Imagine that you’ve just been hired as principal harpist of an orchestra. Your first order of business should be to learn the most demanding parts that will frequently sit atop your music stand—tattered pages staring you in the eye. If you’re lucky, you’ll find out what these are and get the parts before the season starts. If you’re not so lucky, well, good luck.

Take it from the Pros

Find out what pros around the world think are the “must know” orchestra parts in this article extra.

Every orchestra has its favorite pieces that it programs time and time again. Some of these have harp parts that require a great deal of work to master, and there is rarely enough time in the schedule to put in the hours necessary, especially given the demands of the rest of your career and family life. Rather than panic and cram a major harp part under time pressure, most harpists try to learn these mainstays of the orchestral literature on their own time, long before they get that last-minute call to play Symphonie Fantastique this weekend.

Harpists also find many of these major parts on orchestra audition lists, which is another reason to learn them early, before you need to perform them. In some cases, the way you would perform these parts on the job is different from how you would play them in auditions. Audition panels are listening for certain things demonstrated in these excerpts, despite the pieces not being a part of the usual repertoire of that orchestra. They need to hear if the harpist has good rhythm, technique, accuracy, musicianship, good muffling, style, tone, harmonics, and solid pedal technique. They want to hear that the harpist knows the entire piece, not just the harp part. Sometimes a fairly simple piece will be on an audition—that is when they are listening for finesse and beauty, and quiet pedals!

Remember that, in practice, the orchestra may take speeds that are much faster than the marked tempi, and it is your job to sound smooth and seamless even when the notes have become impossible. In an audition, you are expected to play all the notes (unless otherwise marked in the parts sent by the orchestra), but not at breakneck speeds beyond the marked tempo. (See my article, “Mission Possible” from the May/June 2014 issue of Harp Column.)

We asked orchestral harpists around the world what was on their orchestra’s list of top ten harp parts. There are differences due to the contents of the orchestra’s library, the budget for renting unusual pieces, the conductors’ and audiences’ preferences, the number of musicians in the orchestra, and the management’s ability to take risks in their programming. Despite these differences, every orchestra does have its list of beloved, familiar repertoire; here is an (unscientific) look at the top ten harp parts among them.

1. Symphonie Fantastique

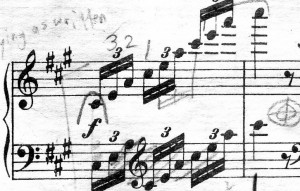

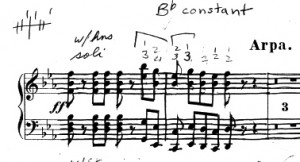

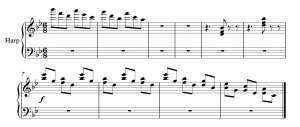

Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique has only one movement with a harp part, “Un Bal.” You have to sit through the first movement for about 20 minutes, (remembering not to fall for the false ending to the first movement), then you’re on. The whole symphony revolves around a theme called the “idée fixe,” which represents a woman the composer loves, but who does not love him back. This movement depicts a glittering ball, in which the composer watches his unrequited love dancing with other men, so it’s important to play the quiet part after the “idée fixe” at rehearsal number 35 with the longing it requires, and to evoke the opulence of the scene, using lushly rolled chords and big sound. It’s a good idea to warm up your hands unobtrusively before you start the movement, and breathe deeply to keep nerves under control. It is best to learn this piece like a study when you have lots of time to play it slowly and frequently, and memorize the whole thing. In my orchestra, the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra (VSO), we usually do this piece with only two harps. Since Berlioz wanted at least four, and preferably six, harps for this, we double the two places where the other harpist is just sitting there. The infamous doubled arpeggio just before rehearsal number 30 (see ex. 1) can be played hand-over-hand, omitting the bottom line, since Berlioz himself realized that it did not sound good, and recommended against writing this way for the harp. The last page has repeated chords at a fast speed, which is very pianistic. The Cleveland Orchestra harpists used to split the top line of the last page between them, alternating beats, in order to maximize the sound. Once you’re done, you get to sit back and enjoy the rest of the piece from the best seat in the house. Enjoy it—you’ve earned it.

2. Tzigane

Along with Symphonie Fantastique, Ravel’s Tzigane was the only other part to make the top ten of every harpist we talked to. Tzigane (translation: gypsy) was commissioned and premiered by Hungarian violinist Jelly d’Arányi as a violin and piano piece, but with the piano having a “luthéal” attachment. The luthéal was a then new piano attachment with several tone-color options produced by pulling stops above the keyboard. One of these sounded like a cimbalom, which fit the gypsy-esque idea of the composition. The original score of Tzigane included instructions for these stops. By the end of the 20th century, the first print of the accompaniment with luthéal was still available at the publishers, but by that time the luthéal attachment had disappeared. It was orchestrated in 1924 and premiered by the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

It is not only challenging because of the pedal changes and the awkwardness of the hands, but because the opening cadenza has to be together with the solo violinist. Get a copy of the score, or at least the violin part, so that you are aware of the places where the violinist’s trills change in the harp cadenza. It’s almost impossible to keep an eye on the conductor when you’re playing all those notes, but your ear can help guide you. Cristina Braga, principal harpist of the Symphony Orchestra of Municipal Theatre of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil says this is a part you must not just know, but know well and from memory. “It’s impossible to read and play,” she says. “It is also almost impossible to look at the maestro and play.” Let your ear help guide you through all of those notes.

Emily Levin, who is in her second season as principal harpist with the Dallas Symphony, says this part was not only on the audition list, it was on every round of the audition. “It will inevitably be on an audition list, so why put off the inevitable? Happy practicing!”

It’s common for conductors to move the harp up to the front of the orchestra for this piece, so if they do, don’t forget to check your pedals again before you start. I have a friend who was so distracted by the furniture-moving that she forgot to reset her pedals from the previous piece, and spent the first part of the cadenza frantically searching around with her feet.

Strict adherence to the beat is essential when practicing this cadenza. Be aware of the accelerando at the end, where you must watch the conductor in order to finish with the soloist. And don’t forget to keep going! There’s no time to pat yourself on the back for a job well done until the last note of the piece is played.

3. The Nutcracker

Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker ballet (premiered 1892) is a staple of most orchestras’ repertoire. Every year with the VSO, we either play the entire ballet for visiting companies, or we do bits of it on our traditional Christmas concerts. The Nutcracker Suite for orchestra only includes the “Waltz of the Flowers,” for the harpist, but the rest of the ballet is full of exposed and tricky harp playing. Many audition lists have the cadenza from “Waltz of the Flowers” (or the “White Swan” from Swan Lake). Remember that the Nutcracker cadenza is not written as it is played. When you listen to recordings, you will hear some of the different versions of the cadenza. There is some freedom to roll the figures downwards, one hand after the other, or roll them in opposite directions, and to play the final arpeggio as a glissando or not. To see more details, look up my article, “Cracking the Nutcracker,” in the September/October 2015 issue of Harp Column.

Braga says the keys to this cadenza are sound, crystal-like articulation, and imagination. “Sometimes, between the 20 performances of this during a nice hot December, you may want or need to change a bit of your interpretation to bring in color and humor for your fellow colleagues with a longer chord, or a quicker, decisive glissando just to add a nice surprise and to keep everyone’s interest.”

4. Ein Heldenleben

Richard Strauss’ Ein Heldenleben (1898) is a very technical part. The title refers to a “hero’s life” and follows this hero through his critics (hilarious woodwind writing), his companion (wife), battles, his attempts to make peace, and his retirement and death. You can even hear his sword drop. Of course, the love music has the best harp parts! Strauss seemed to forget that harpists play with four fingers, so there are some figures that need to be edited in order to accommodate the five notes in the pattern. (see ex. 2) Since there are two harp parts, the harps are able to accomplish all the appropriate effects, despite some necessary editing. Strauss harp parts are often on audition lists because of their technical difficulty, but at least they are beautiful.

5. Concerto for Orchestra

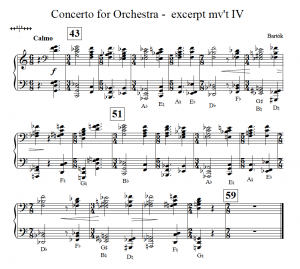

Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra has a wonderful harp part. I prefer memorizing the sections that are rhythmically and technically challenging so I can focus on listening to the rest of the orchestra. The fourth movement is especially important for harpists, notes retired Houston Symphony principal harpist Paula Page. “It requires clean playing, smooth pedals, and musical expression within the consistent eighth notes,” she says.

I highly recommend playing along with a recording before you get to the first rehearsal. I use enharmonics in the very chromatic part in the fourth movement, (see ex. 3) which makes it smoother. Marcel Grandjany came up with an alternate way to split the two harp parts at the very end of the “Finale.” Grandjany keeps the hands out of each other’s way by having harp 1 take the top lines of both parts, and harp 2 takes the other two lines of both parts. When auditioning, you must use the original, unless the orchestra has sent you the edited version. Beatrice Schroeder Rose’s book The Harp in the Orchestra also splits the parts differently for the first page of the final movement. In her edition, each harpist plays on both the beats and the off beats.

6. The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra

Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra (Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell) is tricky to count, and can be awkward to play. This is a perennial favorite for school concerts and children’s concerts, for obvious reasons. Britten was commissioned to write it in 1945 for a documentary film to introduce each instrument of the orchestra to the kids. There are two versions, and the opening variations are different, depending on whether or not there is a narrator. Hopefully, this will have been communicated to the librarian, who will have marked it into your part. The big harp “cadenza” at Variation I is not a cadenza at all; it is conducted and very rhythmic. It’s important to practice the whole piece with a metronome to make sure you don’t rush or drag. I use a specialized fingering at Variation I, (see ex. 4), while some harpists use extra pedals to obviate any wrong notes. The last two pages can be confusing rhythmically; it helps to say the beats out loud while practicing this section.

Levin says Britten’s brilliant writing for harp requires a specific skill set. “(It demands) exact rhythm, finger clarity, fantastic rolled chords—skills that are so helpful in bettering us as orchestral harpists.”

7. La Forza del Destino

Verdi’s Overture to La Forza del Destino (1862) is very popular with our audiences, so it comes back to haunt me on matinées, pops shows, main series, etc. Just before the harp is to start, the clarinet has an upbeat to the melody, which gives you the tempo. It can be quite fast, so prepare this piece by practicing it at speeds higher than you think it will go. In auditions, you play it as written, unless the part they sent you has been edited. But, in the orchestra, the main objective is to hear the moving upper parts and accompany the clarinet solo, so sometimes a bass note or two can be omitted in order to let the left hand help out the right. Eleven and 12 bars before H, you don’t need to leave anything out, but you can play the first beats in the left hand and give your right hand a break (see ex. 5).

8. Tristan and Isolde

Wagner’s “Prelude and Love Death” from Tristan and Isolde didn’t make my top ten, but was a popular choice among the other harpists we talked to. “This piece is beautifully written, and it’s extremely beautiful music,” San Francisco Orchestra principal harpist Douglas Rioth says. “To play it effortlessly and with good phrasing is very telling in a harpist’s musical abilities.” Braga adds that “Opera is wonderful in that it obliges you to play, listen to everything, know the entire piece, and follow the singer—keeping in mind singers are creatures of high freedom, and this is good, not bad.”

I had to learn this in university when I had only been playing harp for a year and a half. Luckily, I had three months, and I nailed it. I memorized it so completely that now, when it comes up, it is almost easy! The ending is technically the least taxing part, but musically the most telling. The tempo really slows down, going from sixteenths to eighth notes, and nine bars before the end, the melody has a triplet over your four sixteenths. I wrote out the melody on top of my part from 15 bars before the end, and I sing it when I practice this part.

9. Petrushka

Stravinsky’s ballet Petrushka, about a jealous puppet who comes to life (or does he?) is another one of those pieces whose harp part must be edited. It includes 10-note chords and chords with enormous spans. The part requires a great deal of forethought and practicing to familiarize yourself with the difficult rhythms and entrances. It is generally not on audition lists, perhaps because much of it is buried in the orchestration. There is, however, a cute little solo depicting an organ grinder in the town square. There is a larger, two-harp orchestration of this ballet (1911), though almost everyone does the later 1947 version, which has one beleaguered harp part. Even with the two-harp version, the harp parts are very awkward, and completely different from the 1947 version. So, make sure you find out which version the orchestra is performing before you assume it’s the usual.

10. Symphony in Three Movements

Another Stravinsky work, his Symphony in Three Movements, comes in at number 10 on our list. “This piece terrifies me every time I play it, so the more prepared I am before playing it, the better,” Levin says. “It’s technically challenging, musically intricate, and the piece itself is great.”

Page says in addition to the technical challenges, the part also presents significant rhythmic challenges. Sections of this appear on audition lists and Royal Conservatory exams. The harp part starts in the second movement, so there’s about a 10-minute wait while your hands get cold. The part is very exposed in many places, and usually is together with other important lines. This is one piece that really benefits from listening to it a lot, and playing with a recording. Be aware of where the exposed parts are. You can improve its playability with re-assigning the lines to different hands. The staccato at 116 and 122 is important, and is possible. The third movement is marked at 108 to the half note, but we did it at 138 the last time, and the presto went at 168. At least some of it is thickly orchestrated. The harp coordinates with the piano in a couple of very technical passages in the third movement. Watch out for 152, 157, and 172. At 152, it says “étouffé.” There’s no time. Play it normally and try for a dry effect. Some of the spans are obviously impossible for any hand, no matter how big, i.e. at 166. Leave out the top note.

Honorable Mention

There are a few more harp parts that didn’t make the top ten cut, but still got some votes, including one from my personal top ten, Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy. It was originally called Fantasy for Violin and Orchestra and Harp on Scottish Melodies, Op. 46, but a later edition whittled it down to “for violin and orchestra.” It’s a shame that the title was changed, because the harp part is very exposed and technical and must be practiced as if it were a concerto. No extra pay or star dressing room is forthcoming, though, if it’s just an exposed orchestra part. Often, the harp is brought to the front of the orchestra so that the violinist and harpist can hear each other. The harpist often accompanies the violin melody, so you must really listen and respond sensitively. The third movement can go extremely quickly, and is written very pianistically, so it may be necessary to edit out some notes (see ex. 6). Though this is a very demanding part, it is also very rewarding.

Chabrier wrote España, originally called Jota, in 1883 after a trip to Spain. It is a scintillating audience favorite. Many orchestras play it very fast, so the big arpeggios before rehearsal E become a blur. Don’t worry if you have to omit a couple of notes in these; they are an effect. Spanish music is very rhythmic, so it is essential to practice with a metronome. There is a very exposed solo after rehearsal letter A (with horns and a second harp) at the bottom of the first page. This requires a fingering that won’t confuse you, but still brings out the guitar-like sound. Don’t let the orchestra make you attempt this piece without a second harpist. Several cuts would be necessary in order for that to work.

The harp part in Holst’s seven-movement work The Planets is hugely important and exposed. “Mercury” has some very awkward writing, which I slightly alter to make more user-friendly (see ex. 7 on pg. 37). The woodwinds cover the harp in this spot, so it does not sound bare. Cues are very useful where there are many repeats of the same pattern. In “Saturn,” there is a section that is best memorized or cut-and-pasted and folded out, since there are a couple of bad page turns. The ending of “Saturn” works much better if split differently between the harpists (see ex. 8). This piece is very popular, so your time will be well spent learning the part. In some editions, there are some mistakes. The worst one is in “Uranus,” 11 bars after rehearsal 2 in the second harp part. The top chord in that bar should be on the fifth beat, not the sixth.

Harpists can’t ignore pieces with a harp cadenza, and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Capriccio Español has an important one. Rioth points out that the cadenza is not particularly well written for the harp, being awkward to play and unimpressive to listen to. “I very much like playing and hearing the Salzedo version of the cadenza,” he says. “Undoubtedly, Rimsky-Korsakov would agree that it sounds better than what he wrote.” I like to play the cadenza as written, imagining a flourish of ruffled skirts and zapateado.

Rioth adds that the last movement is also challenging to play, with its fast left hand and quick jumps in the right hand, making it a top pick for audition lists, along with the cadenza. Page notes that this part is a good way for audition committees to hear how harpists play glissandos.

Speaking of cadenzas, the harp cadenza from the opera Lucia di Lammermoor is another important part to know. “Even though this is not normally performed in an orchestra other than opera orchestras, it is the best excerpt for showing musicianship and control,” says Page. Braga observes that cadenzas are “small windows” into the individual. “Remember, you have to sing and use imagination, all with pleasure. Music should be in every note.” She goes on to add that tuning of high notes is very important.

Levin calls the fourth movement of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony the “quintessential” harp part. “For appearing straightforward, it demands so many skills—beautiful tone, exact rhythm (within a musical suppleness), hearing strings in your head while playing, and musicality. Also, it’s one of the best examples of orchestral chamber music,” she adds.

Mahler symphonies are a top choice for all orchestras in the Netherlands, including hers, says Ellen Versney, principal harpist of the Radio Philharmonic Orchestra of The Netherlands. “Personally, Mahler 5 is the orchestral work I must have played most during my career, and all over the world too, as it is a much loved piece to play on tour.”

Levin admits that Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun is not the most difficult part, but it is especially important for young harpists to learn. “I remember my first time playing this piece in youth orchestra, holding my breath and counting frantically, because our guest conductor was more about interpretative beats than actually giving us downbeats,” she recalls. “As I grew more familiar with the part, it was such a relief to realize I knew exactly where my part should fit in with the orchestra! This is one excerpt that I think takes multiple performances to really learn how you connect with the orchestra—especially when you’re a young harpist—and the earlier you start learning it the better.”

Along with Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker cadenza, the iconic cadenza from his Swan Lake ballet is a must-learn for harpists. “One of these (the Nutcracker or Swan Lake) is on every audition, and though similar, both should be learned. They are the most familiar excerpts to audition committees,” says Page.

The “Dance of the Seven Veils” from Richard Strauss’ opera Salome is an exposed and challenging part that tends to show up on audition lists. “It’s been on almost every audition I’ve taken, and after so much exposed solo playing in a practice room, it’s almost a relief to play it with orchestra,” says Levin. “Plus, you can always benefit from practicing this excerpt.”

Some of these parts are inevitable for all harpists in the orchestral field. Even if you are not planning to audition for advertised orchestra positions, it’s fascinating to look at the repertoire list for their auditions and work on those pieces when you have the chance to do so with no pressure. •