- burnishing the 23+ karat gold on a Prince William column

- Gluing down the top strips of a soundboard

- Two feet before and after hand-carving.

- Hand carving a Style 23 column.

- Fitting the neck action slot of a Style 85 CG column.

- A balmy 90 degrees in the drying room.

- Planing the rosewood inlay on a Style 23 Gold harp.

Lyon & Healy found a recipe for success early on, and 150 years later, they are still building harps from the ground up in Chicago.

When you pull up to the corner of Lake and Ogden in the old meat-packing district of Chicago, looking for a renowned harp factory, you might think you’ve taken a wrong turn somewhere. This gritty West Loop neighborhood seems an unlikely home to the artistic operations of Lyon & Healy. But there it is, a five-story brick building, standing eye-to-eye with the green line of the “El” (Chicago’s elevated rail system), as the train thunders by every few minutes. It is here where world-class instruments have been produced for decades.

The dichotomy of the rough physical exterior of Lyon & Healy’s Chicago factory and the beautiful instruments produced inside its four walls is not lost on anyone who visits. As with any space where art is created, the sense that something special happens here is palpable, from the sun-drenched corner of the second floor where a worker planes the edge of a soundbox by hand, to the small room on the fourth floor where 23-karat gold is painstakingly applied to the column of a Prince William.

Longevity

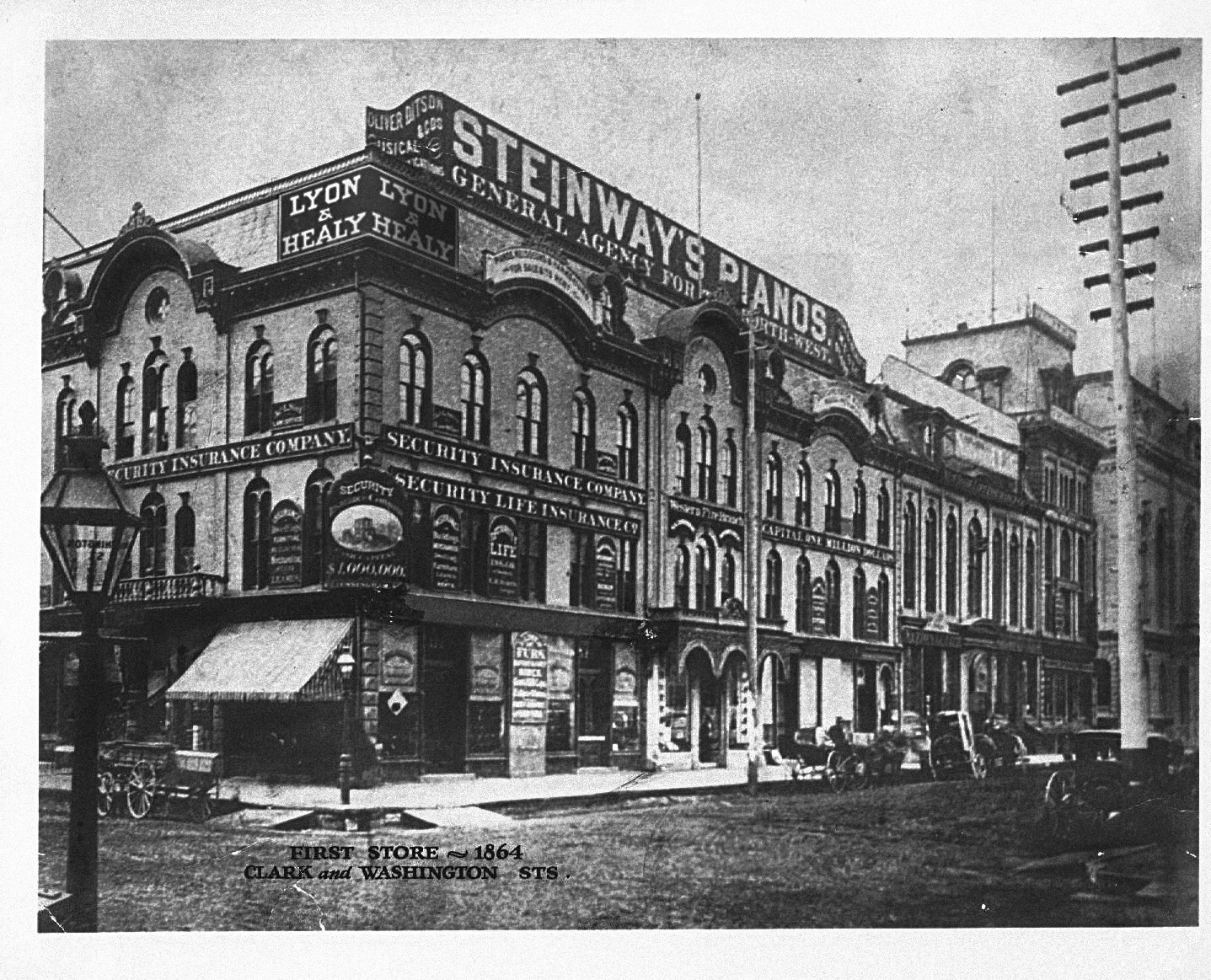

Lyon & Healy has been making harps on this site in Chicago since 1890. The company has been in its current building since 1928 and occupied an adjacent building for 38 years prior to that. George W. Lyon and Patrick J. Healy opened a small sheet-music shop in 1864 at the corner of Washington and Clark Streets, not far from Lyon & Healy’s current location. The company quickly expanded their business to making and repairing musical instruments. They survived two major fires, the second of which was the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. After 25 years in the instrument business, Lyon & Healy produced its first pedal harp in 1889.

Not many American companies have been around for 150 years. So what accounts for Lyon & Healy’s staying power? Well, many factors, of course, but perhaps it has something to do with Healy’s original intent when he set out to build harps. “Let us build a harp that will no longer worry its owner because of its liability to get out of order easily; let us build a harp that will go around the world without loosening a screw.”

The harps have staying power. The company’s first harp, a Model 21, #501, built in 1889, was still being used by a Chicago public high school orchestra until 1979. The resilience of their instruments has been a key to the company’s longevity. Lyon & Healy has survived a century and a half of economic ups and downs, devastating fires, even ownership changes, and nevertheless remains one of the top harp makers in the world today.

From the Ground Up

In the early 2000s, shortly after current Lyon & Healy president Antonio Forero arrived at the company, there were conversations about moving the factory to the suburbs. Operating a modern production facility in an old five-story building in the city has its challenges. But a move would have taken them away from what Forero says is one of Lyon & Healy’s secrets to success—the hands who make the harps. The 135 employees who build Lyon & Healy harps are uniquely skilled. “You can’t just run an ad and find these people,” Forero points out. The company’s apprenticeship program trains new workers under the more experienced workers. When there is a job opening, it is usually filled by word-of-mouth from current employees. This network of skilled craftsmen and women was too valuable to risk losing by taking operations out of Chicago.

So Lyon & Healy overhauled its building in the mid-2000s, putting in a showroom and concert hall on its top floor, while keeping its production facilities on the first four floors.

Tradition and technology

At Lyon & Healy, a harp’s life begins on the first floor and works its way up to its ultimate destination in the fifth floor showroom. In the first floor workshop, all of the mechanisms are assembled. Each mechanism works its way through four or five people who assemble and adjust it by hand. The mechanism is one part of harp building that has been aided by technology at Lyon & Healy. Machines and lasers do much of the metal cutting before it is finished by hand. Lyon & Healy also uses computer modeling to try out design changes before putting them into action on an instrument.

Body Building

Open the door to the second floor, and the sweet smell of wood wafts over you. At one end of the floor, a worker is using wood clamps to put a sound box together. They have been doing it the exact same way for more than 100 years, says Forero. “Early on, they arrived at a recipe for the unique sound of Lyon & Healy,” he says.

There are no straight lines on a harp, so every piece of wood is shaped by hand. It’s physical, time-consuming work. The Sitka spruce and bird’s eye maple arrive at the Chicago factory from the Pacific Northwest, northern Midwest United States, and Central Canada, and the rough timber looks nothing like its former self by the time it leaves the factory as a harp.

The Harp Makers

“This is where the harp makers are,” says Forero as we walk into the third-floor workshop where Lyon & Healy’s master harp makers take the parts that come up from the first two floors and create instruments. The wood carvers painstakingly sculpt the intricate column designs, breathing life into roughed-out designs. The wood also ages on this floor. For anywhere from six to 12 months, the wood used for the sounding boards rests in a temperature-controlled drying room—it’s a nice spot to hang out on a blustery Chicago day.

Coming Together

As a harp is being built, it moves from floor to floor on a cart. The pieces of each instrument are like a puzzle, fitting together uniquely. You can’t play mix-and-match with these instruments, because a fraction of an inch matters. The parts of a harp are varnished here—enough to protect the wood, but not too much so as to inhibit the harp’s vibration and resonance. That constant give-and-take between durability and artistry seems to be a common theme at each stage of Lyon & Healy’s harp building process. The harps start to take a recognizable form here, gaining the pedals and strings.

Tucked into the far corner of the fourth floor is the gold room. Here, workers carefully apply 23+ karat gold leaf to the harps the same way they did 100 years ago. In fact, gold harps used to be the norm, not the exception. Until the Salzedo model came out in 1928, every harp Lyon & Healy made was gilded with gold—even the student models. The process of applying gold to a harp is long and tedious—it can take three to four months to apply the gold to a Louis XV—so it is easy to see why the gold harps occupy the top of the price list.

Show Time

By the time a harp makes it to the fifth floor showroom, it has been winding it’s way through the factory for up to a year. The forest of harps that greet prospective buyers when they walk into the fifth floor showroom would make even the most seasoned harpist light up.

On this day, a teenage girl was deliberating over a few different models in the Grandjany Room (the showroom has private practice rooms named after famous harpists), while her parents sipped coffee and listened. Meanwhile, other harpists browsed the rows of new harps, trying to decide which one to try next. Harpists come here from all over the world to pick out their instruments. Forero said that one day two harpists from St. Petersburg, Russia, showed up at Lyon & Healy’s doorstep, without warning, to buy a harp. Luckily, the pair found what they were looking for, otherwise it would have been a very expensive sight-seeing trip.

Each harp that leaves the factory will find a new home—a living room in Minnesota, a university in Beijing, a concert hall in New York. But they all started at the same place—the corner of Lake and Ogden in Chicago. •