As a long-time “harp sister” of Heidi Bearcroft (née Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton), I’ve had the privilege of experiencing her artistry, integrity, and resilience firsthand. In this candid conversation, Bearcroft shares how the challenges and opportunities she encountered early in her career helped her cultivate a transformative perspective on mental and musical well-being in her life as a seasoned performer, passionate educator, and devoted mother of two.

Harp Column: Let’s take it back to 2009. I’m new at Juilliard and you are a first-year master’s student, and I am completely starstruck. You had just won the American Harp Society Competition’s Young Professional Division, and you were giving recitals everywhere. I was a little nerd and had no idea what to expect. You were so warm and friendly and kind, and truly, you were one of my friends from the very beginning. I have such good memories of that. Thinking about that time you spent in New York, how do you think it shaped your early career development, being in New York City for six packed years?

Did I choose this career because my entire family did it? What was my true connection and reason behind wanting to be a performer?

Heidi Bearcroft: Actually, I spent seven years there because my first year at Juilliard, which was 2004, because I had tendinitis and took six months off of playing. I moved back to Pittsburgh and didn’t rejoin musical life until I went back in September of 2005 for sort of a redo of my freshman year. So it started a little bit rocky. I’m age 18. It’s my first time living away from home. My teacher growing up was my mom, and she largely remained my teacher until I went to Juilliard. Although I did have a few other teachers I worked with informally, my mom was always my greatest resource. It was my first time really studying with somebody without my mom’s influence at all. It was a huge transition, and I think I was overwhelmed. New York was such a big city compared to Pittsburgh, and it was a little bit rough at the beginning. Also, I was asking questions like, why did I choose this career? Did I choose this career because my entire family did it? What was my true connection and reason behind wanting to be a performer? The whole first year, including the time that I had to go back home, was spent thinking about reasons why I chose that path.

HC: Thank you so much for sharing, because we look at someone like you, who has an amazing career and family, and may think it’s all been easy. I think it’s really important for people to know that there are periods where you have to overcome some pretty serious adversity like you have. What personal strengths did you rely on to get you through that period?

HB: It was one of the first of a handful of times that I was forced to turn inward and become self reflective. That’s something that I had never done before. As an 18-year-old, I feel like those are huge questions to answer—Why am I doing what I’m doing? What do I want with my life? I think [asking those questions at that age is] really unique to musicians or other elite career paths. It’s not common for a teenager to know what they want to do with the rest of their life with any sort of clarity. And yet, that is what’s required of a music major, or a dance major, or an athlete. Having to answer those questions and look inward is not anything you can prepare yourself for. I was really blindsided by the tendinitis, and I think it came about because I had taken some time off over the summer before matriculating at Juilliard. The stakes were higher than I had experienced. I’m surrounded by greatness. My teacher was a role model. I just went from zero to 100 in terms of practicing and expectations on myself and perfectionism and all those things. I injured myself because I didn’t pace myself. Moving home forced me to slow down. It forced me to connect with my true self. I had to slow down and figure out if this was what I wanted to do with my life. It was a really tough time.

HC: I think what you’re describing is what a lot of people go through to varying degrees in that transition, not only just to college, but also stepping out of that safety bubble of home and into the “real world.” Having to make that serious commitment as a young person creates a tremendous amount of pressure.

I think when or if you become clear on your “why” you chose [music] and you cultivate compassion for yourself when you make mistakes, you’ll become a more compelling performer.

HB: The way that I was able to answer those questions came about from working with a fantastic Alexander Technique teacher. I even saw her twice a week sometimes. The way in which we worked was much more emotionally focused, exploring how emotions and memories or triggers are all stored in the body and how pain can be reflective of a mental state. I had tried acupuncture and braces and magnets and physio, and none of that touched the emotional reason behind the pain. Without going into too much detail of it, I emerged from that experience asking myself, why do I play? I came to the answer: I play because of the sound. I love the harp because of the sound, and the sound is what motivates me. It’s such a simple answer, but I gained clarity on that. Then when I started to play again, [I was able to] really let the joy of the sound come through me and fill me inside, instead of focusing on the perfectionism or the competitions, or even micro goals. Understanding the bigger picture of choosing music because I love the sound helped me to drop back into my “why” and kind of reset.

HC: It sounds like, first having that deeper connection with the body was your avenue to then explore deeper emotional components of your playing and of who you are.

HB: Yes, and it helped me individualize myself from this long lineage of musical giants in my family background—my grandfather was Professor Emeritus of bassoon at Eastman. He played with the Rochester Philharmonic and the Cleveland Orchestra. My aunt is still in the first violin section of the San Francisco Symphony. My uncle was concertmaster there for 18 years or so. My mom is still principal harp in Pittsburgh. My dad was co-principal oboe in Pittsburgh. One of my grandmothers was a concert pianist and the other a professional cellist. So I come from a line of greats, but it was important to realize what my own motivators were and to fall in love with the instrument again, not just because I was good at it, but because I realized I had something to say and something to give back to the musical world.

HC: Yes, it sounds like you worked really hard to find your own voice.

HB: I did, yes.

HC: Where do you think the music world could improve on a more systemic level of supporting mental health, especially for young musicians?

HB: I love talking about mental health, and I know you do too, that’s why I’m so glad we’re doing this. I believe mental health is a foundation of being able to be a performer and to be a human in the world. Being self-attuned and self-reflective, to me, is the greatest gift we could give ourselves. As performers, we’re trained to be self-critical. We are trained to strive for perfection, to out-do ourselves. The inner critic is valuable because it gets us to where we are, but it can be so pervasive that it paralyzes us and it seeps into every area of our life. So for me, in my own journey cultivating a practice of self compassion has been equally, if not more important than solely focusing on self improvement. I know that doesn’t answer your question, but I just want to say that as sort of like a mission statement of my hierarchy of what’s important in my life.

HC: Yes, absolutely, human beings first.

HB: Yes, grace and a sense of self first. But you asked how can the music world improve? I think we’re moving in the right direction. With respect to mental health, the stigma is lessening. I don’t know what it’s like at Juilliard now, [when I was there] there was a counseling office, and, at least in the harp studio, I felt quite supported. I was able to be really vulnerable with Nancy [Allen], which I’m grateful for. But I hope that more and more mental health resources are not just available, but talked about and encouraged. You feel less alone when there’s a community. And I think that so many people struggle, and it’s not talked about, which is a shame because it’s so human. The more that we shine light on it, the more we are able to step out of the shadows of shame or isolation. You’re trying to be the best, and you want your teachers and your peers to think the best of you. I spent a lot of time hiding various anxieties or depressive moments from my peers, but I think that if I had had the courage or the encouragement to share, I would have found so many other people felt the same way.

HC: Yes, so true. I absolutely used the free counseling services at Juilliard. And I’m so glad, because accessibility is a big part of this conversation. But also what you’re saying is it’s important to create an environment where it’s safe to openly have these conversations. And healing the self physically and emotionally will help us function as happier and more joyful human beings.

HB: Yes, and to bring it back to the performance space, I think when or if you become clear on your “why” you chose [music] and you cultivate compassion for yourself when you make mistakes, you’ll become a more compelling performer. When you’re on stage, or when you’re making a recording, or putting your art out into the world, the audience can tell. There’s a level of transparency that you give when it’s really coming from a place of joy and not obligation. I believe you’re able to perform more authentically when you’re of sound emotions and mind and you remove your ego from it.

HC: What’s the best advice you’ve ever received on this topic?

HB: I think it was 2008 when I competed in the Victor Salvi Awards in Chicago, where we played the Norma Variations and Le Jardin Mouillé by Jacques de la Presle. There were so many competitors that there were two days of auditions, and I drew the last slot—the final competitor. These poor judges had heard Norma 39 times before me. It’s such a demanding piece physically, and requires a lot of stamina. I remember being backstage and my nerves were high. My incredibly supportive dad was there with me, and he looked at me and said, “Heidi, remember that you’re doing this because you love it.” Immediately, so many of the nerves melted away. It became my little mantra. I repeat that to myself when I’m going on stage with nerves pre-competition, pre-audition, pre-Nutcracker solo, or whatever it is, I always try to come back to remember, you’re doing this because you love it. It’s not about nailing all the right notes and the what ifs and the perfection. It’s not about you—it’s about expressing something to the audience. It’s the best advice I’ve ever been given. Another piece of advice that I give and I tell my students is that nerves and exhilaration register in the same way physiologically in the body, so it’s super easy to confuse fear with excitement. Remember that nerves are normal and it’s okay to have them. Nerves actually mean that you care and you want something to go well. It would be weird if we weren’t nervous, and chances are there’s some excitement and looking forward to playing as well. Allowing yourself to feel however you’re feeling without fighting it is the best advice I could give.

HC: Yes, it’s so important to have that awareness and understanding of how the nervous system works, because otherwise you’re going to think “something’s wrong with me.” But your body’s doing exactly what it’s supposed to do.

HB: Yes, it was made to do that! But with the fight or flight reaction our brains perceive danger because of our physiology. So it’s important to be able to slow down, allow the thoughts or reactions, and then remind yourself: “I’m safe. I’m doing something I love. I’m doing something that I feel so strongly about doing.” I think it just cuts through so much of how we get in our own way.

HC: I love that all came from your family. So coming from a musical family, what role do you think music will play in your kids’ lives?

HB: Well, when my daughter, Shelby, who’s four now, was born, Lyon & Healy sent me a tiny pink harp. My husband opened the package, and he was like, “What is this?” I said, “I swear I had nothing to do with it—it was a surprise gift.” It was so cute. But he’s like, “Oh no, we’re writing her destiny!” But Shelby is so musical—she is obsessed with music. We listen to music all the time. She just started piano lessons a week ago, and when I or anybody asks her, what do you want to do when you grow up? She says, “Well, Mama, I already have a harp.”

HC: She’s so practical! [Laughs]

HB: I know, and I try to prompt her, “Honey, you could be an author, you could train horses, you could play the trumpet. You could be a garbage woman.” These are real words I’ve said. And she says, “No, Mama, I already have a harp.” So in her mind, she already is a harpist.

HC: It’s just inevitable. [Laughs] Speaking of kids, the last time I saw you in person, you were pregnant with number two, sweet Mickey. I’m curious, can you tell us a little bit about what the transition was like coming back to work after you had kids?

HB: When I had Shelby, it was in the height of the pandemic, so I wasn’t working. I was lucky to have an extended maternity leave, because there was no work to come back to. So it was a real soft entry into the world of being a musician and mama. Fast forward, I got pregnant again, and it’s really challenging. My second pregnancy was really hard, and by the end, playing music was the only thing I could do because I was so sick and in so much pain, I was on crutches by the end. When Mickey was born, I took the allotted time off, but it felt completely different coming back, because I had a different experience with Shelby. It was harder than I thought it would be, probably because of hormones, and I just couldn’t predict how it would feel. Having two kids is very different than having one kid. But I will say two things. The first is that going back to work was amazing because it felt like I was reclaiming part of myself and my identity outside of being a mom. I was able to come back to being great at something other than parenting. The second thing is that having kids has given me so much perspective. Before having kids, I would think “Yes, this fast passage in “Mercury” in The Planets is coming up…I’ve got to nail this.” I’d spend a lot of mental energy thinking about that outside of work, but after kids, you come home after a particularly hard passage or performance, and you’re back to diaper duty and have Cheerios in various crevices. [Laughs] It’s so humbling realizing that nothing is that serious.

HC: It puts everything into perspective, for sure. I remember a conversation with Nancy [Allen] where I said, “Oh, I don’t think I can play tennis, because I might hurt my wrist.” And she looked at her own hands, almost in horror, and said, “Oh, well, these hands have done everything. They’ve painted walls, they’ve changed diapers…” It sort of simplifies things.

HB: Yes, it really does. It distills what’s important. Like I was talking about earlier, it removes the ego and really aligns your values and reaffirms your reason for being a performer.

HC: And now you have been in the Toronto Symphony for over a dozen years.

HB: I’m starting my 14th year. I love getting older. I’ll be 39 in the summer, and it’s great.

HC: You and I, we both love our big, bodacious orchestra parts. What would you say have been some of your most blockbuster orchestral experiences?

HB: Well, one that comes to mind is when I was playing with the Pittsburgh Symphony, subbing for my mom when she was sick. We were playing Mahler 1 all over Europe. I would say Mahler is probably one of my favorite composers. At the end of Mahler 1, the whole horn section, all eight or nine or however many stand up to play, and in every performance I was just brimming with pride and gratitude for getting to do what I do in the orchestra, just being quite literally filled up with the surrounding sound on stage, in Europe no less.

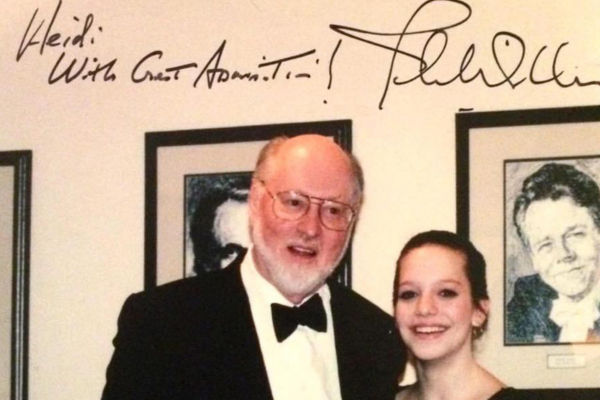

Another memorable experience was with Itzhak Perlman. There’s a CD of John Williams’ music with the Pittsburgh Symphony and Itzhak Perlman called Cinema Serenades. I listened to it a lot when I was younger because my parents were on it, and they loved it. So this is one of my favorite CDs. I can’t remember what year it was, but I got to play that music with Perlman and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. It was a full circle moment from listening to that music when I was 12. In my parts, I have all my mom’s markings, so seeing that was really meaningful as I was playing that music that I grew up listening to.

HC: How would you describe the role of an orchestral harpist as compared to other positions in the orchestra?

HB: Well, we’re a solo instrument, of course. I think there’s a lot of pressure on harpists, mostly because the preparation is so different from any other instrument. Knowing your part inside and out and working out page turns and putting in fingerings and pedalings and figuring out enharmonics or rewriting a passage—those are just things that, while I love them, my section string player friends don’t and won’t ever have to do. I think it’s akin to an oboist spending hours upon hours making and perfecting reeds. It’s an incredible time commitment. Few other instruments have that sort of prep outside of even the first rehearsal. The actual on-the-job musical role is cool because there’s no one concrete role. The harp is so malleable, and sometimes we’re playing solo notes with piccolo or celeste to give a sparkle. Other times we’re playing these rich, low bass notes with bass trombone and second or fourth horn and the bass section, giving that grounding stability to the harmony. And then other times we’re completely soloistic, as in Tchaikovsky cadenzas or Smetana Ma Vlast. Our range of roles and colors is just awesome. We also have to be so adept at blending and knowing when we’re adding color versus texture and knowing when we step into that soloistic role. So we have to be real chameleons in terms of how we prepare and perform.

HC: So well said—there’s your job description for an orchestral harpist.

HB: I just want to give a shout out to Gillian Benet Sella in Cincinnati and Emily Levin in Dallas for the tireless work they’re doing to bring more awareness to the value of orchestral harpists within the context of an orchestra. Harps are underappreciated because of the instrument’s role historically, but completely inaccurate now and with all the contemporary music we play and movie scores. Harpists are very hardworking and integral members of an orchestra.

HC: It’s such an important ongoing conversation.

HB: Yes, and we’re lucky to have those people championing us.

HC: Well, switching gears a bit, in addition to all the performing and mothering you’re doing, you are also teaching in Toronto. Tell us about your approach to teaching.

HB: I’m on faculty of the Glenn Gould School at the Royal Conservatory, teaching orchestra rep and coaching chamber music. I also have a very small private studio, and I just try to be super down-to-earth and peer-like with my students, because I really do feel like we’re all in it together. I’m not better-than just because I’m older; I’m still learning. I got some markings from one of my students a couple days ago for a cadenza, and I’m really excited to try, because I’ve never thought of it that way. I really like to think of it as collaboration, and it’s also so affirming when I’m able to give advice about nerves or a way of practicing that resonates with somebody. It also reaffirms how I should be practicing too. I don’t give any advice that I don’t also heed myself. I also put a lot of emphasis on total health, and I really care about how my students are doing holistically, not just musically. I spend a lot of time teaching about the energy behind notes that we play, the direction of a phrase, and breathing. Obviously, we don’t have to breathe in order to make a sound, but we need to really be able to breathe life into phrases. •

Grin and Bear It

Favorite post-concert snack: I need something salty and then also something sweet. The first thing that comes to mind is popcorn and Terry’s chocolate orange pieces. Also, prosecco.

Favorite harp duet: Oh, that’s hard—maybe Parvis by Bernard Andrés.

Son’s favorite lullaby: I made up music to a book called Love You Forever by Robert Munsch. The lyrics are printed in the book, and I just made up a melody for that. I sing it to him every night. “I love you forever. I like you for always. As long as I’m living, my Mickey you’ll be.”

Desert island composer: Mahler, just because the range is so broad—I could get the comical and the heart wrenching, and there’s everything in there. Also, his pieces are so darn long that I feel like I’d have a lot of material with which to marinate on my island.

Guilty-pleasure TV show: Honestly, I don’t watch a lot of TV because of children, but I love true crime docuseries.

Favorite Canadian word or phrase: Eh—I use it all the time, and people say, “Wow, you sound so Canadian.” But it really is a very useful phrase, eh?

Favorite way to unwind: A breathing exercise that I love. Breathe in for four, hold for one, breathe out six. It’s the fastest way I’ve found to regulate my parasympathetic nervous system.

Hockey or curling: Neither. I’m not a sports person. I tried curling once, and I did not connect with it. I just went to a Blue Jays game the other day, and that was fun. I just enjoy the energy in the stadium. I’ll root for my team if it’s doing well, but beyond that I could not care much less. [Laughs]

Sequins or tie-dye: Sequins—I am obsessed with sparkles. Give me all the glitter.