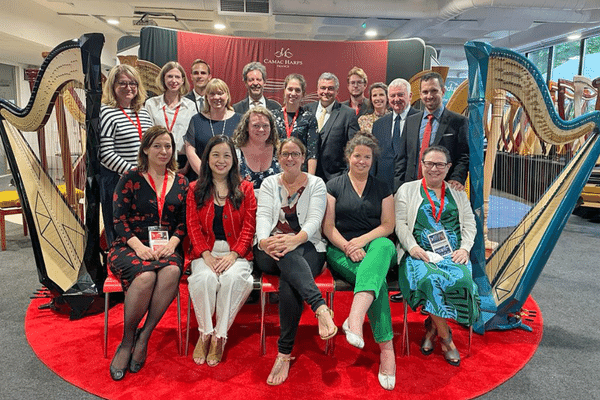

Building a harp is difficult. Building a good harp is even harder. Building lots of good harps that keep you in business for 50 years? That’s something to celebrate. And that’s just what French harp maker Camac did this past October as it marked its golden jubilee with a festival and a new pedal harp model named, what else but the Jubilé.

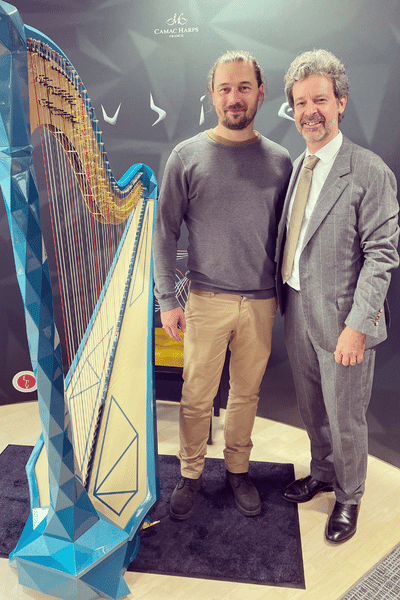

We sat down with Camac’s president Jakez François and CEO Eric Piron in their Paris showroom to find out the secret to their success and what motivates them to keep producing new instruments.

Harp Column: Congratulations on Camac’s 50th anniversary. We’re curious what you think Camac’s greatest achievement is thus far.

Jakez François: The first thing I would think of is that we are still there. One of the big events in the history of our company was the passing of Joël Garnier—he had such a strong personality, and he was the founder of our company. Understandably, many people were concerned about how we could continue to survive after such a strong personality passed. This was probably the biggest challenge we have had to face. But fortunately we were very well prepared. His passing was not such a surprise. I had been working with him for 12 years, and in his final year we did what we had to do for the transition. He was very wise to introduce me to Eric a few months before his passing, and this was his vision of how the company would continue after him. He was very right. Celebrating 50 years of Camac is, of course, celebrating what [Joël] has done and what he has founded. Our single best achievement is that we have continued in his spirit of innovation and developed the company with the harpist’s needs in mind. Joël was very focused on innovation—sometimes a little too much, maybe, because he had a passion for that. I thought we should be a little less extreme, trying to find the middle ground between what could be improved and what should be kept from our tradition, in terms of materials and how we build the harps. This is how we created what we call the “new Camac sound.”

HC: So much has changed in technology in 50 years since you started. What are you doing now that you couldn’t have done when you started making harps, and what are you doing the same way as when you started making harps?

JF: It’s an interesting question because it also gives me an opportunity to give credit to what Joël has developed. Joël had a very radical view of his innovation. He had to make harps different from what existed because he didn’t want to do what others were already doing. He wanted to do better and to do it differently. Our philosophy is that to do better doesn’t always mean to do it differently. There are very good things in the tradition and also very good things in innovating. What we kept from that early innovative time is the structure of the harp that Joël developed. He had a very smart idea about the structure of the harp, which is basically the connection of the column to the sound box, which is extremely strong and reliable. His design solved a lot of the problems that happen when a harp ages. He also knew that harpists relied on harp technicians, and he wanted to make their lives easier. So he designed this very clever tool (which Camac is famous for) that helps a non-technician adjust the length of the connection between the pedals and the mechanism, which is the foundation of any harp regulation. We have kept this structure, this special regulation tool, and of course, most of the designs, which make the action easy to regulate. What we have not kept is most of his research on composite materials to create a lighter harp. Not that I don’t think it’s reliable, but after Joël passed, I have worked on getting the sound that I have in my mind, and I realized quite quickly that the use of those composite materials was a dead end. I couldn’t approach the quality of tone I had in mind by using this kind of new material Joël was so fond of. So we had to get rid of most of these ideas and come back to a very traditional way of making harps, which is using wood, and not just any wood, but types of wood that harp makers and instrument makers have been using for centuries.

HC: Camac produced its first pedal harp about 35 years ago. Since then, you’ve continued to make changes to the functional design of the harp. Do you think you’ve perfected it, or is there still room to evolve and improve?

Eric Piron: Jakez is working every day on the mechanism and every screw and everything. I think there is not one piece that we are not redesigning all the time. That doesn’t mean that we are changing everything, but we are always trying to improve the quality of each screw, each material. It’s always a work in progress to make it better.

JF: The functional aspect of the harp is very interesting because, in fact, there is very little that we can change to the functional aspect of the harp in terms of the player. Because if you change anything on the harp, then it means that the player has to adapt to it. I’m aware that Camac harps are a bit different from others. One change I forgot to mention earlier that we kept is our ergonomic string arrangement. Joël had this idea to slightly change the position of the strings to allow more room for the right hand without changing the vibrating lengths. This is something quite genius, because you cannot change the vibrating lengths of a harp’s strings, otherwise it will quickly cease to be harp anymore. But by slightly changing the angles of the top third of the register to make it more playable, a side effect is that it gives more room for the right hand in the top of the harp. This is something that harpists really appreciate. We are very aware that it may be surprising when you play a Camac harp for the very first time. But with a few minutes to adapt, we find that the benefit is so big that it’s sometimes difficult to come back to a more conventional design.

HC: No creative process is without its ups and downs. How do you handle those setbacks when things that you have tried over the years have not worked out as well as you would have wanted? How would you handle that type of negative feedback?

JF: Which negative feedback do you mean? I cannot even think of any. [Laughs] Before we decide to change anything on the harp, we will have extensive testing to make sure. But, in fact, I cannot think of many examples that would answer these questions, because we have not made radical changes to the instrument since the harp that Joël designed. From a functional point of view, we have not changed anything. The only thing we have really changed in a generation is our focus on the quality of sound. As Eric said, I have redesigned every single part of the harp, but the only goal was to make the sound better. When I say “better,” I mean to get closer to the sound that I have in my mind, which is the sound we have in our genes from Erard, the French sound—the quality of tone and projection, and the carrying properties of the sound in the concert hall. This definition of the “French sound” applies to any kind of instrument.

EP: Jakez has been working on defining the DNA of the French sound, using his background and the older harps in our collection. There was a break in between the time Erard stopped making harps and our generation, so he really tried to take that DNA and figure out what the sound would be if it had continued from that time period until now.

HC: How would you describe the French sound?

JF: Oh, that is the question. It’s an interesting question that is often asked because it’s a quality which is shared among many instruments—not just the harp. I’m in a group of French instrument makers, and we all share the same vision, which comes from our tradition, mainly from the 19th century. So from Erard for the harps, but from Buffet Crampon for the clarinet and Pleyel for the piano. They all have the same kind of ideal sound. I would use the words precision, full-bodied sound, and projection to describe it. It’s very interesting, though, because every musician, every instrument maker uses the same words to describe the ideal sound. I was once in a round table meeting with musicians and instrument makers about the language and words used to describe the sound and the music. It was an interesting experience because, to start the round table, they asked each musician to describe their ideal sound, the sound they have in their mind which they are looking for. They all used the same words—the harpsichord player, the saxophone player, the harpist, the guitarist, the pianist—they all described the sound using the same words. Of course there is nothing in common between a saxophone and a harpsichord, but they describe their sound the same way. It is impossible to describe in words what the French sound is. I think any harpist would use the same words to describe their ideal sound, even if they would be very different sounds, in the end. But the French sound is really what connects us to the tradition of the golden age of French instrument making and playing.

HC: Do you feel a responsibility as the first modern maker of harps in France since Erard to work towards that ideal of French sound?

JF: I feel a responsibility to the harpist who is trusting us by choosing our instruments. My responsibilities are to give them the best quality of instruments, to build the most reliable harps, and to be able to give the best service during the life of the harp. This is really a very deep feeling of responsibility I have towards the harpist. But it’s not a responsibility, it’s just the pride I have to be continuing this tradition of making harps in France.

HC: Camac is unique in having a harpist at the helm. How do you think that has affected your approach to instrument making?

JF: I think that having spent all my life playing the harp and my connection with the harp coming from my childhood have given me a very deep understanding of the instrument. I’m not an engineer. I’ve not done long studies of any subjects. I’ve just spent my whole life making music and playing the harp. I feel a very deep physical connection to the instrument. Does it make a difference? There are very famous harp companies who have been founded by non-harpists, and they are all very good. But maybe there is a little added value in the fact that I am a harpist, because I know the feeling of having to rely on someone else to maintain your instrument.

I mentioned before that the main responsibility I feel is to our customers, to the harpists who play our harps. Harpists rely on an instrument to play sharps and flats—you cannot do it by yourself. Most other instruments can. When you play the violin, if there’s something that’s out of tune, it’s because of your technique, not because of the violin maker. If your piano is out of tune, you just go to the local piano tuner, and you can even check on the internet to see who is the best in your city. When you are a harpist, you are very lucky if you have a technician in your country or even on your continent. So you rely on the harp maker you have chosen. All harp companies make great harps, otherwise they would not be in the business for very long. So what makes a difference is, of course, the sound, which is absolutely the number one priority. But after this sound, I think the main aspect is the service that you get from the maker you have chosen. As a harpist, this is what I feel—a deep understanding of the instrument, because I spent my life making music and playing the harp, and knowing the feeling of relying on someone else to maintain your instrument so that you can really play it.

HC: Let’s change gears and talk about the design and aesthetics of your harps. Each new model you produce looks vastly different from the others. How do you choose the designs and the designers you work with on new models?

JF: After Joël passed away, the first design work I did was to rethink the whole range of lever harps for two main reasons. First, we had too many models. Even our staff couldn’t tell the difference between some of the models. There were many models with the same number of strings and the same materials, but different shapes. So we wanted to make a clearer range of harps. Second, was the challenge of figuring out how to make harps more efficiently. We needed to make the same number of harps with 10 percent less time. That was only possible by redesigning the models to make the production more efficient. So I redesigned the entire line of lever harps in the early 2000s.

Then it was a process of redesigning the existing pedal harp models. Most of our models existed before Joël passed away. We created the Élysée, which was one of our first new models. This was an homage to Erard. I was lucky to have in our collection an original Empire model Erard with bronze ornaments. We completely dismantled that harp and created molds from those original parts to create the Élysée as a modern version of the original Erard from the 19th century.

EP: We made the Vendôme at the same time. Before that there was really nothing in that range between the beginning harps and the concert grand.

JF: So my main design work was on the sound, as I mentioned before. I’ve been working for 14 years on redesigning the structure of the sound box, mainly taking the inspiration from Erard harps. I’ve been rediscovering how they made the harps and using the modern tools of 3D design and modern machinery to build modern harps with the same concept of shapes they would have used in the 19th century. This was how we achieved our new sound, which is so successful today. To introduce this new sound, we had to create a new model. That’s when Eric really made a difference on the marketing side to find a good way to introduce this new sound with new models.

EP: There were some great improvements in terms of sound. But when you just use the models you already have, and you say to people, “You will see we have a new acoustic—it is great, you will be amazed,” and so on, sometimes people’s expectations aren’t met. When they play it, they might say “It’s not too bad, but it’s not that great either.” For many years Jakez had wanted to make a marquetry harp and a harp in tribute to the Art Nouveau style. We decided this was a good opportunity to make these two new harps—the Canopée and the Art Nouveau. We really wanted these harps to break the mold of what people thought a Camac harp looks like. We really worked to change the design to make something very different. We also did it without any big logos. When we showed the new models during the World Congress in Hong Kong in 2017, most of the harpists who played the harps said, “Oh, it looks great, sounds great.” Then finally, when they look at the plate by the mechanism they say, “Oh, it’s a Camac, which is strange because it doesn’t really look like a Camac. A lot of harpists were surprised because everything was new—the design was new, the sound was new, everything was new. When we saw what a big success this new acoustic was, we decided to adapt this new acoustic to our other existing models, but without any kind of advertisement to the fact that we brought this new sound to the Prestige and the other models in the range. We let the people discover that the harp sounds really great, but we didn’t say anything about it. The best advertisement was the harpist who said “I play the Prestige or I play the Vendôme, and it sounds great, it’s really good.” But we didn’t say anything. People just discovered that something changed.

HC: So you changed the outside, but you let the inside speak for itself.

JF: That’s exactly the concept. The idea was to create very attractive harps, so that harpists would come to see them, because it’s impossible for a harpist to be in front of a harp and not play it. And then the sound speaks for itself. In terms of the design, I am not so bad at drawing, so I have done all the drawing myself. From the first lever harp I redesigned until now, I’ve done all of the design. But I cannot draw on computers, so I do everything by hand and then work with an engineer to make all the designs become a reality for the harps. For the design of the Canopée, I drew all the shapes of the harp, and a craftswoman did the marquetry for the harp. I didn’t really design the Art Nouveau either. The Jubilé is a harp I had in mind for a long time. I wanted to make a modern-looking harp, and I was thinking about Japanese origami. In fact, it was during the pandemic when we were working from home that I had a lot of time to draw. I remember in March of 2020 I started to draw the first sketches of the origami harp. It’s a harp that needs to have a 3D design because it’s not just about lines and shapes, it’s about volumes because of all the facets. It was very challenging. After a few weeks, I couldn’t get any further. I needed to get help from a professional designer. So I worked with a designer named Thomas Hourdain very closely to take my sketches and put them in 3D. It was the first time, in fact, that we have worked with a designer outside the company. We have always done everything completely in house—from my drawing and our engineers—until the Jubilé. So he had to understand the instrument to take into consideration our limitations and how we build the harp. The harp was completed only a few weeks before it was presented at the World Harp Congress in Cardiff. When I started to draw that harp, I knew that it would probably be the harp to celebrate our 50th anniversary, and so its name became obvious—the Jubilé.

HC: What have been your biggest challenges in the last 30 years? And what do you think will be your biggest challenges in the next 30 years?

JF: Like I mentioned earlier, I think the biggest challenge was to continue after Joël’s passing. I was thinking of that just last night, about those rumors after his passing that some people would give us six months before we closed.

EP: That was 23 years ago, and we did not have the number of fans we do today. I had just come to Camac from another world, and it was a very scary time because when I was trying to sell harps, people said, “I don’t know if I can trust in Camac. Who knows whether they will be here next year.” So we are happy to still be here.

JF: The challenge for the next 30 years is to still be here and still be successful in 30 years so we will be here to answer your interview questions. [Laughs] To be here, we must continue to develop and face the environmental challenges before us. Probably the challenge of the coming years is to be able to continue to maintain the quality of our instruments while keeping in mind the impact of our manufacturing. Of course, I haven’t even mentioned the quality of woods available, which is also a concern.

HC: One final question: If Joël could see Camac’s 50th anniversary and everything the company has become, what do you think he would say?

EP: Joël was somebody with a very great heart. He should be so proud of what it is now. He would have been very happy, I’m sure. •

Getting candid with Camac

HC: Favorite Camac harp model?

EP: I would say the Canopée.

JF: My favorite harp is always the next one, the one I am imagining.

HC: What is your hidden talent?

JF: Drawing or cooking.

EP: Tango dancing. [Jakez answered for Eric]

HC: What has been your favorite location you traveled to for a harp trip?

JF: North Korea was my most interesting and surprising trip.

EP: For me, it was Iran.

HC: What place have you not been for business that you would like to visit?

JF: I sold a harp in the Fiji Islands, and I always dream of going back to service it.

EP: I would love to go to Korea.

HC: If you weren’t making and selling harps at Camac, what would you want to do for a living?

EP: I think I would probably open a bar.

JF: I would be a harpist in Eric’s bar.

HC: What music is cued up to listen to in your car?

JF: Silence.

EP: All the modern tunes.

HC: Coffee or tea?

EP: Tea.

JF: Green tea. Tie Guan Yin (an Oolong tea) from China.

HC: Croissant or pain au chocolat?

JF: Pain au chocolat.

EP: Both.

HC: You each have to answer this for the other. What is something about the other person that we don’t know?

JF: Eric is an expert in leathers.

EP: It was my old job [before coming to Camac]. I had been working for Hermes for more than 10 years buying leather.

JF: And the stories he has to tell about it are fascinating.

EP: Jakez is a great fan of Japan and loves the bonsai.