Download this issue to get this tune now!

In this issue we are kicking off our newest article series—Tear-Out Tunes. Over the course of the next year, we will feature six new works in this space from some of the best harpist-composer-arrangers in the business. Each composer will tell you a little bit about their piece, and also give you some helpful tips for learning it and getting the most out of the experience. The new piece is yours to keep. We even put it right in the middle of our print issue so you can tear it out and put it on your music stand. Our first installment of Tear-Out Tunes is by harp pedagogue Anne Sullivan. She has written an etude playable on pedal or lever harp, which can also be used for Harp Column’s annual 30 Day Practice Challenge that begins on Jan. 1, 2023. Sign up for free here. We hope you enjoy it!

If you’re going to spend time learning an etude, you should at least know why. It’s not just about getting your fingers to play the notes.

Etudes create a bridge between bare-bones drills and exercises and our repertoire pieces. They provide a musical setting, albeit a rather narrow one, in which to test a fundamental skill such as scales or arpeggios. You could think of basic exercises like an old-fashioned spelling test and etudes like a vocabulary test. Being able to get your fingers around a pattern is comparable to being able to spell a word; playing that pattern in a musical context is more like learning the meaning of the word and using it in a sentence.

To maximize the value of etude practice, you need to do more than learn the notes and play them securely. You need to understand the musical application of the skill in that particular etude. In fact, there may be more than one. What are the considerations beyond technical precision that the etude requires? Does the etude test your skill with varying dynamics or articulation? Is it about legato? Is it all about the tempo, or maybe about your tone? The musical considerations of an etude are the testing ground for your technique.

Of course, etudes also help develop what one of my students and I call “finger smarts”—the ability of your fingers to respond automatically and with accuracy to a variety of circumstances. In other words, etudes help train your fingers to be “smart” on their own, with as little conscious direction from you as possible. This is what makes for speedy learning and fluid sight-reading and also helps you recover from missed finger placings in performance.

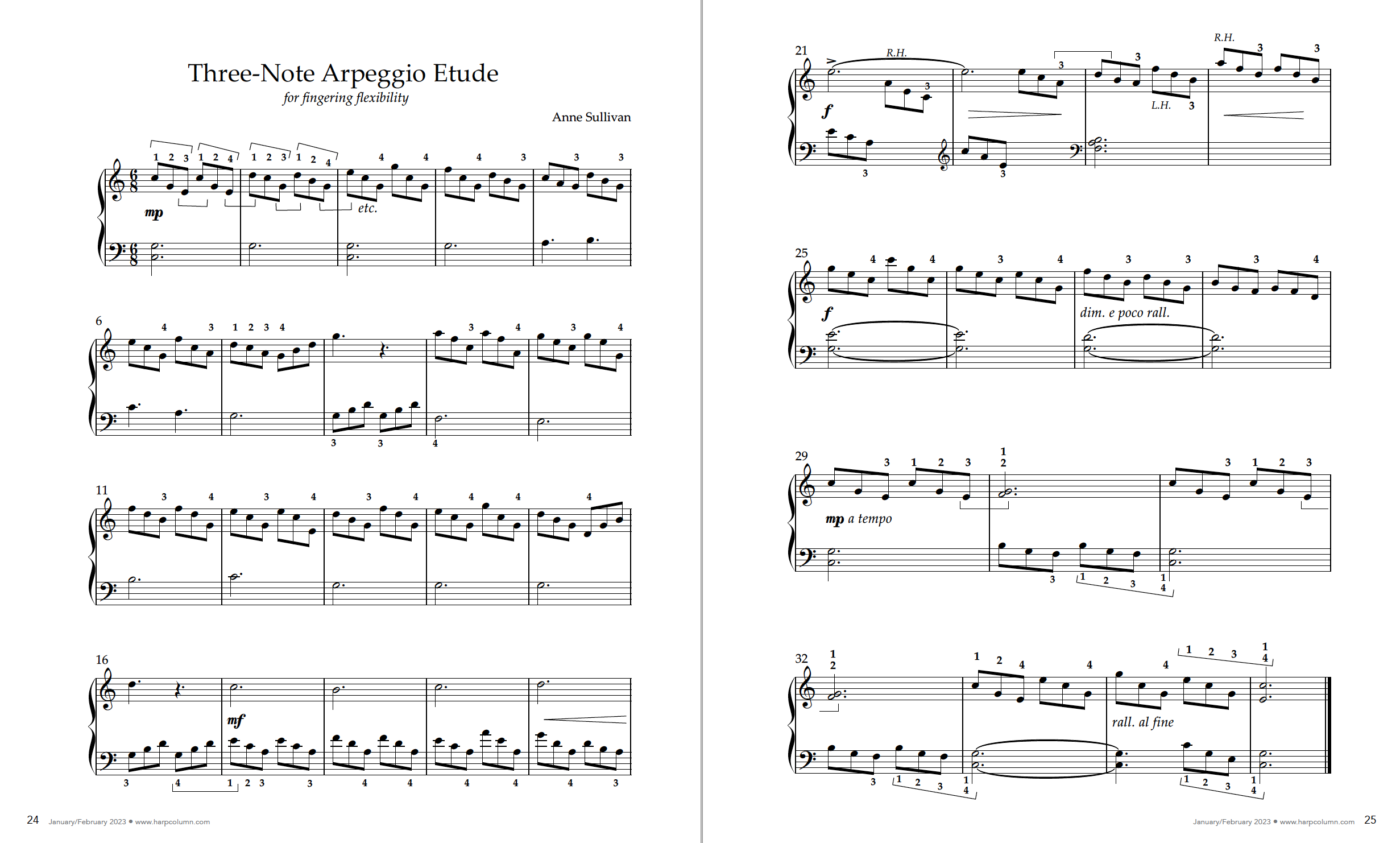

The music on the following pages is a three-note arpeggio etude designed to be a study in fingering flexibility, meaning the flexibility to use different finger combinations in sequence and to switch smoothly between them. Downward arpeggios, particularly when they are connected in series, often require a harpist to make quick fingering switches and to use finger combinations or reaches that may be different from the ones normally practiced. For instance, while we may normally use the thumb and third finger for the reach of a sixth, a continuous arpeggio pattern may sound smoother if we use the thumb and fourth finger instead. Having the finger independence to adapt is key to quick sight reading and fluid execution.

One of the growth stages in harp study is moving from three-finger agility to four-finger agility. Every harpist recognizes that four-finger chords have a significantly higher difficulty factor than three-finger ones. Similarly, developing the same agility level in your fourth finger in scale and arpeggio passages is also required to move your technique to the next level.

The fingering printed in this etude reflects the changing finger patterns that will create that adaptability, switching between third and fourth finger. Sometimes the fingering will seem awkward, but that is the point—learning to play these unusual combinations and shapes will help build your fingers’ repertoire of responses.

You should adhere to strict placing too, placing both fingers before playing your thumb, to develop accuracy and security. Also, be sure to connect each group to ensure smooth placing and develop legato.

You will find, however, that you derive extra benefit by employing some variations. For example, while the printed fingering is beneficial, you could also finger all the arpeggios in the etude with thumb, second, and third fingers (1–2–3), or with thumb, third, and fourth fingers (1–3–4), or with thumb, second, and fourth fingers (1–2–4). This will help you develop even greater agility.

To test your new finger smarts, make a copy of the etude and Wite-Out the fingering. Can you still play it smoothly without worrying about your fingering choices? Can you alternate between the third and fourth fingers automatically, without stopping to think?

You could also change the placing protocol. Rather than placing the fingers both at once, try placing only one finger in advance. Placing just the next finger in the sequence can result in a more legato sound by allowing the strings to ring as long as possible before you replace and stop the sound. This is essentially an expressive choice, but it could help solve a technical issue too, by avoiding a finger buzz or replacing too soon on a string needed by the other hand.

There is no tempo indication for this etude in order to allow you to experiment with different musical ideas that may require different technical approaches. For instance, at an allegro or allegretto tempo, you may find it best to use precise placing to ensure secure, even notes. At an andante tempo, placing one finger at a time may produce a more legato flow.

If etudes are a bridge, where does this particular bridge lead to?

Descending three-note arpeggios are not difficult to find in harp music. Samuel O. Pratt’s beloved piece “The Little Fountain” is one example. Linda Wood’s “Processional” includes an entire variation of them. “Nataliana” by Deborah Henson-Conant employs these arpeggios as does the first movement of Sonatina No. 1 in C by Dussek from the classical repertoire. This etude will prepare you for those pieces and many more. •