Playing Bach’s music on the harp requires a slightly different approach than harpists use for music originally written for the instrument. To help guide you through Bach-specific skills, I’ve created this basic primer with explanations and examples. Learning these skills also enhances your playing of traditional harp repertoire, so you’ll get a lot of bang for your Bach. (Sorry, I couldn’t resist.) Throughout this primer, I will refer back to the six pieces featured in the “Bach for All” article on pg. 12 as examples where Bach employed some of these techniques.

A bird’s eye view of Bach

What’s new

New information about Bach’s music is always coming out. To stay up to date, visit www.bach-digital.de. (Search by the BWV number.)

Bach’s music is contrapuntal in nature. Think multiple melodies (lines) moving horizontally across the page rather than a vertical, chordal approach. Or, think how different the opening page of Faure’s Impromptu is (chord, chord, chord, chord, etc.) from the multiple melodies in most of Bach’s music. Both types of music are great; each just requires a different approach.

In Bach’s music, phrasing the individual lines, as well as how they interact with each other, is the most important part of playing it well. It is also a skill that will enhance all of your harp playing, even in chordal music.

During the late Baroque period, all musicians knew how to improvise, and adding their own ornaments or embellishments was expected. It was a way to show off a player’s technique and musicality. Bach, who lived during the late Baroque period, wrote very busy music that is full of dense, though beautiful, counterpoint. Because of this, there often isn’t much space for performers to add their own ornaments. (In fact, musicians during Bach’s day sometimes complained that he was spoiling their fun!) Instead, I would recommend that we honor the ornament symbols that he includes in his scores and look for “tasteful” places to add our own embellishments, especially at major cadences and during repeats.

Composers during the Baroque period did not always write in dynamics or articulation marks. Not only did this save them time, but they also knew that the musicians of their day had a shared body of knowledge and would know what to do. Today, it is important to learn about standard Baroque conventions and to honor them. I’ve listed some important ones below and have included some dynamics (in parentheses) in the edited editions. For articulation, I’ve included fingering suggestions. For example, connected patterns sound more legato than detached sections (staccato).

Tasteful choices

I have used the word “tasteful” a lot, but what do I mean by it, especially as it relates to our choices of tempos and ornaments? Learning about the style of music in any period takes time and quite a bit of patience. There are a lot of different opinions about how to play Bach’s music, which can feel overwhelming. Reading, listening, and engaging your own musicality are all important in determining what musical choices are appropriate for the music.

Take Bach’s dense counterpoint, add the harp’s active resonance, and it can equal a muddy mess. How do we fix this potential problem? Extra attention to our muffling! In my editions, I’ve included a number of places to muffle to help with clarity. I have included specifics later in the article about different types of muffling we can use in his music. These are also great skills to use with our standard harp repertoire.

The harp’s resonance also means that we need to be careful with tempos. I find better success playing Bach’s music on the harp when I take slightly slower tempos than a pianist or harpsichordist might choose. This allows all of the beautiful counterpoint to be more clearly heard. It also helps us with phrasing and clear articulation of the ornaments. And remember the importance of phrasing metrically in “bigger beats.” This way we avoid the dreaded “perpetual motion” monotony that can happen when there is little rhythmic shaping. For example, pieces in 4/4 time are often felt “in 2” and works in 3/4 time are often felt in 1. This doesn’t mean to go faster; it simply means phrasing pieces using slight metric accents (also called “agogic” accents) on stronger beats and shaping the phrases towards the bigger beats.

Repeats are another way to showcase your musicality. During the Baroque period, it was expected that the performer would make “tasteful” changes to the score as a way to be expressive. Feel free to experiment with dynamic contrasts in the repeat sections, as well as playing on different areas of the strings, such as a little lower (bdlc) or close to the soundboard (pdlt). Adding or changing ornaments is another fun way to add variety during the repeats.

Bach’s highly chromatic music will solidify your pedal technique. Make sure to practice your pedals with precision and consistency. Again, this will enhance your playing of standard harp repertoire as well.

Counterpoint

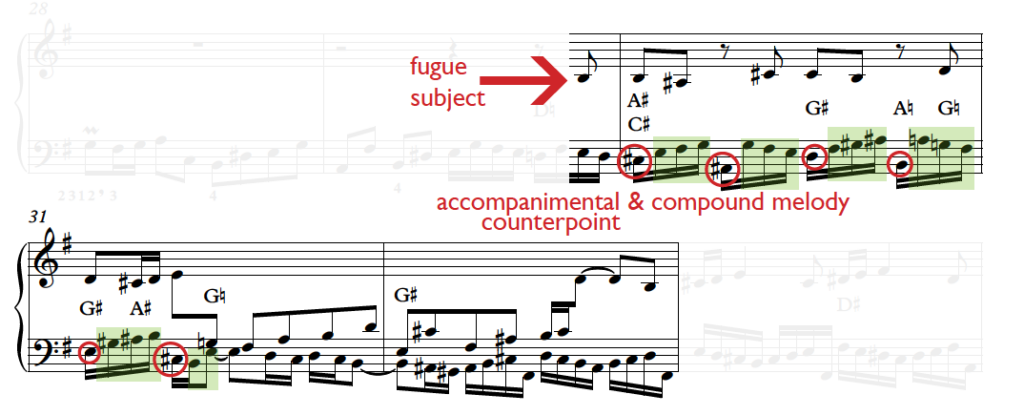

Let’s take a closer look at this short excerpt from Bach’s “Prelude in E Minor,” BWV 830. (See Ex. 1) It’s the fifth featured piece in the “Bach for All” article. We can see a statement of the fugue subject in the treble voice, accompanied by contrapuntal material in the bass voice. To articulate this type of contrapuntal writing on the harp, make sure to thoroughly learn each line separately (sing it in your head as you play and also when you’re away from the harp!) and to musically and rhythmically shape each line. Only then can you put them together and enjoy the interplay between the two.

We also have a bonus in the bass clef of this example: a compound melody in measure 30 through the first half of measure 31. This means that we have two melodies in one. To articulate this, bring out the bass notes (circled in red) a bit more than the countermelody (highlighted in green) in the upper notes on each beat. It is such a beautiful effect on the harp.

In a nutshell, with contrapuntal playing we are simultaneously phrasing independent melodies according to their different degrees of importance. In this example, the fugue subject should be brought out each time more than its accompaniment. And within the accompaniment we have our bonus compound melody with the bass notes being more prominent than the upper notes. It sounds like a lot—and it is—but with some patience and persistence, you will gradually get better at this. And the end results are incredibly satisfying for both you and your audience.

Pro Tip: Try listening to recordings of master performers of contrapuntal playing, such as the pianists Murray Perahia, András Schiff, and Rosalyn Tureck (my Bach teacher); violinist Hilary Hahn; and anything that the Netherlands Bach Society plays. Lots of inspiring performances out there!

Ornaments

Bach considered ornaments so essential to learn from an early age that he included his only example of an ornament table on the first page of his notebook for his son, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach. (See Ex. 2)

In our six “Bach for All” pieces, he included several basic ornament symbols. Let’s take a closer look at each:

Appoggiatura

In our first piece, BWV Anh. 113, we find several examples of appoggiaturas. Their purpose is to create dissonance by delaying the resolution to the principal, consonant note.

How to play an appoggiatura:

- Play the dissonant note (smaller notehead) on the beat.

- Plan to “lean into” (give a slight emphasis to) the dissonant note and then play less on the consonant resolution of the principal note (larger notehead).

- The appoggiatura takes one half of the value of the principal note.

- If the principal note is dotted, then the appoggiatura takes two-thirds of the value of the principal.

- Keep in mind that, traditionally, there was some flexibility in the exact rhythmic values of the appoggiaturas during the late Baroque. Follow these suggestions, and also use your good musical taste and adjust accordingly. The goal is to move our listeners’ emotions.

- In my editions, I’ve given rhythmic suggestions and fingerings for all appoggiaturas.

Fun fact: On Bach’s ornament table (numbers 9 and 10 in Ex. 4 below), you’ll notice that he notates appoggiaturas slightly differently than we do today. He used a hook instead of a slur and called them accents (in German, steigend for an upwards appoggiatura and fallend for a downwards one).

Short trill

Bach notates short trills in two ways, the traditional tr. symbol (which can also mean a longer trill) and a short, wavy line (See Ex. 5). We see an example of the tr. symbol in our first piece, BWV Anh. 113, and examples of the wavy line in our fifth and sixth pieces (BWV 830 and 998).

How to play a short trill:

- For most of our examples, plan to play four notes total, always starting on the note above the printed note (the upper neighbor, in the key) and start the ornament on the beat.

- I almost always use the fingering 2-3-1-2 to play short trills. This allows for speed and a relaxed hand. I will sometimes replace my thumb while playing the last note to muffle out the dissonance, a single-finger muffle. (This is not for beginners, but I do introduce it to my students fairly early on. It’s sonic magic to have a clear sounding trill with the single-finger muffle at the end.)

- Short trills are always within the tempo and the character of the piece and are never played fast like in the Romantic period. They are not grace notes, but are an embellishment of the line, not something extra. Make sure to play them lyrically and musically.

Mordents

Mordents are the only ornaments that do not start on the note above the printed note. In other words, they start on the printed note, go below it, and return to it. Simple, right? And so effective! Like a quick dash of chromaticism to spice things up. Bach indicates mordents in our fifth piece, BWV 830. (See Ex. 6)

How to play a mordent:

- Start on the printed note, play the note below it (in the key), and return to the printed note.

- Always start the mordent on the beat.

- I tend to use either 2-3-1 or 1-2-1 as fingerings for mordents.

- I almost always use a single-finger muffle to dampen the second to the last note, like with short trills. Replacing your finger on the middle, dissonant note results in beautiful clarity.

There are many more types of ornaments and a lot of subtlety that I go into in my editions and articles. I hope this introduction might inspire you to start experimenting with ornaments and perhaps add some during repeats as well!

Dynamics and Articulation Marks

Since dynamics and articulation marks are not frequently included in Bach’s music, it is important to honor them when they are there and look for similar places to use them.

For dynamics, contrast is more typical than long crescendos and decrescendos (which is more common in Romantic music). Yes, be expressive, but tastefully so, and remember to vary the dynamics during melodic and sectional repetitions. Imagine a sonic world in which subtlety and finesse were in fashion rather than extremes and melodrama.

For articulation marks, also look for any printed examples and apply them to similar places throughout the piece. Slurs are especially important as Bach frequently repeats and develops ideas that include them. Be consistent throughout. In my editions, I often include placed fingerings for legato passages and detached fingerings for shorter or staccato passages. Coming off (not connecting) after a slur is a good idea if time allows.

Muffling

I love how refined my muffling technique has become since I started playing Bach’s music. Not only can we use our traditional one- and two-handed muffles, but also single-finger, open left-hand, and registral muffling.

I use single-finger muffling to get nearby and distant notes out of different harmonies that can create muddiness. (And I always use them for ornaments.) This type of muffling can be done by simply replacing a finger to an adjacent string or by jumping to a note. It is typically notated using a diamond symbol, though I did not include any in our six Bach pieces. Don’t be surprised if this becomes a habit that you use with all of your music, especially with ornaments and stepwise passages. The clarity of line can be addictive!

There are two types of open left-hand muffles: the open thumb (+), where lower notes are muffled, and the open fourth finger, which dampens higher notes (See Ex. 7). Both get out a lot of sound and are important to use after long stepwise lines or changing harmonies. I have included places to use this technique in a number of our six pieces, but it can be left out if you’re not comfortable with it. This one will come with time, and again, you might find yourself automatically adding it to your other pieces as well.

Registral muffling means to muffle an indicated area of strings, usually less than an octave, with the left hand. (See. Ex. 8) While there are no suggested places in our six pieces for this technique, I have included it in many of my other Bach editions, and it is useful to know about.

Tempo and phrasing

A thoughtful approach towards tempo and phrasing is one of the most important parts of creating a successful interpretation of Bach’s music on the harp. Keep in mind:

We harpists often need to take Bach’s music a bit slower than other instrumentalists because of the resonance of our instrument. If we go too fast, the counterpoint can sound muddy and unclear.

If you’re playing a dance-inspired piece by Bach (menuet, sarabande, gigue, etc), keep in mind the rhythmic tendencies of these Baroque dances. Some examples include taking menuets “in one” and emphasizing or phrasing to beat two in sarabandes. While these pieces are not meant to be danced to, they were heavily influenced by the popular dances of the Baroque. Pro tip: Check out videos of Baroque dances to see what rhythmic qualities each one has.

In order to avoid rhythmic monotony, phrase in bigger beats (in 1 or in 2 depending on the time signature). Also look for places to “breathe.” How to shape the many sixteenth notes in his music will be one of the most important things you can do in preparing your interpretation.

Bach often starts his pieces with a rest. This is a huge clue! Since he’s starting the piece on a weak beat, plan to phrase to the next strong beat and to keep this phrasing consistent throughout.

One final tip: Try thinking of Bach’s music like a puzzle. If you have a question about interpretation, look for a solution in the score, and you will often find your answer. Don’t be afraid to experiment and try different ideas. If it flows and is clear to the listener, it’s probably “tasteful” and correct for the harp. Go with confidence and watch your technique and musicality grow as you play more of Bach’s brilliant music on the harp. •