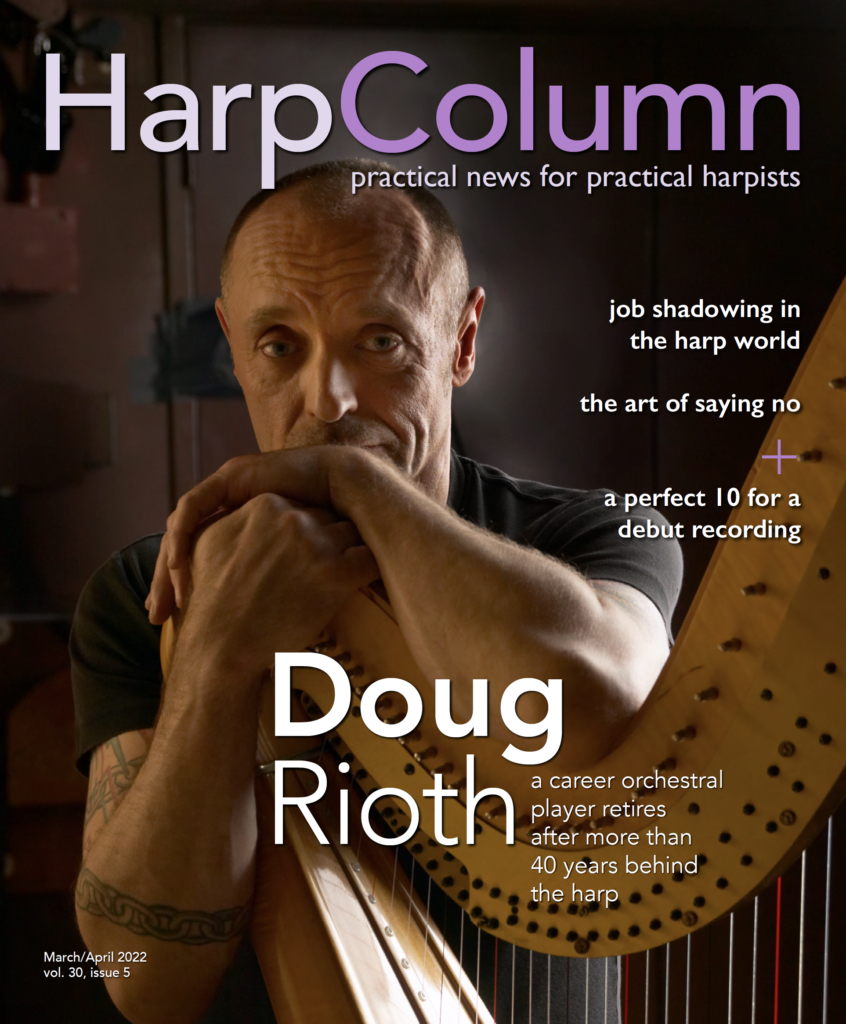

9/10

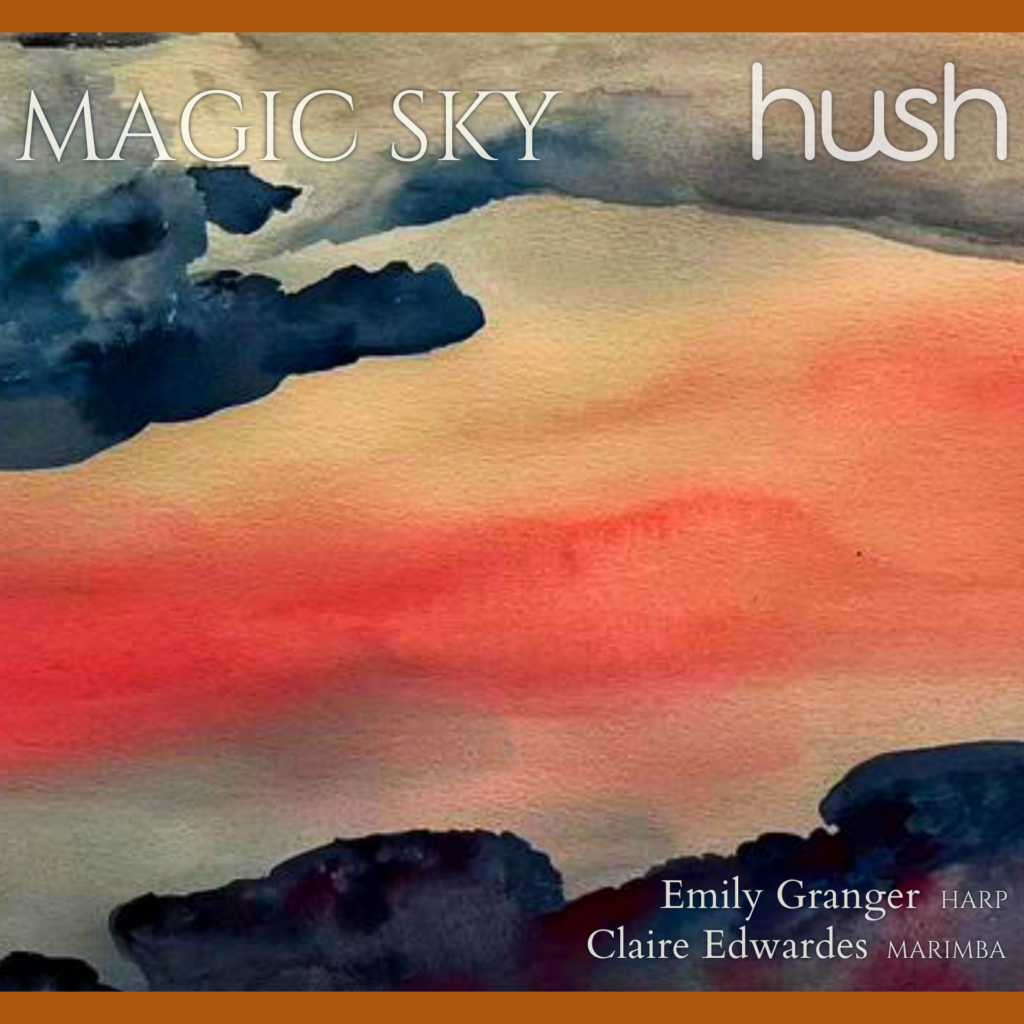

Emily Granger, harp. Avie, 2022.

American harpist Emily Granger is quickly establishing herself as one of the leading harpists in her adopted home of Sydney, Australia. Interestingly enough, I became friends with Granger through backpacking. Though we have only shared our adventures on trail through the internet, it comes as no surprise that her debut solo album would explore themes of travel and new cultures, as well as what it means to be together and alone. In Transit (to be released March 11) is a superb collection of contemporary works from both sides of the globe and the ideal repertoire to showcase Granger’s vibrant musical personality.

In Transit is a superb collection of contemporary works from both sides of the globe and the ideal repertoire to showcase Granger’s vibrant musical personality.

The title track is by Australian composer and Granger’s fiancé Tristan Coelho. It sets the mood of momentum versus limbo, and Granger plays with expansive expression. The repeated patterns mesmerize, while fits and starts demand reflection and redirection. The two met in the rugged Blue Mountains of New South Wales, an escarpment of spectacular beauty. It’s home to The Old School, a former children’s school and now an artists’ colony. Coelho’s short work of the same name recollects the voices of children from times past and is richly evocative.

Also dream-like is Australian composer Ross Edwards’ The Harp and the Moon. He describes falling under the spell of the harp and his writing simply flowing naturally, and it feels equally alluring from Granger, as if a spontaneous exclamation of joy under a magical night sky. Two works explore complex rhythms beginning with American composer Laura Zaerr’s River Right Rumba, the repeated pattern lifted from a Guinean drumming pattern, and Australian composer Sally Greenaway’s tango, Liena. Granger plumbs the rhythm’s delicious ability to move us, both on an emotional and literal plane.

Most interesting in breadth is Libby Larsen’s Theme and Deviations. Always experimenting, the piece is a play on the traditional form where she comments on a seven-measure statement, relating to it, but never quite repeating it. The first deviation is a suggestive melodic fragment followed by a dance that allows Granger to display her technique. Next is what Larsen calls a “study in pedal shifts,” full of mystery and atmosphere, leading into a “musical dart,” an intense and barbed presto. The final deviation puts color and line to the test, and sets the tone for the following work, Elena Kats-Chernin’s glorious Blue Silence. Arranged by Granger, the piece was written as a palliative of a calming meditation for Kats-Chernin’s own son who lives with schizophrenia. Granger evokes the warmth and comfort of a favorite shawl.

It is in Kate Moore’s highly technical Spin Bird, a retelling of the striving Jonathan Livingston Seagull, that Granger shines. Moore writes that the work’s challenges remind us that the “power over oneself is better than a thousand years of power over others.” True, but it is best when accomplished as Granger does, soaring confidently into the sky.

Sally Whitwell was trolled by a bully who accused her of never once using a diminished chord. Finding humor in the metaphor, she named her solo harp work Undiminished. Granger emphasizes the dignity and grace of this powerful short meditation, her full-bodied tone epitomizing going high, when others go low. Similarly, she draws upon her glorious and sonorous sound in the stillness of Augusta Read Thomas’ Eurythmy Etude “Still Life” and Nancy Gustavson’s pure ecstasy in Great Day.

Ending with the tender lullaby The Nightingale by Deborah Henson-Conant, Granger rounds out this wonderful collection by reminding us why we love the harp so much, and why we love music.