10/10

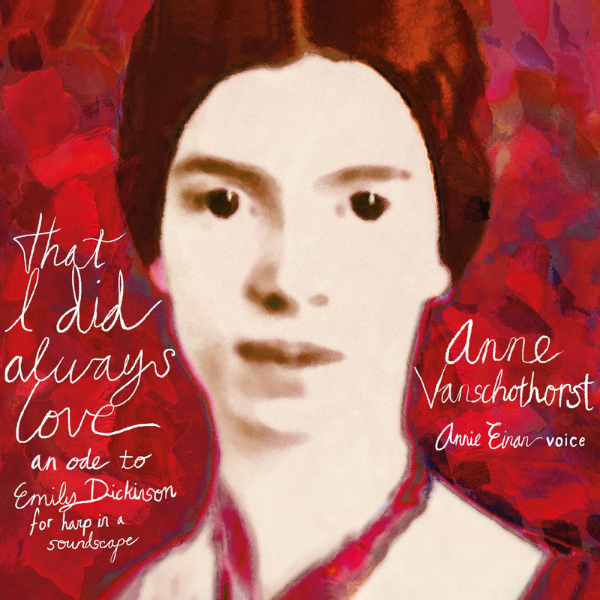

Anne Vanschothorst, harp; Annie Einan, voice.

Big Round Records, 2024.

In a captivating new recording That I Did Always Love,Dutchharpist Anne Vanschothorst distills the essence and beguiling nature of one of America’s greatest and most original poets of all time, Emily Dickinson.

Her ode of eleven original works is cinematic yet lyrical, minimalist yet pregnant, and expresses precisely what is needed to be expressed. More than simply an accompaniment to Dickinson’s words read aloud, there is a synthesis of art forms, a partnership that speaks to the genre-breaking style of this 19th century iconoclast who was able to make the abstract tangible and create meaning without confining it.

Vanschothorst’s passion for Dickinson stems from her own aural landscape-architect sensibility. “My passion, desire, restlessness, insecurity, despair (life is really felt in absence),” she explains, “are filtered in the serenity of my harp talk. Heart/soul, time, space, and silence are essential (without silence there is no music!), so one can escape into the music, another reality, an alternative beautiful (dream) world, and might have fun whilst unraveling the mystery of life or finding fudge.”

You may not fudge on this singular journey (!) but you will certainly enter a new world of beauty from harp, ambient sound, and voice, but not before Vanschothorst stakes her claim to her creative world with A harp note to Emily Dickinson. Here she sets the mood of reverie amidst intermittent scratching of a pen and the sound of boiling pots, presumably to alert us that something is cooking, an entirely new way of seeing the world. Birds enter eventually, nature always a theme for Dickinson whether actual or metaphorical.

Dickinson wrote using a style not familiar in her time utilizing short lines plus slant rhyme. That’s when a poet uses words containing similar but not exact sounds. Vanschothorst, too, responds musically in unexpected ways, leaning into pauses and dramatic timing. Take this stanza:

The Soul selects her own Society —

Then — shuts the Door —

To her divine Majority —

Present no more —

Vanschothorst reflects on these words and their meaning for a modern audience, particularly when it comes to women. Using a bow and drumstick plus alternative plucking techniques, the resulting soundscape underscores a chant by a crowd of Iranians protesting recent injustices with a chant, “Women, Life, Freedom.”

A favorite of mine in this eclectic collection is Trees of mercy, a stunning collaboration with the “Talking Trees” orchestra born of a world-wide collaboration between artists, scientists, and others to share their connections to nature. Snow melt and streaming water make their way into this beguiling work as well as as rhythm based on the movement of sap in an oak tree. Would it matter to your listening if you did not know this fact? Perhaps. Nonetheless, there is magic in the ambient, found-sound quality of the collaboration.

Dickinson’s speakers are often sharp-eyed observers who understood what it meant to be trapped in their society, but could somehow see a route to their own liberation. Her style leaves the reader (or listener in this case) slightly unsettled in ambiguity and unrealized potential. Not to say that Vanschothorst’s music is challenging, but one should enter her space willing to go on a journey that is far more than solace or tranquility.

That’s a delicate balance which Vanschothorst lands precisely, never overly sentimental or maudlin, giving us food for our mind, heart, and soul.