It’s 11:14 p.m. on a Monday night, and I am heading out my front door because I know that I need to take a walk right now, even if it’s just around the block. A cloud of anxiety looms above me, threatening to overwhelm me. There’s a tightness in my chest and throat. Why these intense feelings? It’s all very familiar, and I have felt it before. The cause seems so harmless when I examine it upon my return home: it’s only a pile of paper. It’s only a very thick pile of paper with music printed on it. It’s only a stack of 90 pages of orchestral and choral music that I have to learn in the next two weeks! Next to that, a couple of solos for a different performance. Next to it, a stack of chamber music for yet a different concert. Dun dun duuun! Cue the scary music…no pun intended. Well, it need not be so. Learning or keeping up a lot of music at once can be stressful, but there are ways to make it easier on yourself. Much of it has to do with organization and metronome work. Read on for steps to help yourself stay ahead of the game in your preparations, and to discover key strategies for learning a lot of repertoire at the same time.

Step 1: Take a deep breath and a walk

Although it may have seemed like it was only a dramatic hook to get you to read this article, taking a walk is my real and true advice. Every time I agree to take on a concert with lots of challenging repertoire, I make sure to build in some good exercise if at all possible. Staying physically active is an important element of practicing or studying music. If you sit in a practice room all day without much movement, you miss out on the memory, learning, and mental health benefits that exercise can provide. In a recent episode of The Bulletproof Musician podcast, host Noa Kageyama explains how science backs up these benefits. Studies have shown that exercising before and after practice sessions can make a real difference in practice performance, enhance motor skills, and even affect retention of learned material. In 2023, a team of researchers (Jesperson et al.) conducted an experiment proving that people who exercised before and after completing a task and then not practicing the task at all for a week, retained most of their learning gains with little to no decline in their skills. A 2015 study (Statton et al.) found that it’s best to exercise in short bouts both before and after a practice session as positive effects can start to decrease after an hour. Exercise of moderate intensity is best before a practice session, and if you’re also going to do some cardio after practicing, that’s when you can go for a more high-intensity workout in order to truly reap the benefits.

If you are unable to schedule exercise around your practice sessions, start with a simple walk instead. Focus on your breathing as you walk. Perhaps it is chilly and you can see your own breath. Maybe the sun is keeping you warm. Wind in the trees and plants, stars at night, or the color of the sky are all great details to focus on as you ground yourself before you begin thinking about the work ahead. Being out in nature and getting some fresh air is an instant reset for your mind, and the exercise gets oxygen flowing to your brain so you can focus.

Step 2: Stay ahead of the game and ask for what you need

Being organized and prepared is key to learning music efficiently. The best tip to stay ahead of the game is to get all your music as far in advance as possible. This is easy when you are the one planning a solo or chamber music recital. You can pull things from your library of music early on and make sure it is neatly marked with everything you need to succeed in your practice sessions. When playing with an ensemble or orchestra, getting music ahead of time isn’t always something you can control. Orchestral libraries may rent certain parts or perhaps don’t yet have some of the very newly written repertoire ready until closer to the actual rehearsal period. No matter what the situation, don’t be afraid to ask for what you need and reach out ahead of time. Only you truly know how much time you require to be comfortable in your preparation.

Step 3: Look at the bigger picture

Context is everything in music preparation. Learning a new solo in a month is one thing. Learning a new solo and three orchestra parts, a chamber music piece, and a new solo commission is another. Looking at the bigger picture is an important step in the planning process. If you have several different concerts that will take place during the same month, figure out which one has the most demanding repertoire before you begin your preparations. This will be easy to do once you have all your music. You can rank the repertoire based on difficulty. You can also factor in what music you have already played or performed in the past, where your muscle memory will aid you. Relearning a piece, even if it is difficult, may require a totally different and much shorter timeline than learning new notes and patterns that have never before been in your fingers.

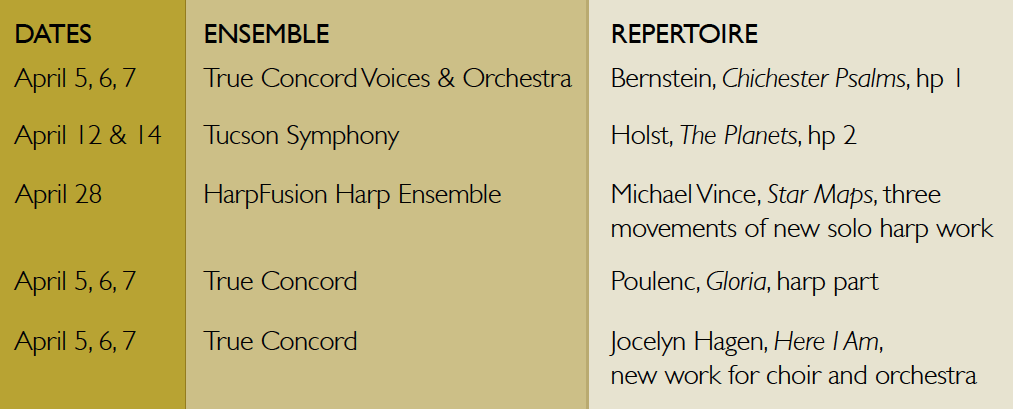

April 2024 performances

The example above is from my own freelance experience, taken from a month where I had three different concerts in which I happened to be performing repertoire that I had never played before.

As you can see from the example, I wasn’t necessarily working in the order of the performance dates, and one concert was split within the chart because I prioritized based on the difficulty of each piece of repertoire. Without getting into too many details, there were many subcategories within each of those examples. Chichester Psalms has three movements, so I worked out which one was most challenging and started with that one. Here I Am has four movements, one of which I knew I could sight read, so I didn’t spend time on those pages, other than running them right before the first rehearsal. The Planets has seven movements, most of which are difficult and contain lots of exposed harp sections in both harp parts, so that piece moved up to second place on my list in order to ensure that I could be a solid support for the principal harpist. My university production with HarpFusion included a few solo selections, which I prioritized in third place, as I personally find solo harp performances more stressful and prefer additional time. This type of plan should be tailored completely to you and what you know about your own strengths, weaknesses, and what you want and need out of your preparation process.

4: Prepare your music

Preparing your music so it’s ready to play will save you a great deal of time in your actual preparation. Marking all of your music is crucial so that when it comes to practicing, you won’t waste any time writing in major fingerings, pedals, pedal diagrams, or tempos. Sometimes you need a whole practice session to play through something in order to get markings into your music and try out different fingerings. It’s important to do this at the very beginning. Any minor changes can be made later as you are deeper into the learning process.

5: Sit and listen

It’s easy to get physically tired when preparing a lot of different performances at once. You may feel so exhausted at times that it’s difficult to summon the energy to practice as much as you would want. That’s when it’s time to sit in your most comfortable chair with a beverage of your choice and get out your good headphones. Listening is an effective and fun way to mentally practice. If you are preparing for an ensemble project, listening can reaffirm your role in the piece. You will be able to write in detailed cues and feel secure in your knowledge of each entrance because you will know what the piece sounds like and what comes next. Even a solo can benefit a lot from listening to different interpretations as you follow along with your music, perhaps even working on committing it to memory.

6: Use your metronome to your advantage

At the heart of all of these strategies lies one indispensable tool. What ties all of these elements together? It’s your metronome! You can see that it will apply to every area of preparation mentioned, except the walk. (Although, it never hurts to walk in the rhythm or tempo of something you are playing. You’ll be truly living your music!) Even when you’re just listening, a metronome is a helpful tool for tapping out and finding the exact tempos. You can also use it when preparing your scores. A note of your exact number of beats per minute helps you efficiently find and remember your tempos. Having those markings allows you to prioritize certain sections of your various programs, as faster passages can be more challenging. All in all, your metronome is your friend forever and always. Here is a helpful way to use it when you’re feeling pressure to get various sections up to tempo in a short amount of time.

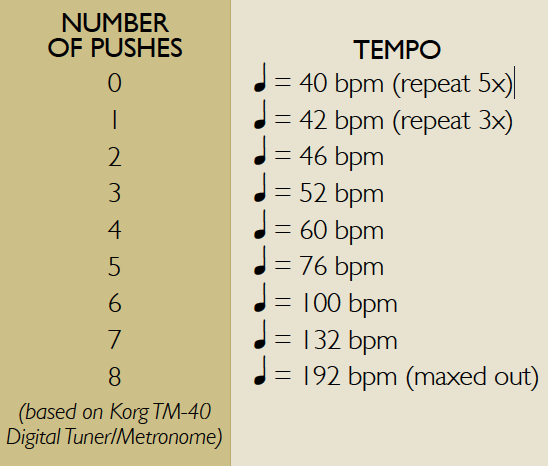

The Exponential Metronome Strategy

Let’s talk about “exponential” growth. What does it really mean? The term is often misunderstood to mean rapid growth, when in fact something growing exponentially can be growing slowly at first. This is exactly why I like to use this word, though it is in quotes because nothing else about the method has to do with the mathematical concept or its formulas. I promise, it is very easy to follow! I came up with this strategy while using a standard Korg TM-40 Digital Tuner/Metronome while practicing. This metronome has pre-set numbers for its beats per minute (bpm), so each time the up or down tempo buttons are pushed, certain numbers appear automatically. Typically they are numbers often found in real music as common tempo markings. This particular metronome is limited from 40-208 bpm. Many metronome apps these days can go up to a much faster beat per minute tempo, but you won’t need such a range for this strategy. Any metronome can be used; simply follow the numbers below and input them manually if they don’t appear in the order described.

To begin, set your metronome to the lowest possible tempo, which is generally 40 bpm. You can start out by working 40 bpm to the quarter note, but if that still feels too fast, switch to eighth notes or whatever value makes sense for the section you are working on. You’re going to play the tricky passage at this slow tempo five times. An amazing harpist once told me that you can’t play anything fast if you can’t play it slowly. This is generally true, which is why it’s great to take time and do a few more repeats at the slowest tempo.

Start: Quarter note or eighth note = 40 bpm

Next: Push your metronome button up one “click” to 42 bpm. Repeat the passage three times, as you are still luxuriating in a very slow tempo where everything can be accurate and you can solidify your technique.

Next: From the 42 bpm tempo, push your metronome button twice, or up two clicks to 46 bpm. Now it’s time to play each upcoming tempo just once, unless you feel you want more repetitions or you have arrived at your final tempo and want to solidify.

Next: Push your metronome button three times, or up three clicks to 52 bpm.

Next:Push your metronome button four times, or up four clicks to 60 bpm.

Are you beginning to see the idea behind this? Each time you add an extra push, the tempo gradually becomes faster until it is very rapidly growing. The tempo orders are shown below and can become memorized by rote if you make this a learning routine. Use only what you need for a particular section of music. Perhaps what you are playing is marked at a tempo of 76 bpm. In that case, end at 76. Perhaps 60 bpm is already a bit too fast. In that case, you know you’ll be solid when playing something marked at 54. The chart above uses a quarter note as your main beat, but once again, this can be adjusted depending on the time signature and tempo of the piece in question.

Sometimes, depending on the passage, you will end up “maxing out” the metronome around the 200 bpm range, meaning there is nowhere left to go. In that case, it’s a good idea to reevaluate and perhaps repeat the strategy by using a different note value if you haven’t achieved a fast enough tempo yet. Whatever you decide to use, you will probably notice that the toughest jump is usually from 60-76 bpm or 76-100 bpm and beyond.

In order not to get stuck in a rut with an almost-there-tempo, try playing something at a faster tempo even if it falls apart. Then you can use the same strategy but working backwards. This is a great way to teach your music-learning brain to be flexible and approach your goal tempo from the other extreme. You will see that over a few days you won’t need to go so many clicks backwards anymore as the connections are made between your brain and your muscle memory. This idea is also explored in Noa Kageyama’s Bulletproof Musician podcast. Be sure to check out the episode with trombonist Jason Sulliman: “On Why Fast At-Tempo Practice Can Be More Efficient Than Slow Practice.”

The busy schedule of a freelance musician often requires learning new music with a very quick turnaround. Learning piles of repertoire at the same time can be tough, but a combination of each of these methods will help you streamline the process for maximum efficiency. Focus on accuracy first, but don’t forget to enjoy your role in the music by listening to your repertoire. If you just remember to put on your walking shoes and make sure your metronome has fresh batteries, you’ll be well on your way to many rewarding performances! •