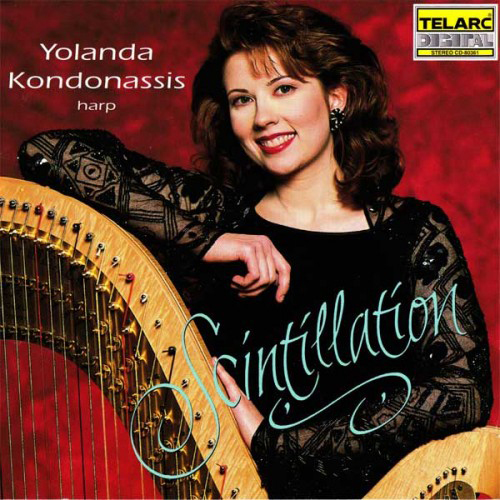

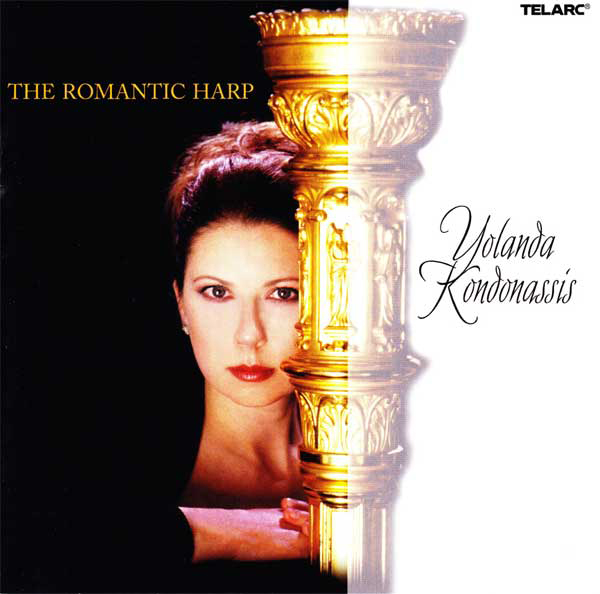

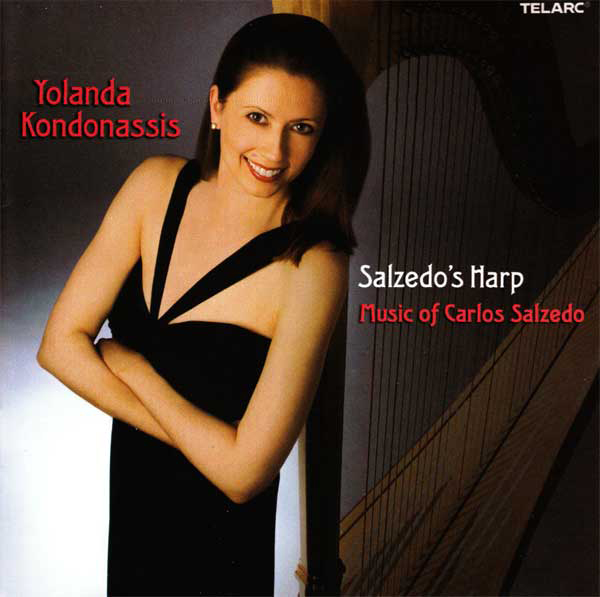

We interviewed Yolanda Kondonassis in 1993 for the cover of the second issue of Harp Column just as she was releasing her album Scintillation. It was the first commercial album for Kondonassis on the Telarc label, and the last time she let the label’s stylist do her hair for an album cover—back in the days when record labels were flush with cash to pay for hair and makeup and stylists. Kondonassis has gone on to make 22 albums in the last 26 years—prolific by any standard, and particularly impressive when you consider the wholesale changes in the recording industry during the same time period.

20/20

Recording then and now

A lot has changed in the last 20 years. From publishing to performing, the harp world looks markedly different than it did two decades ago. As we approach 2020, we’re checking back in with artists we featured on our cover prior to 2000 to find out how their corner of the harp world has changed—and stayed the same— since we first talked to them 20- plus years ago. You can read our first interview with Yolanda Kondonassis in the Sept./Oct. 1993 issue of Harp Column.

Looking back, Kondonassis says that summer of ’93 was really the point at which her career took off. The New York management company ICM signed her, Telarc released her first commercial CD, and she performed the opening concert for the American Harp Society National Conference.

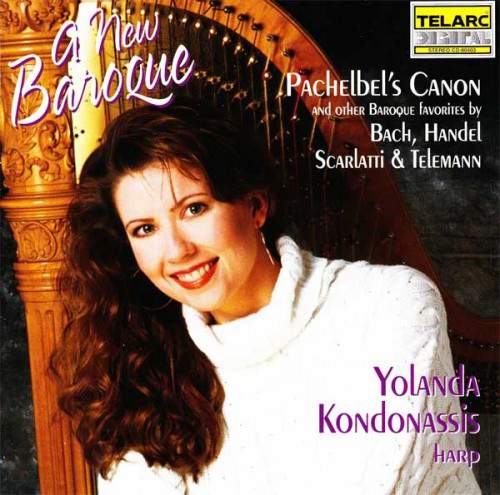

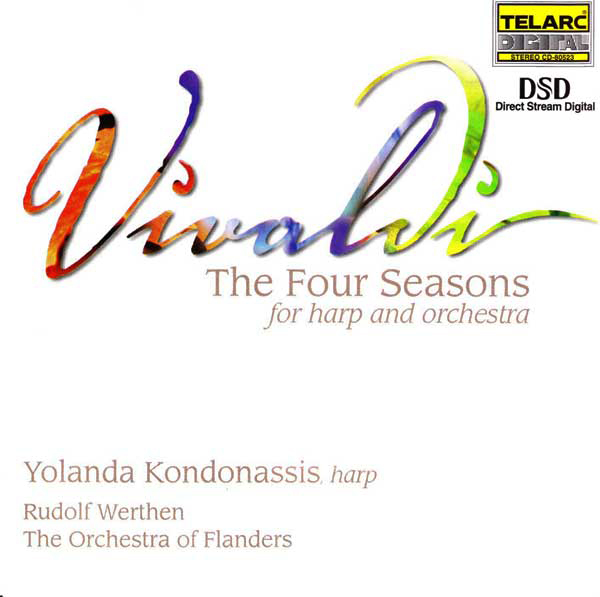

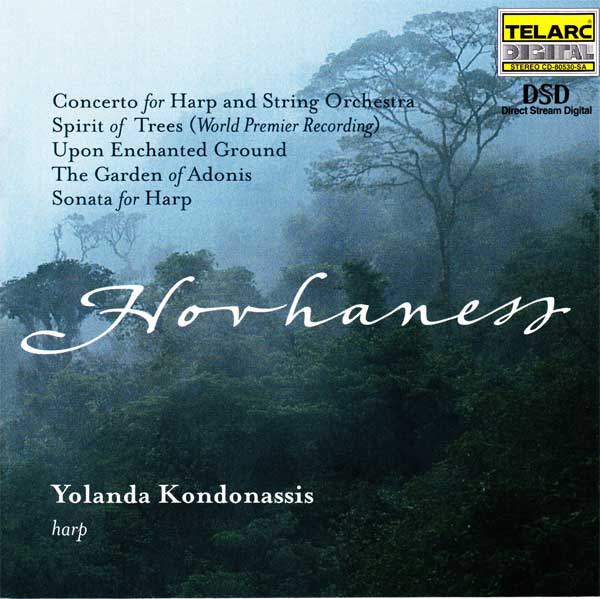

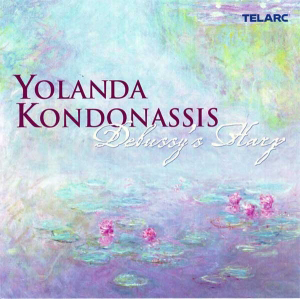

Kondonassis counts herself lucky to have made close to 15 albums on the Telarc label—long considered one of the premiere audiophile labels. “That was an education in and of itself. It was never enough for them to just lay down the tracks. What an incredible privilege to be able to record that way.” Kondonassis describes her approach to recording as “somewhat scientific,” which she says was inspired by her 20 years working with Telarc. “To this day, I approach a recording the exact same way, which is to research all the music, get my hands on any existing recording of the music so that I can stand back and see what’s good and try to learn from the pitfalls that I would hear—whether it was a lot of brightness in the top or a lot of extraneous surface noise, or whatever it was that may have been problematic on existing recordings. I would try to troubleshoot that before I ever got to the sessions.”

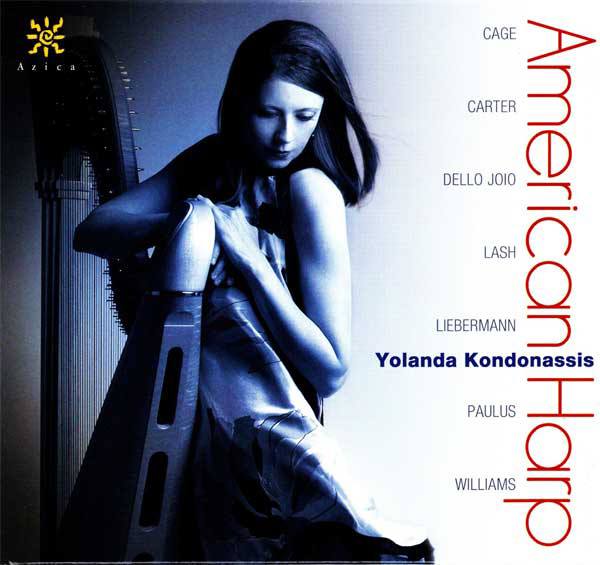

Telarc was bought by Concord Music Group in 2009, and more or less got out of the classical recording business. Today Kondonassis records on the Azica label, which she says follows a similar detailed approach to the process.

One thing that strikes you after a conversation with Yolanda Kondonassis is that nothing she does is by accident. She is intentional about every single thing she does and every single note she plays. Oh, and she works her tail off. No excuses. She is quick to admit she is a detail-oriented person—always has been. Back in 1993, she was known for her clean sound, crystal clear definition, and rock solid technique—her reputation remains the same today.

“I’m still sort of a clarity freak. But there are two sides to that equation. There is the technical side and there is the musical and artistic end of things. I would say that in those 26 years I’ve given enormous thought to the musical end of that equation. Full-on, all-in commitment musically to every single note you play is a priority. There should never be a casual note. There should never be an incidental phrase. Everything should have thought, which isn’t to say that you’ll always play everything the same way. Live music is like performance art—you’re creating something, you’re sculpting something in front of an audience. Everything is relative to everything else—what you’ve played before, how much energy you’ve got going on a particular night—there’s no set interpretation, but there’s a parameter of what you do and how you tend to approach and feel something.”

Full-on, all-in commitment musically to every single note you play is a priority. There should never be a casual note. There should never be an incidental phrase.

Musicians tend to get pigeon-holed into one camp or another—technical or musical. It’s the old musical dilemma: do you want to be technically perfect or musically transcendent?

“This has always annoyed me. I don’t believe it’s a choice. I believe you owe it to an audience for your chops to be in great shape. You need to deliver the notes accurately and with as much clarity as you can, but that does not preclude transcendent musicality. It has to be both. If you look at the great artists through time, it’s sure not a choice between the two with them,” she points out. “It’s not like you can slop through something incredibly musically and the result will be something sublime. That’s why playing music can be difficult and why it’s a talent. No compromises. It’s got to be as great as it can be on as many fronts as possible. Technique without artistry is nothing, but high artistry without technique to support it is far less than it could be. It cuts both ways.”

From CDs and record stores to digital music to streaming services, the recording industry looks nothing like it did 25 years ago. The biggest change Kondonassis says she has seen in recording over the course of her career is the removal of big labels as the gatekeepers of what recordings get made. You don’t need a record label to make an album anymore. All you need is a computer and an internet connection. It used to be difficult to find recordings of harp repertoire—your search might take you to dusty stacks at Tower Records. Today, finding a recording is as simple as a Google search. The difficulty lies in discerning the quality recordings from the lot.

But wait, that’s not all

In addition to recording, performing, and teaching, Yolanda Kondonassis has three collections, several arrangements, and one children’s book about the environment to her name.

- On Playing the Harp

- The Yolanda Kondonassis Collection

- The Yolanda Kondonassis Christmas Collection

- Gershwin’s Prelude No. 2

- Ravel’s Pavane pour une infante défunte

- Debussy’s Bruyéres

- Our House is Round

“When I made Scintillation, it was a big deal to make a commercial recording that was available around the world. It was a very different industry. There are so many more access points for audio products in every category, that it’s become hard to keep track of where the quality is. While there is some really fabulous stuff that gets thrown up on the internet, there is also some less-than-fabulous stuff,” she says. “I believe in the art of recording, and I feel really strongly that it should remain an art and not just something that you throw up randomly. There is a lot more to sort through today to find what is a polished recording versus what is a work in progress.”

Wading through everything that’s out there can be particularly difficult for young musicians eager to hear new recordings but inexperienced in identifying the best benchmark to shoot for.

“I know some teachers say, ‘Don’t listen to recordings; make your own interpretations.’ But I really believe you need to know what’s been done. Especially with the harp, you will find as many radically different interpretations of music as you will find recordings and harpists and performances. I think it’s a good source of inspiration for students to listen to really great recordings.” Kondonassis says her rule for students is to listen to many recordings, not just one recording, since there is a risk of getting married to what one person did on one recording. “Listen to a bunch, decide what you like, what you don’t like, be inspired, be a critical listener.” Kondonassis points out that it’s important to know who you are listening to in order to understand what the source of your influence is. She tells the story of a student who told her she had found this great recording on YouTube of a piece she was working on. Kondonassis asked her who made the recording. The student replied that she wasn’t sure, but she thought it was some other student’s junior recital. “Not that you cannot learn from someone’s junior recital, you can learn a lot. But first of all, that can’t be the only thing you listen to. Second of all, just like in life, you have got to be really mindful of your influences. Someone who is still in the baking stage in their junior recital might not provide the best source of polished, professional recordings.”

Kondonassis points out that a lot of the best recordings are on vinyl. “You’ve got to go to a real library and sit there with headphones and listen to Zabaleta and Lily Laskine and Marielle Nordmann and Marisa Robles and all those people who were pioneers.”

“Maybe this is an unpopular view, but I really believe in quality control. If you throw something up there that was a so-so recital performance, it might have been good, but it might not be anything close to what it could be and will be. Do you really want that in-progress performance out there for all eternity?”

This fall marks the start of Kondonassis’ 23rd year of teaching. She heads the harp department at her alma mater, the Cleveland Institute of Music, as well as the Oberlin Conservatory. “I’ve become a much better player since I started teaching, no doubt about it.” She thinks teaching is something everyone should experience. “It’s sort of the parenting equivalent of being an artist—you don’t quite understand everything until you try to share it.” Kondonassis points out, “You can’t take it with you, so if you’re not sharing it, it seems like such a waste of everything you’ve figured out.”

Kondonassis started teaching shortly after her career caught momentum, and she admits it was a lot to juggle at first. With age and experience, Kondonassis says her teaching is more “full service” than it was in the beginning. “As you get to an age where you are old enough to be the mother of your incoming freshmen, your teaching changes a little bit,” she reflects. “I’m not sure I got all up in everybody’s business nearly as much in the beginning of my teaching career as I do now. To be able to fully express yourself artistically on any instrument is a whole body, mind, psyche endeavor, and while I wouldn’t presume to analyze people, I really need to know what’s going on with them and why there might be a block. Do they have an unproductive boyfriend? Are they staying up all night? Are they eating nothing but sugar? So I get into things beyond the technical and the musical in a way I didn’t at the beginning.” Kondonassis adds, “I just really care about everybody a lot, and I want everything to work out for them. It’s a tough world, and it’s a competitive business Whatever edge I can help them have is really important.”

Kondonassis knows the power of having someone believe in you, support you, and tell you that everything is going to be okay. She says she’s been fortunate to have people in her corner at every turn. You can’t do it alone. Kondonassis also emphasizes the important of recognizing opportunities when they arise.

“I tell my students this all the time. In any field, you have to recognize your mistakes fast enough to fix them before they become big mistakes, and you have to recognize opportunities. Those are talents; they go beyond skills. I can’t tell you how many times a student has come to me and said, ‘I got this call [for a gig], but it sounds like a hassle, and I’m not sure it’s worth it.’ I’ll say, ‘Wait a minute. Do you know how many contacts that person has? And if you really bring it, do you know how much that could lead to?’ If anything, I think what has kept me recording and kept me in that creative zone is opportunity recognition. I see a good opportunity to make some good art, and I’m not thinking about all of the practical reasons it might be a hassle. I just get excited, and I plow forward. Sometimes that’s just what you need to do. There will always be 50 reasons why something is not practical or might be a hassle. But I’ll say yes and figure it out later.”

Back in 1993, Kondonassis said her desire to create something lasting beyond the fleeting moment of live performance was the motivation for recording her first album. “I still very much believe that whenever you are an artist, whether you are a visual artist or a dancer or a musician or a poet—you do want to feel like there is something tangible.”

When you put out nearly a record a year for a quarter century, some will see you as exclusively a recording artist. However, Kondonassis, who gives up to 60 concerts a year, says live performance and recording go hand in hand.

“Sometimes I find it a little bit amusing when I’m referred to as a recording artist, which I am, but you can’t really be a recording artist unless you are a live performing artist also,” she says. “Music can’t become a part of you unless you have performed it and had that live interaction with an audience. I don’t feel like I record to the exclusion of live performance, and when I finish a set of recording sessions, I cannot wait to get back on the road to live performance. It’s a completely different animal, and it doesn’t have the tedium of recording. In live performance you can let loose a little bit, you can take risks, whereas in recording there are so many variables. And likewise, when I get off the road after a long string of concerts, I’m very anxious to get into the recording sessions to lay it down and freeze it where I’ve got it, because that’s a really rewarding process too.”

Kondonassis says she lets her passion dictate the recording projects she chooses. “I don’t think I’ve ever done a project because I thought I should do it. I don’t have an incredibly obscure musical taste, and I find that if I have fun listening to something, if something inspires me or stimulates me, then I trust my judgment. I find that if I like it, it will probably find a decent audience.” A look at the repertoire Kondonassis has recorded from album to album will take you on a bouncy ride throughout genres and musical periods. But it’s the variety that sparks Kondonassis’ fire. “I think that’s what keeps my engine going. I know many people find great passion going really deep into one genre of repertoire, but what really excites me is finding something slightly new and out of my comfort zone—maybe it scares me a little bit—then charging forward and figuring it out.”

Perhaps this helps explain Kondonassis’ sustained level of success over the last 26 years—her willingness to go all in and her attention to detail have remained rock solid, while the world around her has changed at a break-neck pace. “It’s been an interesting swath of time since 1993,” she says. “There’s almost nothing that hasn’t changed since then. Despite being a change resistor myself, there is nothing that’s going to stop it, so you might as well climb on board.” •