Double Duty

Find out how three harpists did Double Duty to combine Harp 1 and Harp 2 orchestral parts in this article extra.

Sitting in the practice studio, I stared at the two harp parts on my music stand, wondering if I could clone myself. How would I keep my place in the music, count, watch the conductor, and what about all the pedals? The professor for my conservatory’s conductor’s orchestra instructed me to play what I could from the Harp 1 and Harp 2 parts of Debussy’s L’Après-midi d’un faune (Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun) for a reading so student conductors could practice. I saw that the two parts would either respond to each other or play exactly the same notes. It wasn’t terribly difficult, and I felt a responsibility as the harpist (or perhaps in this case, the entire harp section) to write a single harp reduction that combined the two parts as much as possible for the student conductors to better hear the entire harp part. After combining all the notes, considering which part was more important at different sections and navigating the pedal changes, my Debussy One Harp Reduction was born. The professor was delighted that it worked out, and the reading led to a performance for the student conductors.

Going it alone

I do not believe that the use of one-harp reductions should ever become the norm. However, these requests are unavoidable…

Combining orchestral harp parts is not new in the harp world. I’ve often heard stories of harpists who were courageous enough to take on Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique with one harp. (Two of them include Karen Rokos and Morgan Short—read more about their experiences on pg. 27.) For The Nutcracker ballet, one harp seems to be the rule rather than the exception. Smetana’s Vysehrad includes both parts into one score, and it is not at all impossible for a single harpist to play.

Some community and amateur orchestras started requesting my score for the Debussy One Harp Reduction. Similar to many other harpists who have received these requests, orchestras ask for a combined part due to the scarcity of harpists in the area or a tight budget as an amateur orchestra. Some harpists have even been offered double the pay to make it happen, and these reductions allow orchestras to program a work which would originally have been impossible without two harpists.

As much as we all love having a harp section, I personally find that playing as a one-harp section can occasionally be more reliable. There is less worry about the togetherness of rolled chords or the matching of tones, as I only need to rely on my skills to execute the part. When there is a section, I can absolutely be a team player. Yet we must agree that sometimes, two harps are not better than one.

Just because we can, does that mean we should?

However, should we be encouraging the use of combined harp parts, and should we even agree to these types of gigs? It is unlikely that a violinist or clarinetist would be asked to play both first and second together, and it seems ridiculous that harpists get these types of requests. Composers must have considered both technical and aural reasons for scoring two harps in their works, and reducing the harp section changes the composer’s intentions. Furthermore, it diminishes the power of having multiple harps on stage. Two harps playing the same notes in Smetana’s Vysehrad would sound completely different than one harp. Berlioz had originally wanted four harps for Symphonie Fantastique and reducing the firepower of four to two to one changes the sound dramatically. Allowing combinable parts to happen might encourage the idea that it could work for all two harp parts and create unnecessary pressure amongst harpists and ensembles. While it is possible to combine some, we must remember that it would be quite impossible to combine the parts of Gustav Holst’s The Planets, Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloe, and many others. The composers did score for two harps for a reason.

Practically, these requests also reduce the number of jobs for harpists. Harpists already compete for a singular position in an orchestra. Taking away the necessity of a second harpist would make things even more competitive. Additionally, the harpist is forced to not only rearrange but also relearn the orchestral part, meaning extra time and energy to make it work. To play both parts together, it is also likely that the harpist needs to be very competent technically and musically. Just imagine playing the entire opening of the Berlioz on your own! Quick feet and great composure is absolutely necessary to nail all those arpeggios.

Occasionally, it is unfortunate that some harpists are forced into these situations simply because the orchestra did not want to hire another harpist. Once, I arrived at a Nutcracker rehearsal thinking there would be a second harpist. After all, the orchestra only sent me the first harp part and it was after the first rehearsal that I realized they had only hired me. The professional in me could not bear to leave out so much of the music, and, eventually, I chose to play both parts for the final performance.

Rewriting and relearning the Nutcracker parts took me much more time than I imagined. While I don’t know if I would have spent my own money for such a part, I would have loved it if there was one readily available to consider. My hope is that in making my One Harp Reductions available, it could become a great addition to the resources a harpist could have and also save harpists the time to write out these combined parts.

I do not believe that the use of one-harp reductions should ever become the norm. However, these requests are unavoidable, and most harpists will encounter these dilemmas at some point. In order to navigate them, I take you through my arrangement thought processes and share some tips to aid you in combining two harp parts into one.

Prioritizing parts

For works like Debussy’s L’Après-midi d’un faune or Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, the two harp parts are fundamentally different. It is unlike the doubled harp parts of Shostakovich or Strauss because they feature call and response ideas between the harp section or complementary musical ideas at the same time. To combine parts, one needs to consider which part is more important than the other, and how much to include or exclude while still remaining playable.

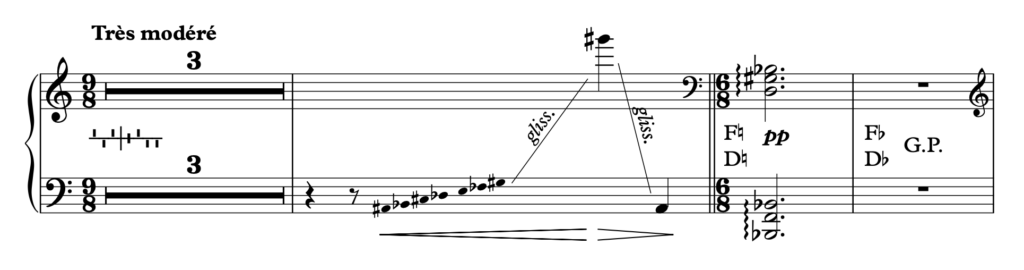

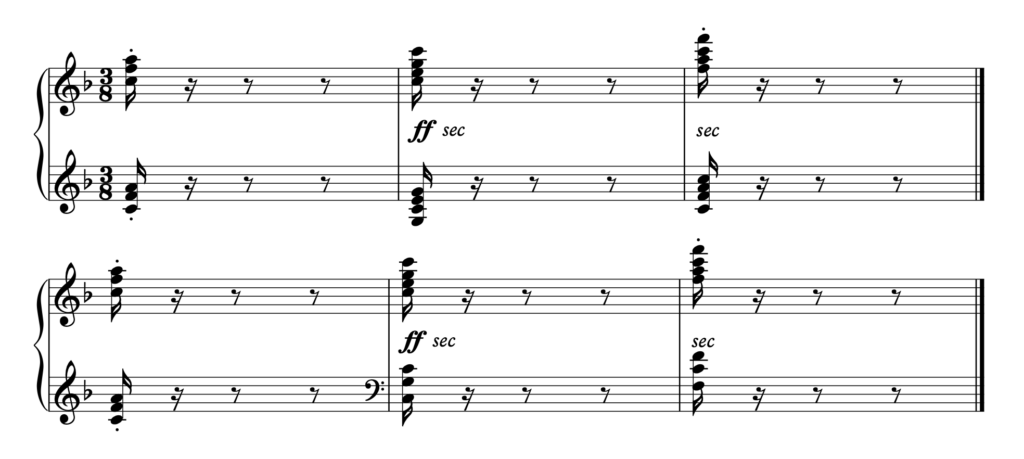

In Debussy’s L’Après-midi d’un faune, I decided that the call and response ideas of the beginning were important. Harp 1’s (H1) opening glissando answered by Harp 2’s (H2) low bass chords and the rising arpeggios in rehearsal 2 can easily be combined with some practice and alterations. Pedals have to be set to achieve the specific tonality of the H1 glissando and thankfully, the H1 glissando has a G#. This allows the H2 chord in m. 5 and 8 to be realized with the G#/Ab enharmonic and only two pedal changes of F and D (see example 1). Rehearsal 2 is more straightforward as the harps do not play together and can easily be combined. The tricky part of this combination is the additional jumps of register one needs to make, which simply means more practice.

However, I have seen other Faun reductions which included much less than I did. Often, the H2 chords in m. 5 and 8, and the downbeats of m. 23 and 26 are omitted. The pedal changes in m. 5 and 8 are at risk to sound unclean because of that unintentional pedal slide sound which we are all familiar with.

It’s possible to combine the parts at m. 23 and 26 to play as much as possible (see example 2), but removing the downbeats of those two measures eliminates one jump and is certainly a safer option if the tempo is on the higher end (see example 3). Additionally, these chords and downbeats occur when other instruments in the orchestra play and thus might be less important to include.

Both versions of this reduction are entirely acceptable. Personally, I enjoy including as much as I can from both parts. However, this means additional practice to ensure that my pedal changes are clean and my jumps very secure. Omitting the notes is certainly a good way to alleviate those worries but also means changing the music Debussy wrote. Either version will work well and it just depends on the facility, time, and priorities of the harpist.

Aside from four measures in rehearsal 7, the remaining sections of Faun were easy to consider. Combining the harmonics and notes in the measure before rehearsal 6 is not at all technically difficult, and rehearsal 9 simply requires pre-planning of pedals to nail that H2 glissando—things that harpists are used to anyway! Much of the music in L’Après-midi d’un faune is tutti and mostly requires the single harpist to find the appropriate balance within the orchestra.

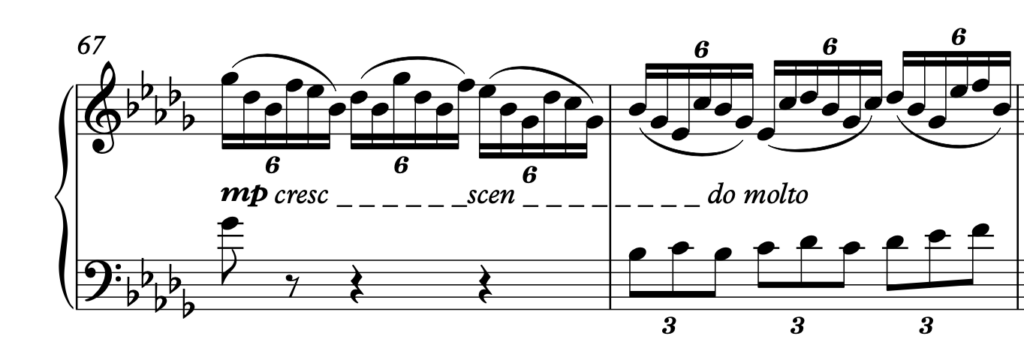

The trickiest section at m. 67 needs a closer look. (See example 4.) Here, the two harps play different notes, and it would be too complex to attempt to play both parts. I had to instead consider which part was more important or more interesting. In this section, every instrument is playing something different to create texture and highlight Debussy’s use of heterophony. Admittedly, the H1 part always threw me off balance due to the irregular figurations and H2 would have been the easy way out with its straightforward rhythm. However, the H2 part was already being doubled by the winds, and the H1’s irregularity was what made it more interesting texturally. Ultimately, what I chose to do was to utilize the entire H1 part but include the bass figure of the H2 part at m. 68 and 70. Though it involves a little more practice to execute, the bass line can easily be omitted if the harpist does not want to do so.

Enharmonics are your friend

The nature of Debussy’s writing made the two harp parts of L’Après-midi d’un faune quite easy to combine. However, this is not the case of many other works and different considerations will arise. Enharmonics become a very useful tool to include more of each part and navigate trickier pedal sections. For example, in Scene 8 of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, enharmonics allow for easier navigation between the H1 and H2 parts. Of course, it might mean that sharps have to be used as opposed to flats, creating a slightly different sound color than was intended. However, since the aim is to combine the two parts, you can justify forsaking certain sound qualities to achieve the larger goal of combination.

To add notes or not to add notes

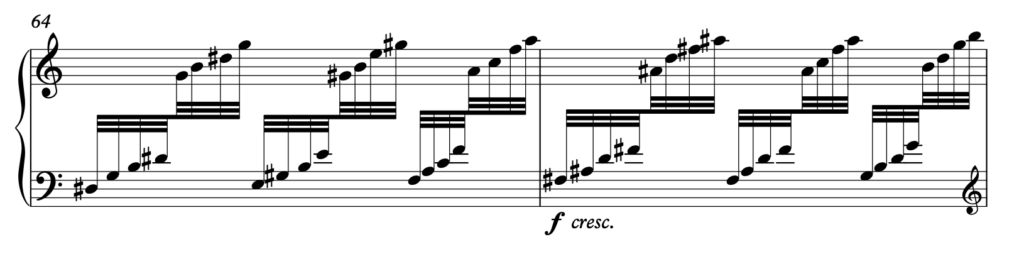

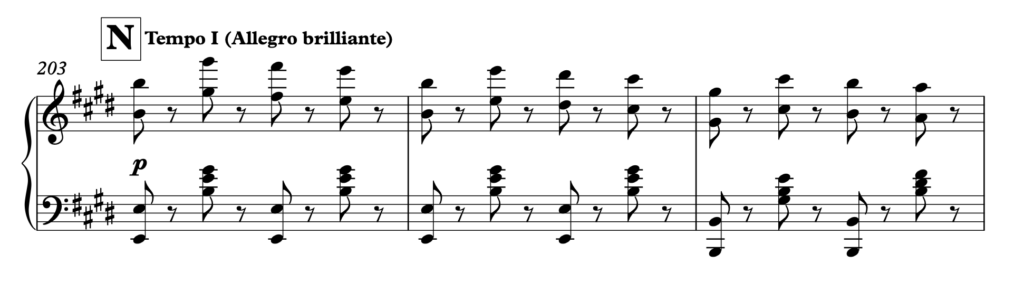

In a work like Verdi’s La Forza del Destino, the H2 part adds to the orchestral texture by utilizing chords. These chords can be combined with the H1 part to imitate the thicker texture of two harps in rehearsal N. Of course, we must remember that Verdi is one of our harp excerpts and adding more notes to it would make it much more challenging. We must also remember that the dynamic levels would still remain limited with only one harp playing. Including more notes for pieces like Verdi would make things more demanding for the harpist, and is ultimately a personal choice you have to make.

Making it register

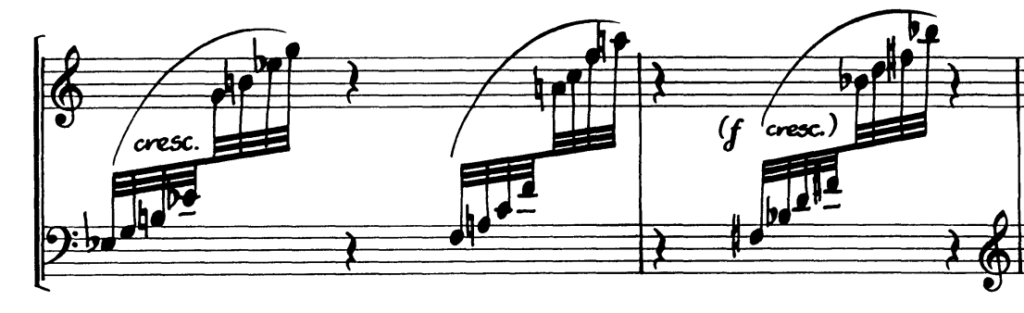

Other compositional methods to increase texture include playing the same notes in multiple registers. This is the case for Chabrier’s España where H1 often plays an octave higher than H2. When it is impossible to play everything, I often choose the part with the higher register as it will be more prominent. If there are multiple registers between both parts and both hands, like in España’s final three bars (see examples 7a and 7b), I would still choose the highest register to be played in my right hand and have my left hand play either the middle register to add volume, or the lowest register to showcase the full range that the composer used (see example 7c).

Playable or impossible

The final but most important consideration in combining parts is the playability of it. How much should one combine that it still remains possible for the harpist to play? Plus, is there enough time for the harpist to learn this “new” part? Theoretically and ideally, all parts can be combined and played if we just had the time to practice it. However, one has to remain practical when making these one harp reductions. The ensemble is already asking for you to rearrange some music and learn new parts in a limited amount of time. Consider carefully how much you are willing to leave out of the score and how much time you might have to learn a new part?

Combinable harp parts can be a means to an end. It allows for these works to be programmed where harpists are scarce or orchestral budgets are limited. However, it does reduce harpists’ jobs, creates more work for the individual harpist, and changes the composer’s original intentions of using two harps. By no means is this an encouragement for all two harp parts to be combined; but realistically, these requests do happen, and often harpists would do what they can to help the ensemble. Hopefully, these tips can help as you navigate these pragmatic issues and technical considerations when combining parts. Whether you choose to play for these ensembles, to combine two harp parts or even just to play the first harp part, it is ultimately a personal choice. I do what I can to feel content with what I play in the ensemble. After all, that’s my responsibility as a harpist. •