Imagine being 9 years old and your father, Pablo Picasso, wants to teach you how to paint. Or your mother, Jane Austen, decides she’d like to teach you how to write. Or your father, Johann Sebastian Bach, announces he wants to teach you how to play the keyboard. What would it be like to study with a master of their craft while growing up under the same roof? How would they teach you, a novice? How would they guide you through the learning process? How intimidating and demanding would it be?

As luck would have it, we have some insight into what this might have been like, because it was exactly the scenario in which 9-year-old Wilhelm Friedemann Bach found himself in 1720. Wilhelm Friedemann was J.S. Bach’s oldest son, and the time had come for him to start learning the family business. Needing instructional materials, the elder Bach assembled a collection of his own pieces, graded according to difficulty and different techniques, while the family was living in Köthen, Germany. The Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Notebook (or in German, Clavier-Büchlein vor Wilhelm Friedemann Bach) is a fascinating collection and gives us a glimpse into what it might have been like to learn music from one of the world’s most famous musicians, J.S. Bach.

Where to find Bach

All of Bach’s music is in the public domain, so each of these original scores is available free on IMSLP.org.

Laura Sherman has also edited each of these pieces for harp, and the PDF downloads of her transcriptions with fingers, pedal changes, and other markings are available for purchase on harpcolumnmusic.com.

Bach wrote two additional notebooks for his second wife, Anna Magdalena Bach (in German, Notenbüchlein für Anna Magdalena Bach), in 1722 and 1725. They contain works written by Bach, as well as other composers, and include keyboard and vocal music. All three notebooks showcase Bach’s brilliance as a composer and teacher and are considered invaluable resources for aspiring pianists.

They are also beneficial for us harpists since much of Bach’s keyboard music transfers well to our instrument. The assorted levels and introduction of fundamental skills give us an early entry point into Bach’s music and allow us to gradually develop our musical abilities. No more envying our musician friends who have original Bach works in their repertoire and can start studying his music from an early age. (Talking to you, string players, flutists, pianists, and lute/guitar players!)

But why, you may be asking, should I learn Bach’s music on the harp? He never wrote for the instrument, and we already have plenty of original compositions to learn. If you are interested in the most concentrated, efficient, satisfying way to improve your technique and your musicality, then Bach is the composer for you. Every single piece teaches us something new and challenges us to grow. Learning to phrase his glorious contrapuntal melodies while navigating beautiful harmonies is unlike anything in traditional harp repertoire, and yet it also helps prepare us for our standard harp pieces. In a nutshell, and in my opinion, it trains our fingers, ears, mind, and soul.

To demonstrate just how accessible Bach’s music is and how much it can teach harpists of all abilities, I’ve picked six keyboard pieces ranging in difficulty from beginner to advanced. They each provide opportunities to learn valuable technical and musical skills. Three come from the Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Notebook; two from the 1725 Anna Magdalena Bach Notebook; and the last, an advanced work that does not come from any of the notebooks, the “Fugue” from the Prelude, Fugue and Allegro, BWV 998, which was reportedly written for the lute (or more likely, the lute-harpsichord). I included this last one because Bach was a master of fugal writing and, in my opinion, being able to play a fugue on the harp is one of life’s greatest musical joys.

No matter where you are in your musical journey, you will find an entry point into Bach’s music in one of these six pieces. All are playable on the pedal harp, and the second and third pieces I’ll highlight below also work well on the lever harp. Since we aren’t lucky enough to have Bach guiding us through this music like young Wilhelm Friedemann, I’ve also included suggestions about how to get the most out of each piece. So, tune your harps, and let’s get started learning more of Bach’s brilliant music!

1. Menuet in F Major, BWV Anh. 113

beginner level, pedal harp

Overview: This work is good for beginners once they can play different lines in each hand. This piece develops hand independence, introduces two basic ornaments, and teaches an awareness of contrapuntal playing. If needed, the ornaments can be left out until the student’s technique advances. The left-hand open thumb can be replaced by a traditional closed-thumb as well.

Background: While we are not sure if J.S. Bach actually wrote this piece, he included it in his 1725 notebook for his second wife, Anna Magdalena Bach.

Fun fact: The “Anh.” after the BWV number for this piece is an abbreviation for “Annex” (in German, Anhang) and is a list of lost, doubtful, and spurious compositions by, or once attributed to, J.S. Bach.

Why is this piece brilliant?

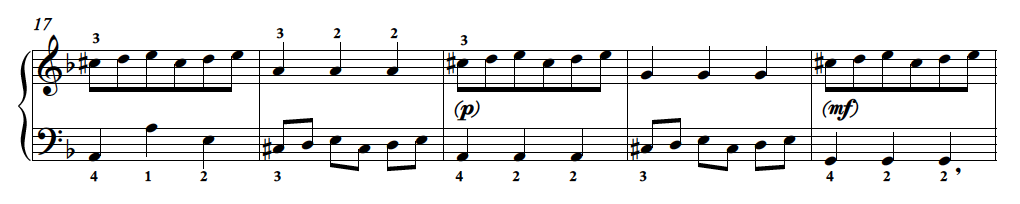

- The “division of labor” between the hands in this piece is excellent for a beginner harpist, with each hand having plenty to do. The exchange of melodic roles between the hands, especially in measures 17–21, is a great introduction to Bach’s contrapuntal writing. (See Ex. 1)

- Ornamentation! Two basic ornaments (the appoggiatura and the short trill) are introduced in this piece and provide interesting melodic color. See the “Bach to the Basics” primer on pg. 19 for details about how to play these.

- Rhythmic variety, especially at the start, also makes this piece perfect for a beginning harpist. (See Ex. 2)

- Minuets (or menuets, as Bach spelled them) are always fun to play!

Keep in Mind:

- Best to do a lot of hands-separate practicing first. This will make playing hands together a smoother experience.

- Connect as much as possible to gain melodic freedom and fluidity. The suggested fingerings should work for most. Make sure to use directional placing.

- If you are not comfortable playing the left-hand open thumb (+), use the traditional closed thumb position. This can be added later as the student’s technique progresses. (The open thumb helps to muffle the previous harmonies and provides clarity.)

- If you are not comfortable playing the ornaments, leave them out at first.

- Dynamics have been added when there is a direct repetition, as is traditional in German late Baroque music. Look for creative changes when taking the repeats, using dynamics, changes in register (closer to the soundboard, bdlc, or pdlt), or “tasteful” adding or changing of ornaments.

- Make sure to bring out the shifting melodic lines (the counterpoint).

- Aim for a warm, even, and lyrical sound.

- Because this is a minuet, the tempo should not be too fast. Phrasing the piece “in one” is characteristic of a minuet (which is like a waltz).

If you like this piece, you might also enjoy…Bach’s “Menuets,” BWV Anh. 114, 115, or 116 (ed. Maria Luisa Rayan).

2. Praeambulum 1 (Prelude 1) in C Major, BWV 924

advanced beginner level, lever and pedal harp

Overview: This piece is good for an advanced beginner and can be played on either the lever or pedal harp. It does require some pedal/lever ability, especially towards the end, and develops independence of hands. It also builds familiarity with common hand-shapes and left-hand fingering patterns found in Baroque music. If needed, the left-hand open thumb can be replaced by a traditional closed-thumb. The original ornaments have been left out here, but are included in the complete edited version (available on harpcolumnmusic.com).

Background:This is the second piece in the Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Notebook and works beautifully on the harp because of the flowing arpeggios.

Fun facts: Praeambulum is Latin for “preamble” or “prelude” and while the work’s title is originally listed in Latin, it is also correct to list it as a “prelude.”

This Prelude was also included in a 19th-century collection of works by J.S. Bach and others titled Twelve Little Preludes and published together in the Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe (BGA). It is listed as BWV 924–930, 939–942 and 999.

Why is this piece brilliant?

- Arpeggios! One of the things that the harp does best!

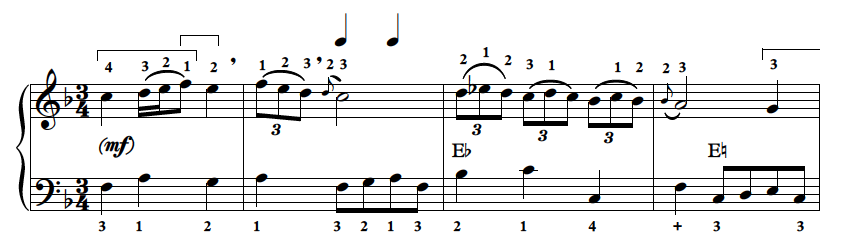

- Conventional left-hand patterns: you will use these valuable patterns for the rest of your Bach-playing life. Plus, they are a lot of fun once you get the hang of them. (See Ex. 3)

- Introduction of more chromaticism: A great way to develop your pedal or lever technique! (See Ex. 4)

Keep in Mind:

- The suggested fingerings should work for most. Make sure to connect as much as possible and to place precisely to facilitate fluid, clean playing, and eventual speed.

- For the right hand, seeing and feeling the shapes of the patterns is important. Think harmonically to help with learning and memorization.

- Also important is to completely close the hand after each pattern to release tension and produce a warm sound.

- The patterns in the left hand are very common in Baroque music and will serve you well going forward. Added bonus: they are fun to play!

- If you are not comfortable playing the left-hand open thumb (+), use the traditional closed thumb position. The open thumb can be added later as your technique progresses. (The open thumb helps to muffle the previous harmonies and provides clarity.)

- For lever harp, tune the instrument to E-flat major and use all right-hand fingerings when the left hand is needed to change the levers.

- For pedal harp, make sure to change the pedals exactly at the indicated place, feeling the rhythm of the changes for consistency. (This is a great lifetime habit too.)

- Careful to make mm. 11–17 as smooth and lyrical as possible. Even though you are dividing the line between two hands, it should sound like one hand. For the lever harp, continue to use the right hand when you need to use the left to change levers.

- The tempo should feel like it is in two, while staying consistent throughout and not too fast!

- Look for places to phrase and breathe, especially from measure 9 to the end. A slight “tasteful” slowing down in the last two measures is fine, but do so for musical reasons, not because the pedals are more challenging.

- In the original, all the left-hand G octaves in measures 11–17 are tied. But since the harp does not resonate as long as an organ, rearticulate the G octaves in the left hand in these measures (as indicated in this edition).

If you like this piece, you might also enjoy…Bach’s “Prelude in C Major,” BWV 846 from the Well-Tempered Clavier (ed. Renié, Sherman, and many others).

3. Praeambulum (Prelude) in F Major, BWV 927

advanced beginner level, lever and pedal harp

Overview: This piece is good for an advanced beginner and requires no pedal or lever changes, nor any knowledge about ornaments. It develops independence of hands, wrist release after single dyad articulations, and cross-under patterns in the left hand.

Background: This is the eighth piece in the Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Notebook and works beautifully on the harp because of a combination of arpeggio and scale patterns.

Fun facts: Same as the fun facts in BWV 924!

Why is this piece brilliant?

- A wonderful variety of techniques: arpeggios, scales, connected and detached playing.

- Without ornaments or pedal changes, you are free to focus exclusively on the techniques above.

- A fun dialogue between the hands, trading melodic ideas back and forth. (See Ex. 5)

Keep in Mind:

- Remember to use directional placing throughout for sonic clarity and healthy hands.

- The comma sign (,) means to come off after each dyad.

- In the detached dyad figures (like the left hand at the beginning), think about hand shapes and stay close to the strings as you come off each time. A little wrist-back action can help release tension and create a subtle bouncy action (which promotes relaxation).

- Stay relaxed when playing the arpeggiated figures, like in the right hand at the beginning. Adding a little (one-way) oscillation with the wrist can help release any potential tension.

- In mm. 5–8, go for a clean legato and a long line in the left hand.

- There are two options for fingering in measure 13.

- The circled 4 in measure 14 means to use an open hand to play the low E with the left-hand fourth finger. This helps to muffle some sound. It’s followed by a traditional muffle to completely clear out more sound before the fun ending.

- Feel free to arpeggiate the last chord tastefully or perhaps add a little ornament if you are inspired!

If you like this piece, you might also enjoy…Bach’s “Prelude in F Minor,” BWV 881 or his “Prelude in A-flat Major,” BWV 862 from the Well-Tempered Clavier (ed. Sherman).

4. Praeambulum 8 (Prelude 8) in B-flat Major, BWV 785

intermediate level, pedal harp

Overview: This is a good piece for intermediate students and requires few pedal changes. It develops clean, fast playing as well as introduces two-part counterpoint.

Background: This is the 39th piece in the Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Notebook and works beautifully on the harp because of the scale and arpeggio patterns. The two-part counterpoint is not too dense, providing a great introduction to this exciting type of playing.

Fun fact: In 1723, J.S. Bach also included this work in another collection of teaching pieces for his students, titled Inventions and Sinfonias, BWV 772–801, and also known as the Two-Part and Three-Part Inventions (contrapuntal works in two or three voices). This work is a two-part invention and is number 14 in that collection.

Why is this piece brilliant?

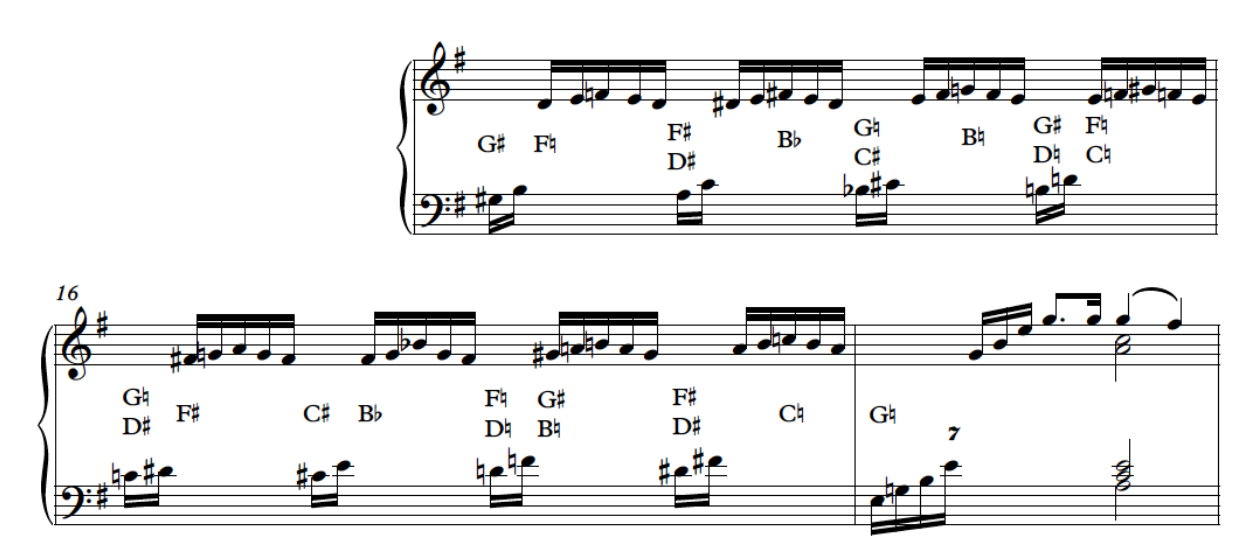

- Fast notes! This piece helps to develop a clean, fast technique without a lot of pedals and no ornaments to worry about. (See Ex. 6)

- Tension-free technique! There is no way to play this piece when tense. Relax and enjoy the playfulness of it. And make sure to completely release each time you come off of the strings.

- Helps to develop precise rhythm and articulation of longer phrases.

- The dialogue back and forth between the hands teaches the student about contrapuntal playing.

- True two-part counterpoint! The end of measure 16 through the end introduces true two-part counterpoint and is a thrill to play. (See Ex. 7)

Keep in Mind:

- A lot of hands-separate playing will help the hands-together experience go more smoothly.

- Aim for an efficient, precise, and relaxed technique, and make sure to completely relax the hands every time you come off the strings.

- The end of measure 16 through the end will take a lot of extra practice. Don’t give up! It is totally worth it to learn this thoroughly, and it is so satisfying to play.

- In the forward to J.S. Bach’s collection of two- and three-part inventions, he wrote the following to his students: “Learn to play two voices clearly…but most of all to achieve a cantabile (singing) style of playing.” Inspiration from the composer himself!

If you like this piece, you might also enjoy…Bach’s “Prelude in B-flat Major,” BWV 866 from the Well-Tempered Clavier (ed. Renié, Sherman) or his “Prelude” from the Keyboard Partita No. 1 in Bb Major, BWV 825.

5. Prelude in E Minor, BWV 830

advanced level, pedal harp

Overview: This piece is good for advanced students. The chromatic passages solidify pedal technique, and the improvisatory character develops phrasing skills and musicality. Two basic ornaments are included. See the primer for details about how to play them. (Fingerings for the ornaments are included in the edition.)

Background: This piece is from the 1725 Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach. J.S. Bach also included it as the opening movement of his Keyboard Partita No. 6 in E Minor, BWV 830, where it is labeled as a “Toccata” instead of a “Prelude.”

Fun Fact: “Toccata” comes from the Italian word, toccare, which means “to touch.” Bach often used toccatas to warm up his fingers on keyboard instruments (to “touch” the keys) and to test out organs. Toccatas are improvisational or more free in form and feeling and can be more rhythmically flexible than other movements. Thankfully, this fact also gives us more time to change the pedals during the chromatic sections!

Why is this piece brilliant?

- This is a monumental piece in its depth of structure, musicality, and emotion.

- Improvisatory passages, contrapuntal writing, diatonic and chromatic passages—this piece has it all and is a brilliant study in development and diversity. (See Ex. 8)

- The chromaticism is revolutionary and can be played on the harp because it is a prelude/toccata which allows for “tasteful” rhythmic freedom. And it is such a thrill to play! (See Ex. 9)

- Gorgeous compound melodies!

- Three-voice fugue! (See Ex. 10)

Keep in Mind:

- I’ve included fewer fingerings here because there are often several options available. Leaving more “white space” on the page was a deliberate choice to give you more flexibility to make this piece your own.

- This piece is in a three-part form: 1). Free/improvisatory and metric parts. 2). A three-voice fugue. 3). More free writing without the metric parts. (Buxtehude called this type of free writing “stylus phantasticus.”)

- The free/improvisatory passages can be more rhythmically flexible than the metric and contrapuntal ones. This will help with the extensive chromaticism and pedal changes. (But remember to be “tasteful” in your rhythmic flexibility.)

- Relaxed hands and full closure will help with endurance.

- In general, this piece should be felt in two, especially during the metrical contrapuntal passages.

- Playing contrapuntal music involves phrasing all melodies (lines) at the same time. It is an art form that can take time to develop. Singing the separate lines away from the harp can help facilitate this skill. Also, playing one line and singing the other. One has to hear it first, then one can play it. And there is nothing like the satisfaction of accomplishing this skill.

- Arpeggiate the chords as appropriate. Longer note values get longer arpeggiations while shorter note values get shorter arpeggiations.

- Two ornaments are included here—the mordent and the short trill. Start on the printed note for the mordent and start on the note above for the short trill. Fingerings are included for guidance, and more information is included in the primer. (See “Bach to the Basics” on pg. 19.)

- For the compound melody starting in measure 9 (and similar types of writing throughout), make sure to bring out both lines where appropriate.

- For the three-voice fugue, make sure to always bring out the fugue subject while shaping the other lines appropriately. Fugues (and ornaments) tend to take more work to learn than other types of Bach’s writing.

If you like this piece, you might also enjoy…Bach’s “Chaconne” from the Violin Partita No. 2, BWV 1004 (ed. Esposti, Owens, Kanga, and Lenaerts).

6. Fugue in E-flat Major from the Prelude, Fugue and Allegro in E-flat Major, BWV 998

advanced level, pedal harp

Overview: This piece is good for advanced students. While it has been edited to make it idiomatic for the harp, nothing has been left out or changed. As a rare instance of a three-voice da capo fugue by Bach (he only wrote three of these), it gives the harpist a genuine fugue experience. The stepwise nature of the fugue subject and the close intervallic content of the non-fugal writing work well on the harp. And while there is some chromaticism, it is perfectly manageable on the pedal harp.

Background: This fugue is the central movement of Bach’s Prelude, Fugue and Allegro in E-flat Major, BWV 998, which was composed between 1740–1745 when he lived in Leipzig. While it is typically included with Bach’s other works for the lute (BWV 995, 996, 997 and 1006a), it might have been written for the lute-harpsichord (Lautenwerk, in German) instead.

Fun fact: The Lautenwerk was a special type of keyboard instrument that was like a harpsichord but had gut strings to simulate the sound of a lute. Bach was known to have helped design a lute-harpsichord, and the writing is more idiomatic on a keyboard than a lute from that time. That’s what makes it so great for the harp too!

Why is this piece brilliant?

- A three-voice fugue that works well on the harp, and it’s a special da capo fugue, which means that the opening returns and is replayed in its entirety except for the first two measures. This is called an “elided return.” (See Ex. 11)

- The range of this piece works beautifully on the harp, with the fugue subject entering in the middle, low, and lower registers. Plus, it’s in a flat key, which resonates nicely on the harp.

- Learning to bring out and phrase the entrances of the fugue subject (as well as other contrapuntal writing) will absolutely enhance your playing of traditional harp repertoire. Playing contrapuntal music well is one of the most meaningful musical skills you can develop, and, in my opinion, also one of the most satisfying. (See Ex. 12)

- Because of the active contrapuntal writing, there are no ornaments in the original. (I added several optional ones at the ends of both A sections, however.) This allows space for cleaner contrapuntal playing on the harp.

Keep in Mind:

- This piece starts with a rest. This means that the fugue subject starts on a weak beat and should always be phrased to the next strong beat (downbeat). Even the middle section is based on an off-beat pattern, so continue this phrasing of weak-strong throughout.

- Always bring out the fugue subject, whether it appears in its entirety or in fragments.

- The piece is in a three-part form: A-fugue, B-development, A-elided return of the fugue. Make sure to keep a steady tempo throughout so that the return of the fugue is at the same speed as the opening.

- Feeling this piece in two is best and encourages longer phrasing.

- The tempo should not be too fast! My top tempo is 80 to the quarter note. Because the harp is such a resonant instrument, we need to take our tempos slightly slower than pianists or harpsichordists. Otherwise, the texture sounds muddy.

- I’ve added suggested places to muffle to help keep the counterpoint clear. A circled 4 means to play with an open left hand to allow for muffling. A “+” means to play an open left-hand thumb to help with muffling.

- Tasteful dynamics can be added. I’ve a suggested dynamic markings and put parentheses around them to indicate that they are not in the original.

- Bach didn’t often include slurs in his music. We are fortunate to have so many in this piece. Make sure to phrase these, thinking “strong, weak.” This phrasing was especially important in the Baroque period. When bringing out the dissonance resolving into consonance was thought to move listeners. This was one of the main goals of Baroque playing, to elicit emotional responses in every way possible.

If you like this piece, you might also enjoy…Bach’s “Fugue” from the Lute Suite in C Minor, BWV 997 (ed. Sherman).

I hope you have found a Bach piece or two that suits your current needs. Maybe you’ll even be inspired to try all of them over time. If you’re looking for more Bach to play, there is no shortage of options listed to the right. Thanks to the excellent work of many harpists around the world, we have an ever-growing assortment of Bach for the harp. May you be inspired to check out these great resources as well! •

Bring on More Bach

There is no shortage of Bach editions to try out on harp.

Merynda Adams, lever/pedal; int.; assorted works

Rhett Barnwell, lever/pedal; adv. beginner, int., and adv.; assorted works

Sylvain Blassel, pedal; advanced; Goldberg Variations

Pearl Chertok, lever; beg.–int.; Junior Bach assorted pieces (possibly out of print)

Stephanie Curcio, lever and pedal; int., assorted works

Victoria Drake, pedal; adv.; Complete Cello Suites

Emanuela Degli Esposti, pedal; adv.; “Chaconne” from the Violin Partita No. 2, BWV 1004

Catrin Finch, pedal; adv.; Italian Concerto, BWV 971

Marcel Grandjany, pedal; int.–adv.; Bach-Grandjany Etudes (arrangements, not transcriptions)

Skaila Kanga, pedal; adv.; “Chaconne” from the Violin Partita No. 2, BWV 1004

Angela Klöhn, pedal; int.–adv.; assorted works

Melvin Lauf Jr., pedal; int.; “Largo” from the Keyboard Concerto No. 7 in F Major, BWV 978

Anneleen Lenaerts, pedal; adv.; “Chaconne” from the Violin Partita No. 2, BWV 1004

Marcela Mendez, pedal; adv.; Keyboard Concerto No. 5 in F Minor, BWV 1056

Anne-Marie O’Farrell, lever; adv.; Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue, BWV 903 and assorted works

Dewey Owens, pedal; adv.; “Chaconne” from Violin Partita No. 2, BWV 1004

Isabelle Perrin, pedal; adv.; Lute Suite, BWV 996

Parker Ramsay, pedal; adv.; assorted works

Maria Luisa Rayan, lever/pedal; int.–advanced; assorted works

Henriette Renié, pedal, int.–adv., assorted works

Ailie Robertson, lever/pedal; adv.; “Allemande” from Lute Suite, BWV 995

Floraleda Sacchi, pedal; int.–adv.; assorted works

Laura Sherman, pedal; adv.; complete Lute Suites and “Preludes” and “Fugues” from the Well-Tempered Clavier

Diana Steiner, lever/pedal, int.; assorted works

Katrina Szederkényi, pedal; adv.; Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue, BWV 903

Katherine Thomas, pedal; adv.; Complete 48 Prelude and Fugues

Amy Turk, pedal; adv.; Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, BWV 565