—by Lynne Aspnes and Heidi Surniolo

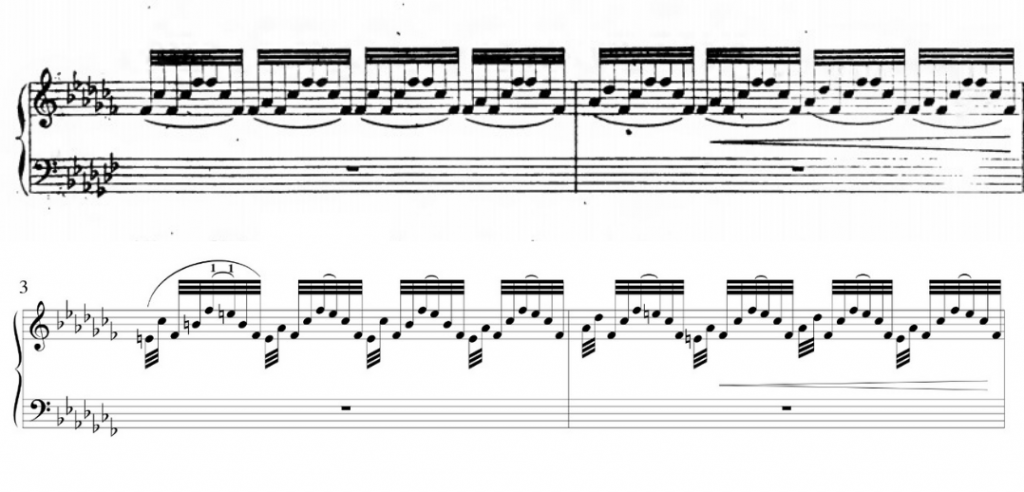

Ed.—Just after the New Year, I received a text message from a harp friend and college classmate, Heidi Sturniolo. She texted our former teacher, Lynne Aspnes, and me to tell us how much she was loving Gayle Barrington’s edition of Tournier’s Vers la source dans le bois, a piece Heidi had played when we were undergrads at the University of Michigan. She sent a photo of both her original part and her newly downloaded edition from Harp Column Music, side by side on her music stand. “The best money I ever spent buying music I already own,” she wrote. “Yes. I paid you $16.95 for music I already owned. It’s a thousand times easier to read. The enharmonics are such a nightmare in the original.” What followed was an impassioned debate between former student and teacher, which illustrates the decisions harpists increasingly face between the ways we have always learned how to do things and shortcuts that modern advances afford us. Where do you come down on this debate? Go online to harpcolumn.com and let us know.

Lynne: Sure it’s easier to read, but there’s a learning trade off that we have to take into account along the way. Traditional theoretical notation may look daunting on the page, and having to translate terms from their original language might seem an exercise in futility, but for me, this is an important stage in the learning process, one that informs students of the history of our discipline. Scientific studies support the concept that learning made easy can be learning made impermanent. My old-school approach definitely defends the idea that learning made a challenge may contribute to deeper learning of the entire process. Learning made simple might get you there faster, but possibly with fewer long term benefits. And then there’s the age old trope of taking the high road versus embracing shortcuts. We are in an age of evolution in music notation, to be sure. But are we prepared to dismiss the frequent complexity of the traditional, in favor of the expedient?

Heidi: I almost left you out of this thread for that exact reason, I know. Ethically I had an issue, but seriously, I just played the first several pages at a nice clip because I didn’t have to convert every other red circled note. The eye scramble is the biggest reason I haven’t returned to this baby in 20-plus years.

Lynne: Right, and that’s convenient, and it’s got to feel good: getting through multiple pages of music fast, and feeling good about your accomplishment. Consider the benefits of giving in to the eye scramble, though, which I think you mentioned you had the first time around. When the brain has to slow down enough to actually figure out what’s supposed to happen next, that allows for a mental processing of information before sending messages to the muscles. In the end, it’s the difference between pure muscle memory and integrated mental and kinesthetic memory. Fast is fast and sure, there are times when cramming has to happen. Forced learning can come in handy in the short run, but there is evidence that for deep recall learning, a slower initial process stores the information we need more effectively while also helping us to relate information across platforms. I am an abacus learner in a microprocessor universe, I know. A veritable T-Rex standing on the edge of extinction. But I believe there are huge benefits to be had by engaging with the intellectual exercise of the learning process itself. In this specific case, I know you own both copies of the music we’re talking about. When you revisit a piece this new notation makes the music come back fast for you. When it comes time to teach this piece to the next generation, you’ll have to choose: do I stick with the stone tablet version with the students first time around, stretch their brains a bit more with the alternative universe of traditional notation, or will I let them zoom ahead with the platform that conforms to what they are used to seeing?

Shortcuts exist, and cramming is always going to be part of a student’s path along the way. But shortcuts and cramming will let you down in the clutch.

Heidi: Okay. For sure, my “nice clip” tempo had as much to do with residual muscle memory from my teenage years as the heightened readability of the edited score. And I fully recognize that learning something in depth is far more valuable than surface learning. But you are making such a hard sell for these enharmonics! You still have to learn the notes, one way or another. Just because the notes are enharmonics doesn’t mean they are special snowflakes. A note is a note, and you still have to learn it, whether it was put on the page by the composer or the editor. Would you say no to a Sherpa taking you up to Mount Everest?

Lynne: Nope, because he’s the professional and knows the ropes. Without that expertise I’d be lost. So I guess my equivalent is that we’re the professionals. The thousands of times we’ve traversed that enharmonic mountain help us keep the amateurs from perishing on the slopes.

Heidi: I 100-percent agree with you. I think the edited music is a supplement, and it wouldn’t be the only copy I would own, and I don’t think I would teach from it. I would make my student suffer like I did. It is important to see the enharmonics, but for me, now, being able to just play it is nice. It’s also equally important to qualify my stance…my grumbles are directed specifically towards Vers la source dans le bois, not all enharmonics in general. In the normal course of playing, I totally pull on my big girl britches and just calmly circle an enharmonic. If I’m feeling reckless or really sassy, I don’t even use a red pencil. But Tournier crossed a line with this one. It’s like he bought a rail ticket to a far off, esoteric composer fairyland. It’s brilliant, but boots on the ground? The edit makes sense. You still have to put in the work. You still have to learn the notes and create music, you just don’t have to deal with measures where nearly a third of the notes are substituted. This is the hill I will die on.

Lynne: If Orpheus had followed Google Maps, where would the music world be? It’s a new year and hopes are high. We’re all thinking, “This is it, this is the year I’m going to do ____________ better than ever! I’m going to be patient all year, keep my cool at every gig, plan ahead, never be caught without a full set of replacement strings, move mountains with my pinkie, and learn all the new music I’ve wanted to learn forever! Whatever we dream seems like it can come true in January each year. Not so fast, my friend, not so fast. Science tells us that for the most part we are just riders in the sea, being born aloft by the daily demands of life, working hard to keep our heads above water. All of those lofty expectations of newness wear off with the sixth snowfall in January when the handle falls off your favorite shovel and the city plows in the mouth of your driveway. And there you are, stuck in the house when the practicing instinct takes over and you think, “I’ve got all day; I can do this!” Like television home rehab—in 30 minutes I can knock out a designer kitchen, add that pool, re-tile a historic roof, and landscape like a pro. Then reality hits: we put in a half an hour and start to wonder, “Isn’t there an easier way? Where’s that silver bullet that makes learning music as simple as…well, so simple anyone could do it.”

Ah, and there you have it. Learning—long-term, durable, deep learning—is never easy and cannot be accomplished by taking shortcuts. Deep learning involves a lot of experimentation, a willingness to go down more than a few rabbit holes, loads of determination and discipline, mountains of creativity (to get us to that harp bench when absolutely anything else seems more enticing), the ability to laugh at oneself (a lot) along the way, and loads and loads and loads of time. Shortcuts exist, and cramming is always going to be a part of a student’s path along the way. But shortcuts and cramming will let you down in the clutch. What will never disappoint is genuine knowing: so well known that your brain and fingers and voice all move as one when it comes time to reproduce your practicing results.

In 2019 let’s strive to take the high road, every day. Let’s commit to deep learning, to experimentation, to never yelling at ourselves for not getting it right the first time. Let’s laugh at our foibles along the way, encourage our better selves to keep on trying, to keep sitting down on that bench and, in the end, to learning more than we ever thought we could because we were willing to take on the hard lessons. Being really good at something takes all we’ve got, and we’re willing to give it everything we’ve got because we’re never going to shortchange the music, never.

Heidi: I’m giving you a respectful slow clap. In all sincerity, you’ve earned the last word with that. But this is where I am. Had I read this debate between you and someone else, you totally would have won me over. Take shortcuts? Not me (usually). But now that I have this edit, you’ll have to pry it out of my cold dead hands before I play off the original score again. •

Lynne Aspnes is the president of the American Harp Society and professor emeritus of the University of Michigan.

Heidi Sturniolo is a professional harpist in metro Washington, D.C. She holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan and a master’s degree from the Cleveland Institute of Music.