions. But I was not really thinking about [producing shows] at the beginning of my career; it just appeared logical for me to do. I guess it’s because I like to have a certain control of what I do. And also, as we all know, when you play the harp, there is no path to follow. You often have to create your own occasions. Since I wanted to play on stage a lot, I decided to create my own business and make the occasions appear the way I wanted. It was a lot of work to start this company, but now it works very well. We have a lot of tours and we also have a little harp series at the Conservatory of Montreal where I can invite other harpists. And I’m starting to produce shows in which there is a harp where I don’t play. So I’m very happy about it and about the mission that the company has.

HC: I think that what you say about creating your own path because there might not be one to follow or one that you want to follow will resonate with a lot of harpists.

VM: Yes, I think most harpists can relate to this. We always hear that the harp should be a certain way. I felt that from the beginning, even when I was a student. But I’m very, very stubborn, and I try to do things my way.

HC: Do you think that you, in the music you perform and in the productions you create, are intentional about contrasting the idea of a stereotypical harpist? Is it something you intentionally try to push against? Or are you just you?

VM: I think it’s just about being myself because I do embrace any type of harp or a harpist, and I think every different aspect of the harp playing has its own place in this world. I started my career playing in big gowns and all that, but I was just not comfortable at all. So one day I was working with an agent, and we were working on my image, trying to define what I am. I think it’s an important exercise to do when you spend all your life playing on stage, sharing what you have to say and trying to connect with people. You have to be very convinced about who you are. And [what you wear on stage] is just one aspect of it that can sound so superficial, but it did make a big difference. Now I perform all the time wearing pants instead of gowns because I just feel I’m much more myself this way. I do appreciate seeing a harpist play in a beautiful gown if they want to rock it. It’s just not me. Also, I feel that sometimes people have a preconceived idea about the harp, but the harp is, in fact, much richer than what they think. Yes, it can be heavenly and ethereal, and I do like those moments too. But there is also a very intense and powerful aspect of the harp, and I like to play with both. You know, it’s what made me fall in love with the harp. The fact that it appears to be so light, but in fact, when you play it, it’s very intense. The strings are very tense and you have to involve your whole body in it. So I like to open doors for people that would maybe not be interested in going to the harp concert because they think it would be too light and ethereal, but find out it’s that, but also much more.

HC: Recently you had a lot to say on your Facebook page about an article that appeared in the press in Quebec about the lack of accessibility to classical music. There’s a lot to unpack there, but let’s start by having you tell our readers what your response is to people who say that classical music—maybe even all music that isn’t pop music—isn’t accessible to the general public.

VM: Yes, I was talking about mission. It’s something that is very important in my life, not a self-centered mission, but a mission about the harp and making it more accessible. It’s very important to me. But it’s also applicable to the classical music world because I think it’s the same. I feel that I was privileged to have access to the harp, to have access to classical music concerts, because that’s how I became interested in music. My parents were bringing us to our hometown orchestra. We had season tickets, and even though I didn’t always want to go [Laughs], I was at every concert, and I could see the harp often. The harpist in that orchestra was actually Caroline Lizotte, who was my teacher much later, and who I call my harp mom now. So I had access to that because my parents encouraged this culture of having access to art. This isn’t about money, though there is definitely a money aspect, it’s about being rich in your head. I come from a family where everyone worked in healthcare. My father was a bone surgeon, my mother was a respiratory therapist in surgery rooms, and my sister and my brother, they work in a more social aspect of healthcare—equality and social medicine. So this idea of giving the same chance to everyone is very strong in my family. I am very aware that if you come from a wealthy and healthy family, that you will have access to many things. But it’s really a matter of chance into which family you are born. If you are born in a poor family or if your parents are not in your life or you have difficult family circumstances, then you don’t have the same chance as others. Here in Canada, we do have very good programs to give people access to culture, and we are very organized for that. But there is a big, big gap in the general access to it. These programs exist, but almost no one talks about them because they are not lucrative so they don’t get attention.

HC: So these programs that make art widely available are only seen as valuable to the point that they can make money?

VM: Yes. When we give a lot of attention to shows like, in America, you have America’s Got Talent, we have those shows here too. These shows produce superstars who then go on the talk shows and variety shows, and all this attention is given to very few people. Meanwhile, all this great art and culture, which is at least as valuable, if not more, is pushed aside because it is not lucrative. Having a symphony orchestra is not lucrative at all—it cannot be. Having 80 musicians on stage to play Mahler is not lucrative—it cannot be. But that doesn’t mean that people cannot have access to it. So this article I was criticizing was just the result of a lot of mistakes we made over the past decades—closing music programs in schools and restricting access to art. I think we should be doing the opposite—we should have people talking about art and culture on the TV and have free access to culture rather than having this wall between great art and culture and people.

HC: What would you say are the biggest myths about classical music and classical art forms?

VM: There are a lot, but the biggest myth about classical music is that it has to be democratized. Because saying that means that it is accessible only to the elite, which it is not because by definition, classical music is accessible music. It’s music created by the people to be played by the people to be listened to by the people. To me, it’s simply pure music. Some musicians think that [classical music] has to be explained, and you will have a greater experience if you know about what you are listening to. But it depends on the way you appreciate things. For example, you can drink a very good wine and have a blissful experience. And you can drink that same wine and know the language to describe it and put words to it, and then you can have wonderful conversations about the wine. But the first impression is the same in both cases. You just have this wonderful moment in your mouth. So I think that music should be the same thing. It doesn’t have to be explained, it doesn’t have to be democratized, it just has to be accessible.

HC: That’s a good analogy.

VM: You should not need to have any specific education to love your experience with a piece of music. We artists have things to think about in this regard, but also, I think institutions and the media have things to think about in terms of their mission of sharing culture.

HC: I have two questions to follow up with that. As musicians, what do you think our individual responsibility is to our art form? And what do you think institutions’ responsibilities should be to the art form?

VM: I think as an artist, your only responsibilities are to be yourself and be as accessible as possible. The world just needs pure artists who are connected to what they want to share, because music is really about sharing. We do a lot of competitions and we do a lot of this and that, and sometimes we struggle to have work and it puts us in a competitive mindset. But in fact, I try to always say to my students something I learned from my teacher Rita Costanzi: you teach what you have to learn. I think that we just have to always be ourselves, and then we will connect with people, because I connect with a lot of artists, and they’re all different. They all have something to say. And I always fall in love with artists when I feel they are just truly themselves. So I think that’s the only mission for artists. For institutions, I think they need to trust their audience—people don’t need that much. I was going through an orchestra’s descriptions of their concerts with a friend, and [the orchestra] wanted the descriptions to be so educational, but [my friend] pointed out that he felt the descriptions created the opposite effect of what they wanted. [The orchestra] wanted people to feel attracted to it because people would understand things, but by explaining so much, people feel that they’re not going to a concert, they’re going to a lesson, and that is far from what they want to feel when they are in a concert hall. You just want to relax and feel emotions—whatever those emotions are. I think institutions just have to trust people and work on the access they give to what they do.

HC: You talked about your exposure to classical music when you were young. Was there a moment or an experience that sparked your interest in pursuing music as a career?

VM: I’ve been thinking about that a lot because it’s always been clear to me that I would be a musician. I remember when I was having lessons in school about choosing a career, I was very stubborn about playing music, even though they all say that it’s very hard and it’s difficult to earn money doing music and everything. But I was really fixed on being a musician. I do remember Caroline Lizotte playing her Techno Concerto with the orchestra in my hometown. I was sitting in the balcony, in the first row, not even really sitting on my chair, listening to her. I was super absorbed, and I had what I would call an epiphany—a moment in awe of how authentic she was. Of course, I am always very absorbed by all of her music, but seeing her with that instrument that I also played, being totally herself, playing the music she wanted in the way she wanted, with no regard to any convention, was just so cool. Her authenticity about being a harpist and an artist really touched me. This authenticity is something I always think about when I go to concerts and listen to musicians—it is something that really speaks to me. There is a pianist from Quebec but who lives in Boston—Marc-André Hamelin—who I am an absolute fan of. I just love that he appears to be so simple, he could be your brother-in-law or something. He just sits at the piano and starts to play with this pure intention and this experience of a life with this instrument. Listening to him is the same feeling as this sip of wine that’s just so perfect. I consider myself to be as much a music listener as a musician, and I think both nourish me. Being a musician nourishes the way I listen to concerts. But listening to concerts also nourishes what I do in my life, which is play music.

HC: You mentioned that Caroline Lizotte is your harp mom of sorts. And you also studied with Rita Costanzi in New York. Tell us a little bit about how those two experiences shaped you as a musician.

VM: I had four teachers over the years, and every teacher had a different influence on my evolution. I started with Marie-Josée Larprise here in Montreal, she was my first teacher. She was the one who made me love the harp. She was the one who helped me discover the harp. Hers was the first harp concert I went to. She also introduced me to the community around the harp. We had a big class, and we would have class concerts where we would all be stressed to play in front of each other, but then we would just share with each other. This is something I always try to do when I play concerts—connect with people, chat with people who come to a concert, and share a good meal with people afterwards. I think this mindset of sharing is very important, and she gave me that. I also studied with Manon LeComte. Caroline [Lizotte] was the teacher I had for the longest period of time, and she was also the most influential in the most profound aspects of my playing and my technique. She’s the one who formed me in any technical or interpretative aspect of my playing. But also, she was a very good teacher for being a teacher. All of my teachers inspire me every day when I teach, because they are people who give so much and who care a lot about their students. This has helped me a lot because being a teacher is about teaching the harp, but there is also a very personal aspect to it, and it helps inform what I do now in the conservatory. I form future professionals, and there is a big psychological influence I feel you have on your students, and those teachers were very aware of this. I could call them any time I was stressed, and we went through very important things in my life together. They were not calculating their time, and they were very generous. Rita [Constanzi] was the last teacher I had, and I think she was the right person to study with at this moment of my career, because I was starting to play a lot and feeling a lot of pressure about it. Also, I was very young at that time—I was in my early twenties—and I needed that person who would tell me, “Just be yourself, and people might love it or they might hate it, but they will remember you if you just are yourself and play with passion.” So those moments of going to New York and spending a few days with her were very, very fertile. Yes, it was about playing the harp, but it was also about being a musician. It inspires me every day, even now.

HC: Creative work takes a lot of energy and a lot of time. How do you find time to do everything?

VM: I ask myself this question all the time. I think I have a hyperactive aspect to my personality, although I consider myself as quite calm. In my family, we were always doing things. I am not a person who likes when things are static. I like being on the road. I like meeting new people, even though I like to have my little family bubble too. I’m very enthusiastic, too, which is sometimes a problem because I want to be involved in so many projects. At some point I have to talk to myself and say, okay, there are only 24 hours in a day and you’re supposed to sleep for a few of them. I think it’s the enthusiasm I have about this mission we’ve been talking about. When I feel that I can share things with people or that I can create opportunities for meeting with people, I feel so nourished, and that motivates me to work hard and to get things going. I am very interested in the entrepreneurial world and how entrepreneurs manage their time and don’t see things as being in boxes and go with their intuition. So I have worked this way and tried to be surrounded by people who are the same. Sometimes in my life I have worked with people who were not on the same page, and I totally respect that. I think that the problem, if it’s a problem with me, is that I perceive what I do not as work but as passion, really, and that sometimes I can be very intense with things because I’m just so passionate about them. But being a producer, having to employ people, I really learned a lot about myself and about others and my relationships with them. And I’m a very caring person. I have a very strong motherly instinct with people, so I try to listen to them and deal with their energy and not try to ask people to be at the same level of energy as me. And so I think I will be learning about myself and others all my life, but it’s going well now. I see it as a very interesting adventure.

HC: You have a John Cage quote that’s prominently displayed on your website that says, “I can’t understand why people are frightened of new ideas. I’m frightened of the old ones.” How do you think this mindset drives your creative pursuits?

VM: It’s a motto that is really significant in my life because I think that by being in the past, we block ourselves. I am very interested in history and everything that led to where we are today. But I feel that when I’m in the creative process, I have to think about now and the future, and I have to think out of the box. We were talking earlier about the classical music business where it’s very rare to make money on recordings, and you have two choices. You can resist that and be stubborn about it and think that people will magically start buying CDs. Or you can just accept that it’s not the same anymore. Now, of course, some things need to change, but you have to be creative and try to adapt in the way you face life and face the music business. So [the quote] is about this and about connecting to how people are today. When I look at myself, I’m not that old, I’m just 37, but I feel old sometimes. Sometimes I feel old and sometimes I feel young. With my students and my kids, I’m very interested in seeing how they absorb culture, how they perceive themselves in the world. I think it’s very important as we get older that we always stay connected with the people who are creating the future because there’s no point in looking back and trying to make things the way they have been in other contexts. I think it’s very Canadian or American to have this mindset that everything is possible and you can try things. It is how great things happened in music history—people trying new things and starting new trends. •

Have you heard?

If you haven’t been lucky enough to catch Valérie Milot in a live performance, her extensive library of recordings—both audio and video—provide ample opportunity to hear and see her perform.

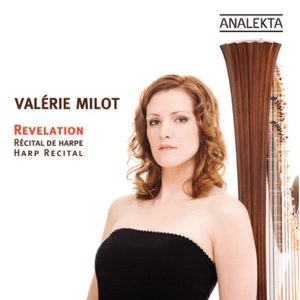

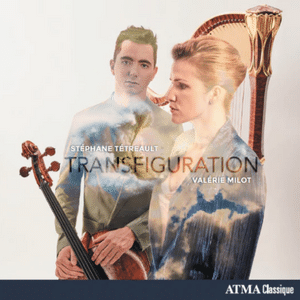

Audio

Milot released Revelation, her first of ten recordings, in 2009. “I think your first recording is always the most stressful repertoire-wise because your first recording is a sort of expression of who you are as a musician.” She notes that much has changed in the market in the last 15 years. Transfiguration, her latest album with cellist Stéphane Tétreault, reflects her current recording philosophy. “I see [recordings] like a derived product of my tours. Often when I record a CD, it’s because I will be touring this music on stage, and the CD is something that people can take home to have as a souvenir of the show.”

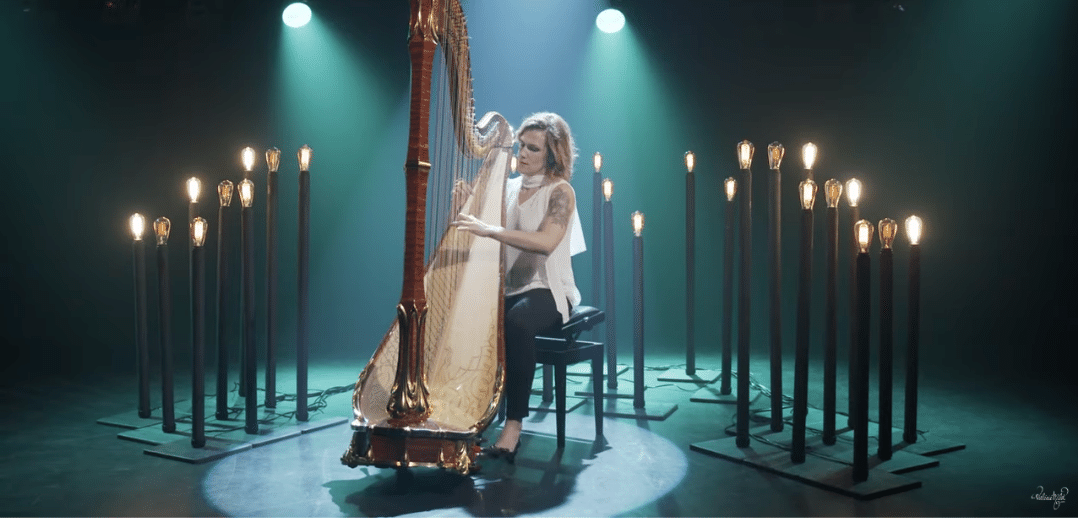

Video

Milot creates videos in collaboration with a professional videographer and audio engineer. She told us in the article “See and Be Seen” in the March/April 2015 issue of Harp Column, “To make a high quality performance video, I always work with a professional team. This way, I can fully concentrate on the performance and be sure that the result will be okay. Since you can never really delete something that you post online, I try to make sure that I’m satisfied with my playing before posting anything.”