If you have played harp music for any length of time, you’ve likely encountered a piece or two where something sounds off or looks odd to you. Could that be a wrong note in your part? Is the score missing a sign? Is that rhythm printed correctly? Mistakes can find their way into a printed score for many reasons, so it’s important to be able to spot them and correct them when you have a hunch something is not right. Mistakes in printed music are so common that books have been written and conferences have been held on the topic. In this article, we’ll highlight various things to look out for when your ears and brain disagree with what’s on the page.

Errata or new edition

In a 2020 session titled Proofreading and Errata: Mitigating Mistakes, the Major Orchestra Librarians’ Association (MOLA) defines “errata” as not only wrong notes, but bad page turns, poor fonts, or inappropriate clefs—anything that can hinder or stop a rehearsal. MOLA also points out the problem of so-called “Frankenstein sets” of mismatched scores and parts, containing changes within the editions. In these Frankenstein sets, some, but not all, parts have been corrected and published under the same catalogue number.

Sometimes there are variations among different editions of the same piece where the composer made revisions after the first edition was published. The most well-known example might be Beethoven’s overture to Fidelio, which went through at least three revisions. Wagner’s overture to The Flying Dutchman has two different editions of the harp part. There are multiple versions of ballet harp parts, since they are often based on the specific ballet company’s orchestrations, or the harpist has been given free rein to alter cadenzas. The Firebird by Stravinsky has three completely different suites. Be aware of the edition you are playing—what you suspect is a mistake in the part could simply be an outdated edition.

When the original is wrong

Harp music editor Carl Swanson has worked with many hand-written manuscripts, which he says often contain errors. “When comparing the published work with the original manuscript, there can be lots of mistakes. Many musicians want a publication that is simply an exact copy of the original manuscript. Oh my, if they only knew what they were asking,” he says. “I can think of several mistakes that Debussy made in the manuscript of his Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp: forgetting to put a key change in the middle of the third movement, forgetting to put 8va over several measures at the end of the first movement, writing a unison line for the viola and flute in the first movement, and momentarily forgetting that the viola line was in the C clef, and writing one viola note one step above the note it should have been.”

Swanson says he frequently encounters confusing markings in an original hand-written manuscript that he must edit out. “Often the composer puts in unnecessary accidentals: the same G-sharp appearing three times in one measure, a piece in the key of F with a key change to G in the middle of the piece, and three measures after the key change, a natural sign in front of a B. Accents appear on the melody notes in the first two measures, then the melody continues and there are no accents. Do I continue the accents to continue the pattern? Or do I simply copy the music exactly as it is written?” There are questions music editors wrestle with before their edition goes to press.

Swanson points out that many errors make their way into a piece because of a composer’s priorities and process. “Composers, in writing out the composition the first time, are not thinking in terms of how the player is actually going to play the piece. They are totally consumed at this point with just getting the composition down on paper,” he says. “[Marcel] Tournier is notorious for this type of thing. He has double flats and double sharps all over the place, and that’s very confusing for harpists. He writes grand arpeggios that cover both staves without indicating which hand is playing what. He will write a four-note chord for the right hand, with two of the notes in the lower staff and two in the upper staff, when the whole chord could easily be written entirely in the upper staff. He will have notes written in, but frequently doesn’t fill out the measure with the necessary rests.”

Swanson says that Tournier included a very telling footnote in his piece Fresque Marine. An asterisk at the beginning of one of the measures indicates, “These measures are written the way the harpist needs to play them, and not musically correct, as they should be.” Swanson adds, “Much of my editing has to do with showing the music the way it is going to be played. With all my editions, I never simply pull out my personal marked up copy and use that. I always start with a clean copy of the piece and figure out the best way to show how it is actually played. I ask several first-rate harpists to send me copies of their marked editions so I can compare what I have done with what other good harpists have done with problematic passages. Each time, the markings are virtually the same from one harpist to another. I recently worked on the Hindemith Sonata, and I asked Kathleen Bride if she would send me copies of Grandjany’s marked copy. She did, and at least two-thirds of his markings I already had down in the version I was working on.”

But we’ve always played it this way

Sometimes an error in a part has flown under the radar for years, maybe even generations. How do misprints occur in music that has been in publication for a long time? “No person or notational software program is infallible,” says harpist Lynne Aspnes, professor emeritus at the University of Michigan. “Transference can be an issue, and though diligent proofreading is the gold standard for the profession, there is also the slim chance that a change to the printed score in different editions is made intentionally. It was not unheard of for the maps printed in a travel atlas to contain intentional errors: towns left off, names reversed in order to circumvent copyright laws. Those types of situations aside, creatives often change their minds after a first publication, be that a piece of music, a book, or even a painting, and make alterations to the original. Often performers, working with composers after a work is first published, will suggest edits that then make it into later publications, but are not reflected in the original publication.”

Even with meticulous copying with good software or typesetting, mistakes can happen if the original manuscript is hard to read. The copyist can miss something if they are tired or distracted. Illegible calligraphy in a hand-copied piece can result in such things as wrong numbers of beats in a bar, inscrutably placed or missing accidentals, bad spatial placing of notes, dots, or ledger lines. Perhaps a squashed bug, an ink blot, or a spilled drink could be the culprit! Badly aligned notes between the staves or in chords are rife in hand-written music, which, thankfully, is much rarer in software-transcribed pieces. Sometimes the beaming is incorrect in typeset or hand-written music; I’ve seen 32nd notes beamed as 16ths, or the reverse. Glissando pedal diagrams or note indications can be wrong. The beginning of Afternoon of a Faun by Debussy used to have the wrong pedal indications with A-sharp and A-natural in the same set of instructions. This would require eight pedals! Not exactly misprints, but unwieldy or untraditional music notation can cause mis-readings, such as writing 8va on top of a bass line instead of simply changing the clef to treble. Errors can occur when copying and pasting; sometimes there are a few changes that have been missed.

There are numerous types of errata: wrong notes, rests, bars of rest, dots, accents, dynamic markings, misaligned chords, misspellings of titles or instructions, clefs, 8va, wrong pedal diagrams, missing pedal changes, missing accidentals, misplaced rehearsal letters, incorrect cues, you name it! I actually had a Richard Strauss part with “bisbigliando” spelled “bispigliando.” In some music, the pedals are correct but the note is misspelled (e.g. F-sharp/G-flat), or only some of the pedal markings are included.

Our expectations will sometimes cause our brains to override what we’re looking at. Many of us will not notice a missing clef or accidental, and we play the passage correctly, not even seeing the written mistake. I did not notice the missing clef in the solo cadenza in Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G Major until one of my students played it for me exactly as written! In Naderman’s “Etude #10” from his Douze Etudes for Celtic Harp, the third bar has an F that should be a D, which I played correctly until a student played it as written.

How to spot a mistake

We often assume what is printed on the page is correct, so how do you spot a mistake? “For me it always starts with my ears,” says Aspnes. “Harmonic consistency is next, and then how the notes feel under my hands. Music is, in the end, more patterned than random in its composition. When I hear, or feel, a departure in a repeated section of music, that catches my attention.”

Whether you are playing a solo or in a group, you can sniff out these mistakes. Does the harmony sound wrong or inappropriate for the style or time period? Are the rhythms not syncing up to the rest of the ensemble? In an orchestral or chamber music part, is the harp the only one playing a note that does not go with anyone else’s harmony? Here’s where it gets tricky—any of these things can be true, however, it may still be correct! In Stravinsky’s orchestra piece Scherzo à la Russe, rehearsal numbers 10–14, the piano and harp parts are one note apart, and it sounds wrong. A similar head-hurting passage is in Bernstein’s opera Candide, in the aria “Glitter and Be Gay.” I assumed that I had miscounted, then adjusted to play together with the other instrument, only to find that it was supposed to be out of whack.

If there is a recapitulation or repeated passage in which only one note is different from all the rest, it is possibly a mistake. If there are two or more slight alterations, the composer might have been trying to alleviate boredom—theirs or the audience’s! If the measure or rehearsal numbers are missing or misplaced, the mistake will be clear when everyone starts in a different place than you do. A mistake might be simply the binding of a piece, where one page is missing, or the pages are out of order. Volume 2 of Annie Louise David’s Album of Solo Pieces for the Harp (1916) is missing a whole page of “The Brook” by Hasselmans in between page 22 and 23. Yes, I am writing this from a traumatized experience.

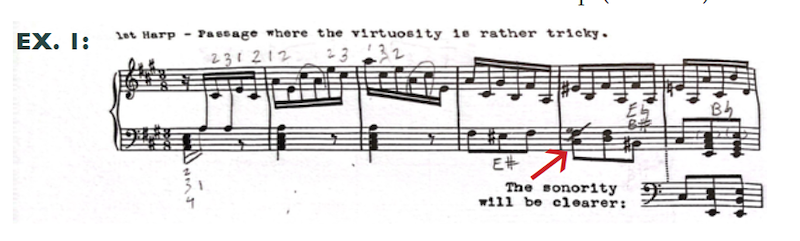

Arrangements can often contain wrong harmonies or voicings. If you have access to a recording or score of the original piece, take note if something seems off. If you own a method book, excerpt book, or collection, there is a good chance that there will be some mistakes. This example from Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique is from Henriette Renié’s method book, in which the F-sharp in the fifth measure should be a G-sharp. (See Ex. 1)

What to do when you find a mistake

It’s really a question of when, not if, you will encounter a potential mistake in your music. So what is a conscientious harpist to do when they think they’ve spotted an error? Many times fellow harpists are your best first line of feedback. You can ask harp friends, colleagues, and harp groups on social media.

What do you do when facing a piece that has been performed wrong so many times that the correction sounds like the mistake? An explanation in the program notes might solve the problem. If the composer has written inconsistent accents or arpeggiation indications, then you need to know the style of the time period and try to extrapolate the intent. For example, if you know that a piece was written in a period where it was expected to roll all chords whether marked or not, then the composer did not need to indicate that.

When investigating an error, Aspnes says her first move is to consult the original source material wherever possible. “Start with either listening to a recording of the composer performing the piece, or get your hands on more than one edition of the piece you are playing. If you cannot hear or see the composer’s first iteration, get as close to their work as you can. Find a harpist who studied with or worked with, the composer. Barring that, research written material from the time the work was premiered,” she says. “As much as possible avoid anecdotal information and edited versions of the piece you are playing, unless the ensemble or competition has specified an edition.”

Aspnes says harpists have to put on their detective hats to crack these musical mysteries. “Contacting publishers is always an option,” she says. “You can also consult printed resources, which in North America would include the archives of The American Harp Journal, the International Harp Archives at the Harold B. Lee Library of Brigham Young University, the American Harp Society Repository held at the Library of Congress, the Canadian Music Centre, and composer collections in the Juilliard library and the Sibley Library at the Eastman School of Music.”

If you are in an orchestra, report the mistake to the music librarian and the conductor. Every orchestra librarian has access to MOLA’s errata and can check for you. Don’t shrug it off and let the next harpist deal with the same issues. The librarian will correct the part so that another orchestra’s rehearsal time is not wasted. If you encounter a mistake in a part sent by an orchestra for an audition, ask their personnel manager to check it out for you.

Some years ago on the Harp Column website forums (harpcolumn.com/harp-forums), I became acquainted with Clinton Nieweg who was the principal librarian of The Philadelphia Orchestra. He has issued many corrected editions of previously error-ridden orchestra parts. I ended up collaborating with Nieweg on some editions. Some of the mistakes I refer to in this article may have been subsequently corrected. I asked him to share a little bit about his experience with errors in orchestral parts.

“When I was principal librarian at The Philadelphia Orchestra, Nancy Bradburd and I proofread the score and parts of each new work before it was added to the rehearsal folder. We tried to have the parts ready seven weeks in advance. This was at the request of [music director] Riccardo Muti.

“I budgeted funds for the library to buy facsimiles of the score or first editions. These were valuable to use as sources. This proofreading process saved the orchestra hours of time in rehearsal. Musicians and conductors would bring questions to the library so that we could consult the sources. Any member of the orchestra was encouraged to report or question the notation in their part,” Nieweg explained.

Now that we have access to an online library of scores and parts called IMSLP (International Music Score Library Project found at imslp.org), it is very easy to check the score if it is in the public domain. However, in some cases, even the score has mistakes! Then more research needs to be done.

If the composer is still alive and kicking, connect with them. Sometimes a misprint has not been noticed even after the music has been published for a while. All the composers who I have spoken with were very grateful, though horrified, to have the mistake discovered.

Reliable sources

In 2007, I began researching the Leduc publication of the Ibert Entr’acte for flute and harp or guitar. It is based on a flamenco scale. In one place, the scale suddenly has a B-natural that does not appear anywhere else in the piece and is jarringly wrong to my ears. Everywhere else in the piece, it is a B-flat. There was also a missing bar in an earlier edition. In the guitar version, there is no B-natural courtesy accidental marked, but no B-flat either. Possibly an omission? I corresponded with Alexandra Laederich and Agnès Klingenberg of the Nadia and Lili Boulanger Foundation, but the issue could not be resolved because the manuscript had been lost. This remains a mystery for now.

I corresponded with Peter Bartók through Nieweg about an incorrect clef in bar 171 of the first movement of Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. It was marked as treble clef, but should have been in bass clef. He responded, “Since my father wrote the glissando with a bass clef, I see no reason to have changed it to a treble clef. We are trying to find out why the publisher made the change. Thank you for bringing this to our attention. Sincerely, Peter Bartok, 22 January 2007.”

In a section of Leonard Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances, my part was supposed to happen at the same time as the xylophone, but it was in the wrong place. The written rests were wrong not only in the part, but in the score. I knew it was incorrect as printed, but the conductor was unconvinced, so I had to reference a recording by Bernstein to prove my point. Back in 2006, harpist Serena O’Meara posted on the Harp Column forums that her conductor confirmed the mistake, writing, “Actually, the mistake is in bar 615—Vibraphone and harp play the same rhythm. It should be a quarter rest on the first beat, followed by a dotted eighth rest, then the rhythm passage, a quarter rest on the fourth beat. Bar 616 is correct—it has a dotted eighth rest followed by the rhythm passage, then a half rest. The score has the same mistake in bar 615. So, bar 615 and 616 are different. I have two CDs conducted by Bernstein, another by Michael Tilson Thomas, also I have even a video of Bernstein conducting this piece—all performances and recordings I have listened to play the way I described.” Another harpist, Julie Alberton, followed up on the forums, adding, “Here’s where I think the mix-up may be: in the older manuscript/handwritten parts, these bars are correct (or had been previously corrected in my copy), but in the newer typeset parts, there is the mistake in measure 615. It is wrong in the harp part, vibraphone part, and the conductor’s score. So, no matter what version of the part you have, be sure that measure 615 is a quarter rest followed by a dotted eighth note rest, then the musical figure followed by a quarter rest. 616 is correct in both versions: dotted eighth rest, musical figure.”

Learning by example

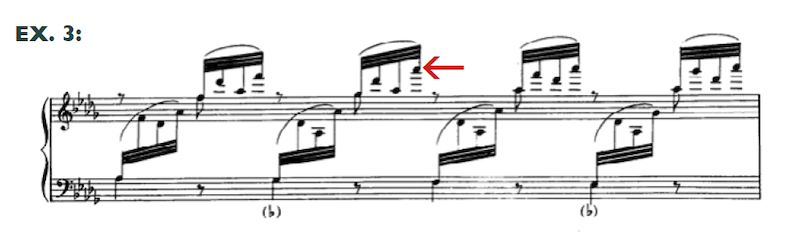

Because there can be so many different ways errors can appear in music, it’s helpful to see examples of where mistakes have been identified. Studying these examples can help you calibrate your mistake meter when looking at your music. Retired Toronto Symphony harpist and longtime pedagogue Judy Loman gave several examples of mistakes she has identified in the standard harp repertoire.

In Maurice Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro at rehearsal #22, in the third bar, there should be a G-flat, moving to a G-natural in the fourth bar. (See Ex. 2)

In the first movement of Germaine Tailleferre’s Sonata for Harp, measure 11 should look like measure 13. “They are the same, but bar 11 is notated in a way that makes one play the wrong rhythm,” Loman points out.

In Gabriel Fauré’s Impromptu, Loman says, “I firmly believe that the fourth 32nd note of the fourth group of 32nd notes in the 12th bar from the end should read as G-flat, not A-flat [as written], following the line taken in the previous groups of 32nd notes.” (See Ex. 3)

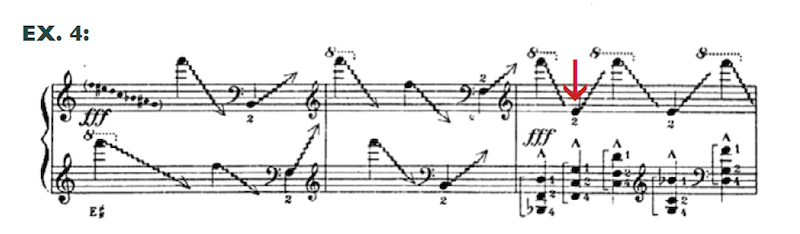

In“Whirlwind” by Carlos Salzedo, measure 10 on page two, the fourth glissando in the right hand should begin with a third octave C–natural, not the fourth octave E that cuts off the top of the left-hand chord. “This is the only place in which the melody line is cut off by a note beginning underneath it,” she notes. (See Ex. 4)

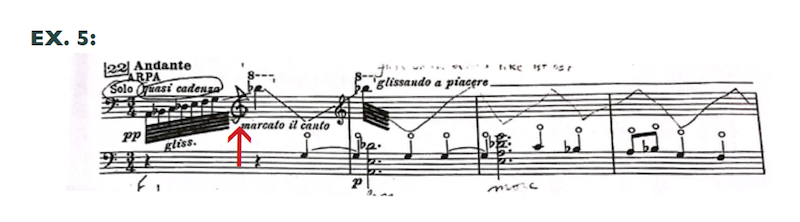

I’ve also found a number of mistakes in the standard harp rep. In Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G Major, a treble clef was misplaced in the cadenza in the first movement at rehearsal 22. (See Ex. 5) It should be before the top note of the glissando on the second beat of the bar. (See where it is written in by hand in Ex. 5)

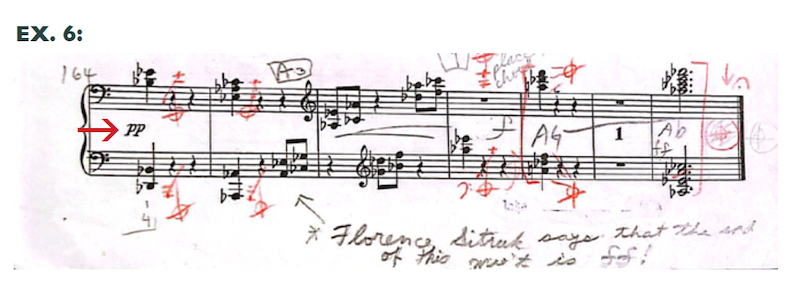

The end of the second movement of Paul Hindemith’s Sonata has an incorrect dynamic marking. Harpist Florence Sitruk, professor of harp at the Haute Ecole de Musique of Geneva, Switzerland, gave an excellent presentation on this sonata at the World Harp Congress in 2011. In my copy (Schott edition), the only dynamic marking before the end was a pianissimo in measure 164. Sitruk said that the end of this movement crescendos to a fortissimo on the last chord. (See Ex. 6) That is quite a difference!

In Escales by Ibert, my harp part had many mistakes in the numbers of bars of rests. I kept missing my entrances and had to check the score with the conductor in the break. We were both relieved to find out that I was not an idiot, and I was not miscounting.

Scores of mistakes

Nieweg offered several harp-specific mistakes identified in the standard orchestral literature.

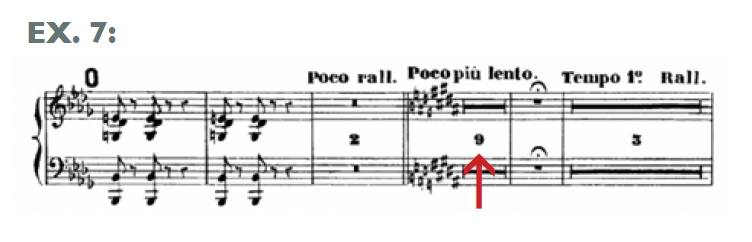

Symphony In D Minor by Cesar Franck, Hamelle first edition (1890) and uncorrected reprints: In movement 2, rehearsal O, measure 5, Poco Piu Lento, change nine measures of rest to three measures of rest. (See Ex. 7)

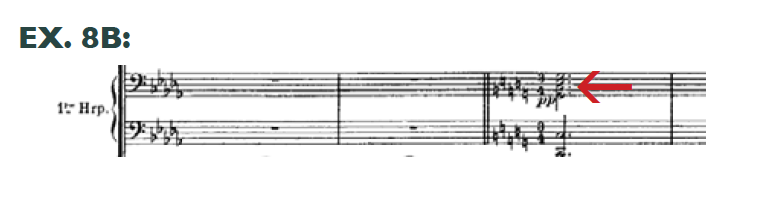

Daphnis et Chloé Ballet M57 by Maurice Ravel: Harp 1, Rehearsal 81, right hand, the B written should be a C-natural. The score has a C-major chord. Harp 2, both the piano dynamics before rehearsal 81 are not in the score and are redundant. See the incorrect harp notation in Ex. 8a and the corrected notation for Harp 1 in Ex. 8b.

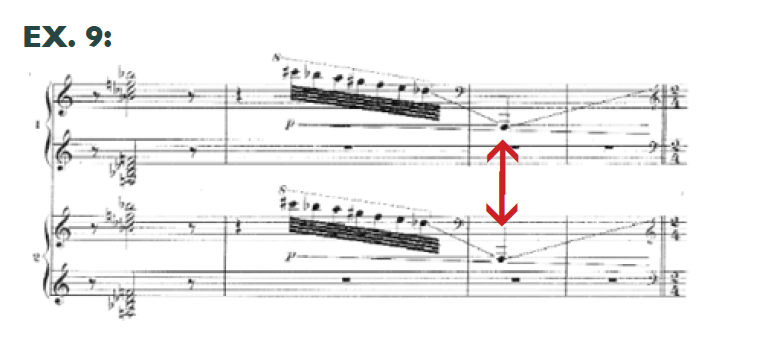

Daphnis et Chloé Ballet M57 and Suite II M57b by Maurice Ravel. Harp 1 and 2: rehearsal 220, measure 6. Clarify with a (quarter rest) on beat 1 that the glissando ends and starts up again on beat 2. (See Ex. 9)

Focusing only on mistakes in harp parts, the number of mistakes that appear in our music, while large, seems manageable with careful attention to detail. But when you consider the harp as one instrument in an orchestra of 80 or 100 musicians, the scale of the problem quickly becomes overwhelming. Nieweg shares these numbers to put the job of an orchestral librarian into context:

Rite of Spring K 15 by Igor Stravinsky (Nieweg/Chang, 2021 edition. Pub. Serenissima Music Inc). This edition has incorporated 2,200 edits and corrections, building upon the Nieweg 2000 edition which itself had incorporated 21,000 edits and corrections. These 23,200 corrections were made to the Boosey rental material. The source for the corrections was a facsimile of the manuscript corrected by Stravinsky in 1920.

La Mer L109 by Claude Debussy (Nieweg/ Bradburd—Serenissima Music Inc.) There were 7,000 engraving mistakes corrected from the Durand 1905 publication for the 1909 version reprint.

Firebird Suite 1919 K10 by Igor Stravinsky (3rd printing Nieweg/Westfall—Serenissima Music Inc.). This edition includes over 5,000 corrections compared to the Schott/Chester original publication.

Trust your instincts

So the next time a jarring chord or awkward rhythm causes your ears to perk up, follow your instinct. Harmonies and voicings are obvious in Bach and Mozart, but get hazier as we progress into the crunchy, chewy music that arose later. Be a sleuth—consult original sources, investigate recordings and scores. Just as in other parts of life, don’t believe everything you read and rely on reputable sources for your information.

Many thanks to Carl Swanson, Lynne Aspnes, Clinton Nieweg, and Judy Loman for their help with this article. •