The teachers

Isabelle Perrin (left—photo: Pål Laukli) has had a rich solo harp career playing with orchestras around the world. In addition to her performing career, Perrin is dedicated to sharing her expertise with others. Since 2013 Perrin has been Harp Professor and Head of the Strings Department at the Norwegian Academy of Music in Oslo, Norway. Perrin has also taught as a harp professor at the Conservatoire National de Region in Nantes, France, the Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris, and has conducted master classes globally.

Heather Downie (right—photo: Imagine Images) is a musician who has brought fresh innovations to traditional Scottish music through her solo performances and collaborations with various bands. While she enjoys performing, her true passion lies in teaching and helping students learn. Downie currently serves as the Principal Scottish Harp Tutor at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, where she has been teaching since 2011. In addition, she runs her own school, offering private lessons in person and online for students of all ages.

Practice—there is no denying it is the key to unlocking a musician’s full potential. As harpists, we invest huge portions of our lives in practice—improving technique, honing articulation, and deepening emotional connection with our instruments. But let’s face it, it’s hard to gauge our progress objectively. It’s easier to see the gains made over longer periods of time, because improvement often comes in very small daily increments. Practice is more of a trek across a continent than a weekend city getaway, so we decided to follow some harpists’ epic practice journeys two years ago to track their progress. When we asked for volunteers to participate in our Practice Makes Harpist survey, the response was overwhelming. We have shared the stories of ten harpists in an article series in Harp Column over the last two years.

At the same time, we also followed the progress of 123 participants through a weekly survey in which harpists reported their practice progress. The group ranged in age from 11 to over 70 years, with a mix of harp types, playing styles, and professions. Nearly half of the group reported practicing between one to five hours a week, fitting their harp time in between jobs or classes.

We’ve pulled the most interesting results from the survey and asked two top teachers to weigh in on the findings to help us integrate the takeaways into our personal practice regimen. Classical pedal harpist Isabelle Perrin shares from her wealth of teaching experience at the university level and lever harpist Heather Downie contributes a teaching perspective for all levels and ages.

1—Practice at the Right Time

Circadian rhythms, or the body’s internal biological clock, fluctuate in daily cycles affecting sleep, memory, and alertness. The human energy schedule has peaks and troughs. Everyone’s body has natural energy cycles, which can significantly affect productivity. Studies by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have found that most people are naturally at their best a few hours after getting up and around 6:00 p.m., with lows around 3:00 p.m. and before sleeping.

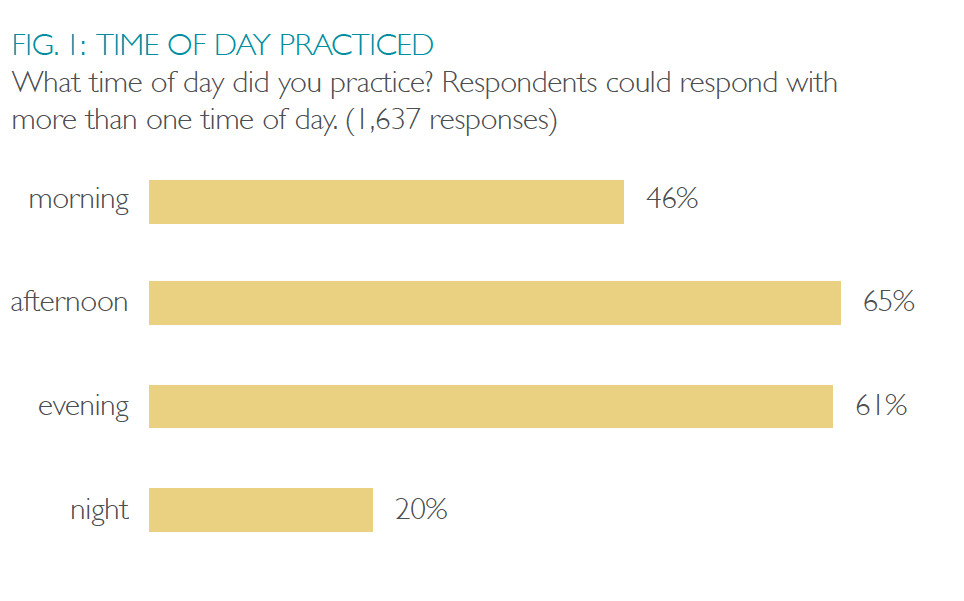

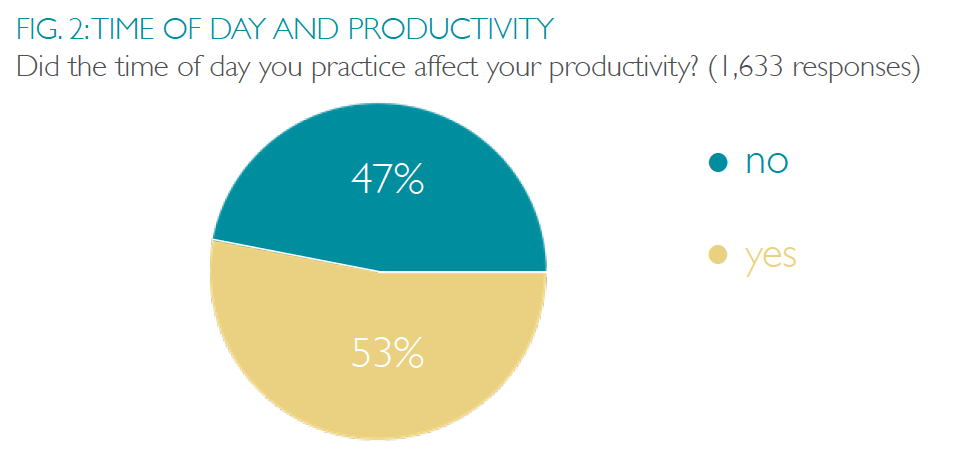

To measure how circadian rhythms affected participants, they recorded what time of day they practiced throughout the week (see figure 1) and whether the time they practiced impacted their productivity (see figure 2). It’s also clear that the most popular practice times are afternoons and evenings.

Improve Practice with less energy

In general, your energy level will affect your practice productivity. Forcing practice when you’re tired will take more effort and could be counterproductive. Perrin asks her students to find the best practice times for themselves because everyone’s physical and mental energy fluctuates differently, and by understanding these fluctuations, you can choose the content of your practice session accordingly. Perrin suggests, “If you find that you’re at a lower mental energy, maybe use that time for something like sightreading because doing a new or different activity helps the brain to focus differently and better. Perhaps you’ve practiced a lot already, and you’re physically tired, then switch to table work and use that sharp mental focus to fully understand the score.”

Setting a practice schedule can also take advantage of your energy level to boost productivity. Downie notes, “Students who have actual practice schedules, with committed times to practice, are more productive.” Even if your scheduled practice block is only ten minutes each day, those ten minutes add up to over an hour a week and more than four hours a month. It may seem small, but even a little bit of practice is more productive than zero.

To find your optimal time to practice, try these three steps.

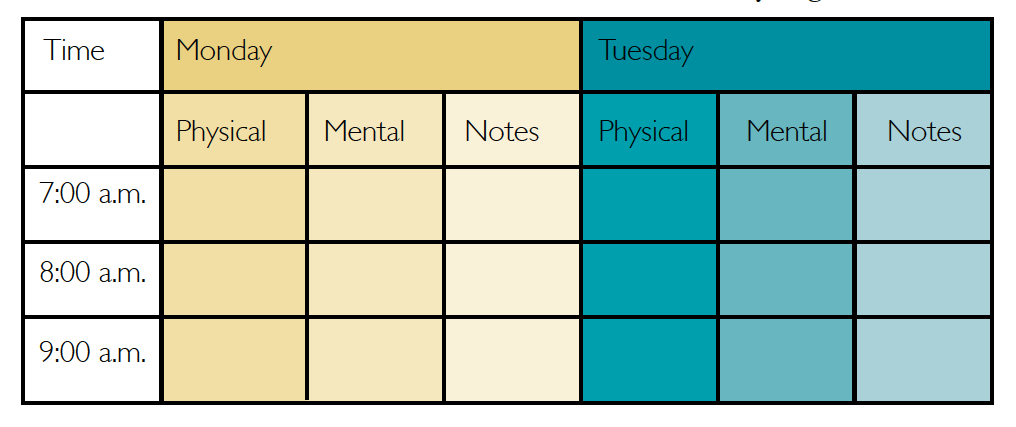

1. Track your physical and mental energy. Make a table similar to the example below. Set an alarm to remind you each hour to record your physical energy level from 1–5 (one is very tired, and five is your top physical energy level and mental energy level) and your mental alertness from 1–5 (one is unable to focus much and five is at top form). After two weeks, you should see some patterns emerge, showing when you’re most awake and alert. Remember to turn off that alarm when you go to bed.

2. Pick practice times. While full-time professionals often have more control over when they practice, we all have obligations that likely demand our time when we’re most productive. Amateur harpists who are early birds may have to save morning practice for the weekends. In addition, if you need to practice during a time of low energy, you could start with some physical exercise and break up the practice more often by getting up and moving around. Some like a quick walk, and others recommend a quick dance to get the blood flowing.

3. Match your mental and physical state to your practice. Consider what needs to be practiced, then check in with yourself at the beginning of the practice and try to align your practice goals and energy level.

There is something the survey didn’t touch on: a large elephant in the room or, in this instance, under the bed. Sleep has a massive impact on our perspective and our productivity. Research from Harvard Medical School finds that those who enjoy a good night’s sleep do better on tests than those who don’t. Scientists study a phenomenon called “social jet lag”—how work, study, and social activities disrupt our sleep patterns. One study from the National Library of Medicine notes that around 70 percent of people in developed countries function with one to two hours of social jet lag. That’s like flying across a few time zones every weekend. Getting quality sleep on a regular basis will affect more than your harp practice.

2—Repertoire: Renew, Revise, and Repeat

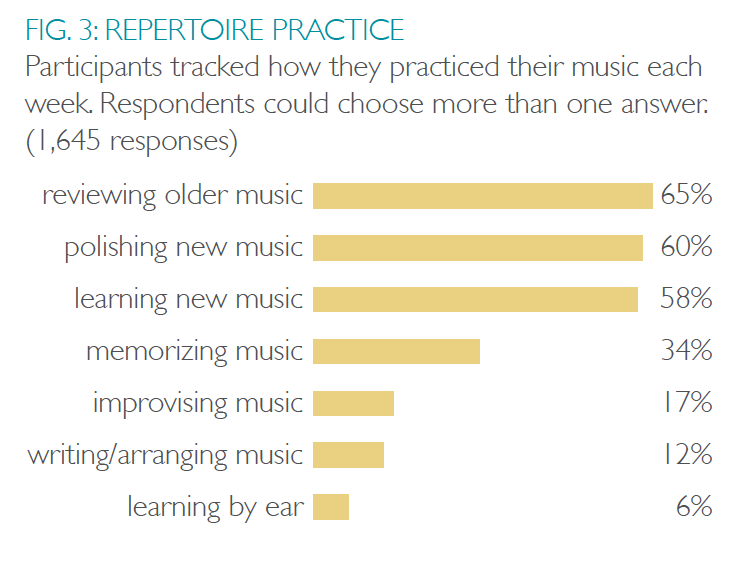

Most of us harpists are here to play great music, not to practice scales and arpeggios. Repertoire practice is often the central, most exciting part of our practice. In the survey, participants recorded weekly how they practiced repertoire. (See figure 3)

The amount of repertoire people practiced remained the same throughout the year we tracked. After the survey ended, 12 participants took part in final interviews to give more detailed feedback about their practice experience. During these interviews some participants noted changes in how they approached repertoire. Pennsylvania-based adult harpist Brandy Babcock started playing harp three years ago. While tracking her repertoire practice throughout the year she says she gained some insight into what motivates her. “I need to have multiple different events scheduled during the year with different repertoire focuses to be able to have a more intrinsic motivation to practice, progress, and learn a variety of new music. Otherwise, I would dabble and ‘squirrel’ my way through various pieces, playing them, forgetting them, and not polishing them to performance quality. Before the study, I hadn’t recognized this pattern, and it really helped to know what best motivates my practice and progress.”

Harp practice and shopping have something in common. When you buy a new shiny object, such as the perfect music stand, you admire it for a few weeks before the novelty wears off. Similarly, with a new piece of music, the dopamine hit of something new can be exciting for a time, but eventually, the novelty fades. Downie says she often sees this phenomenon. “Since more teachers have started offering online options, I have noticed my adult learners find it more difficult to stay with a piece until they’ve actually gotten benefit from it. I don’t even mean until they have it performance ready. I actually mean until they have mastered the technique well enough that I think they’re going to be able to apply it in a different piece.” Downie notes that to maximize the long-term technical benefits of learning a piece, it is crucial to stick with the practicing until you’ve mastered the repertoire.

Renew and Maintain your Repertoire

What does your repertoire list look like? If you don’t have one, just jot down all the pieces you know. Perrin always has her students write three lists: pieces they are maintaining, pieces they are learning, and pieces they would love to play. Taking into consideration the student’s level and goals, Perrin then helps them compile a repertoire list the student can use when setting up their practice time.

When you’re practicing repertoire, you can revisit old pieces. Perrin notes, “When you first learned a piece, your technique level at the time may not have been high enough to be very comfortable with parts of the piece. So it is important to forget any bad habits you may have taken at the time and build new good ones. It’s challenging to pick a piece back up, as we usually want to play it at the same speed we left it. But the secret to improving it and taking it to a new level is to relearn it as a new piece, which means very slowly building up the final tempo. Here also table work helps to take a fresh look at it. You will most surely discover details you had missed the first time you learned it.”

3—The Contradiction of Practicing Improvisation

The survey included two improvisation questions, regarding repertoire and technique. They motivated participant Stina Hellberg Agback to observe her practice thoughtfully. Hellberg Agback holds a bachelor’s and master’s degree in jazz performance, from the Royal College of Music, Stockholm. She has also attended Berklee College of Music and Trinity College of Music. Since 2006 she has performed as an improvising harpist and also performs classical music with Uppsala Chamber Orchestra and Stockholm Wind Orchestra.

In her final interview, she noted, “The year of answering weekly surveys really got me thinking about how and what I practice, especially for my improvisational concerts and recordings. Practice for improvisation is in itself a contradiction, however I have started to develop different tactics for practice and found some ways to prepare for these concerts that I don’t think I would have figured out without the survey.”

For an improvisation gig, Hellberg Agback practices pieces that demand control over her technique, turning to early music because the strict chord combinations in baroque music are similar to jazz. She also returns to the wisdom a teacher offered years ago, advice she brushed off. Now she uses it all the time. “My jazz teacher told me to slow it down and improvise in slow motion. Pretend it’s super fast and cool but play it in slow motion so you can take care of the sound. He was right. It works.”

4—technique awareness

Some harpists are card-carrying technique nerds or etude junkies. Others only practice technique in the context of the piece they’re practicing because they have to. Regardless of your approach, it’s important to remember that technique is a crucial tool for any musician. In fact, learning and improving technique is a fundamental part of playing the harp. Teachers often tie technique practice to new challenges in a piece of music, making it more relevant and effective.

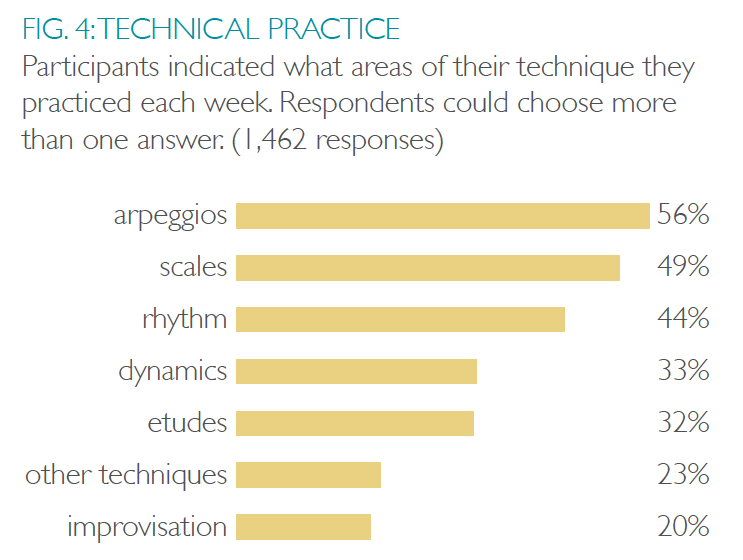

Each week participants selected up to seven types of techniques they practiced throughout the week (see figure 4). The goal: to see if participants increased their technique practice with each weekly check-in. In short, the changes weren’t large enough to be significant.

Some participants found that tracking their practice made them more aware of technique. Participant Erika Lieberman has played harp professionally part-time for twenty years, weddings for the bread and butter work and renaissance fairs for the music that resonates with her. She is a single mother and short on time, so she finds it easy to let dedicated technique practice slide.

In the final interview she said, “I don’t really think of it as practicing, it’s simply the preparation that I have to do for the gigs that I’ve got coming up. Although I don’t often make the time to actually improve my technique, having the weekly emails were great reminders to put in that time.” However, while Lieberman may not have time dedicated to focused technique work, she constantly worked on it within the context of her repertoire practice.

Build Solid Technique

Think of each technique as another tool that helps you build your pieces. Just as you have no hope of putting together an IKEA dresser without an Allen wrench, you won’t manage Clair de lune without using rubato and duples. Perrin notes, “You can’t play music without technique. You can do whatever you want. You can be as musical as you want. But you need technique to reach a very high level; look at any top musician.” Technique helps harpists learn pieces faster. For example, if you can play a scale of quarter notes at 138 beats per minute, then every time this appears in a piece of music, you don’t have to worry about it; you’re free to focus on the music without hours of extra practice.

Set aside a portion of daily practice to develop your technique toolbox. While you practice, Downie and Perrin suggest focusing on the areas where you are weakest. Perrin points out, “We all have different hands, so some techniques we will find very comfortable and others will be uncomfortable. For example, some people can trill easily without even practicing when other people struggle.” Dowine also notes that good technique can help prevent injury and pain.

Find the Positives in Practice

One question on the weekly survey didn’t have a strategic reason or measure; it was simply there to help participants see the positive side of their work: “Tell us something positive that happened in your practice this week.” Participant Tosca Tavaniello has played harp professionally since finishing her master’s in harp performance in 2021. In her final interview she said, “Sometimes we have a tendency to not be satisfied with our practice and we push for more. It’s important also to notice what we’re doing that works.”

Three quarters of the participants answered the question each week, and each of the more than 1,000 responses gave a window of insight into the participant’s week. Here are a few answers:

- “My husband let me have two hours in the morning on Saturday to practice without kids in the house. It was glorious.”

- “This is important: for the first time in three years after getting back into the harp I finally felt an emotional connection while I was playing. Up until now I’ve just felt like I am copying something I see on a paper. This was the first time it felt like the song was being played correctly and also coming from a deeper part of me. It was amazing.”

- “Had a good break from physical practice and found other ways of practicing, away from the harp.”

- “Brought an old piece back to life!”

- “Chose to stay positive and organize myself to achieve what is possible to do.”

- “Bought Ailie Robertson’s Technical Exercises book and started working through it. Her notes on fingerings for crossunders were extremely helpful, especially the last few on unusual fingerings.”

- “Revisited some music I learned but never firmed up and made a practice plan of what I want to work on. Some came back to me easier than I expected.”

- “Improved on identifying productive and achievable goals.”

- “Composed a wonderful piece in just one week. I am so happy about this!”

- “Just felt like I got into a rhythm with reviewing passages learned years ago. The more etudes and technique work I do, the more easily pieces fall into my hands.”

Remember to be kind to yourself as you practice. Perrin suggests, “If playing in an orchestra, you never play your best with a conductor yelling at you, but you will with one who praises and encourages you. In practice, we have to be nice to ourselves: if you won’t say it to a friend, don’t say it to yourself. Maybe it wasn’t the best, but it was better than a week before—note what you’ve achieved.”

5—guided goals

Most of us have tried to make New Year’s resolutions at some point in our lives. According to Forbes, 80 percent of those resolutions fail. In general, New Year’s resolutions are big sweeping, habit-changing goals which don’t take into account the many small steps needed to even start on that path.

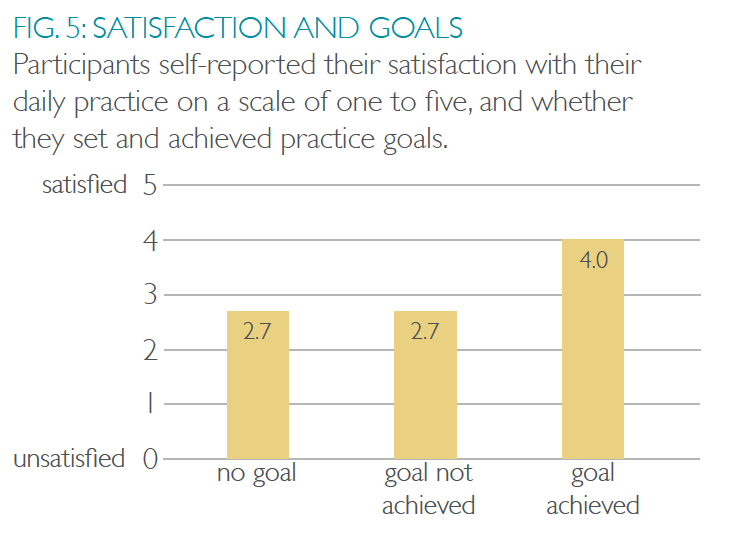

In the survey, participants answered three questions related to goals.

- Did you set practice goals?

- Did you accomplish most of these goals?

- How do you feel about your practice this week?

The results are clear: those who set goals and achieve them are happier with their daily practice. However, those who set a goal, but didn’t achieve it had the same level of dissatisfaction as those who had no goal (see figure 5).

Carefully made goals can support and guide practice. Downie uses goal setting with all her students. “You have 101 distractions, so much repertoire, techniques, types of music—if you just sit down at the harp every day and say, ‘I’m just going to practice,’ the result is likely playing a bit of everything, and you’re never really going to progress.” It’s an issue she often sees with her adult learners. “I can’t recall the number of people who have said to me ‘I’m just not improving. I’ve played for years, and I’m still a beginner.’ By not having clear, defined, smart, measurable goals, they’re often unable to progress in a satisfying way. They also can’t look back and assess what they’ve done because there’s no measure with which to celebrate their successes.”

Make Goals you Can Reach

Downie uses four steps when setting goals.

1. Find your motivation. The first step is finding what about music moves and excites you. Take a page and draw or write down what you love about music. Keep this page to look back on because you will, at some point, hit a wall in your practice. This page is to help you remember why you play.

2. Make manageable goals. This is one of the most difficult things for people to do, especially if you don’t work with a teacher. Unfortunately, people tend to reach for goals that are too advanced. Make your goal and set the timeline for how long you think it will take. If you’ve not set goals before, then double the time you think it will take. Finally work backwards, breaking things down into steps, so you know the one and two week actions needed to reach the final goal.

3. Adjust along the way. Remember, if you’re not keeping up with the goal timeline, you’re not failing. Rather, you’re learning how fast you can work. Take that learning and adapt the timeline to something that you can achieve.

4. Keep a record. Keeping a practice journal adds structure to practice by setting weekly goals and noting achievements. Downie encourages students to journal about their practice, “Not just what’s right or wrong and a list of things to fix. Include how long you’ve worked on techniques. Note how you feel, what went well because of this and didn’t go so well because of that, and next time I’m going to do this. Over time students develop a better understanding of their own practice approach, by journaling and reflecting.”

Perrin could have predicted the results of the goal-setting survey question. “People often set goals too high. Sometimes having overly high goals gives us excuses for not getting there. We need to find small steps that we can actually reach.” She also asks students to keep a weekly journal with goals so they can see their improvements and plan long-term work. Each week they use the star system, giving each piece they work on between zero and five stars, five stars being the performing level.

Keep in mind performance level means aiming for a perfect piece in practice. Performance is another story. Perrin says, “A lot of us try to perform at over 100%. But sometimes that makes us do exactly the opposite of what we want to do. An audience is not going to hear the difference between 80 percent and 100 percent. But for us, it will make a huge difference. One of my students was quite demanding of herself, setting really high goals, sometimes too high. She was always unhappy with herself because she could never reach what she wanted. I told her to aim for 80 percent in her performance. She gave one of her best performances, she smiled and she was happy and so relaxed.” Again each person is different so this won’t hold true for everyone. However, it’s worthwhile to remember that when you demand too much of yourself, it can actually make you perform worse.

Practice Made Perfect

The secret recipe for practice success is…individual to you. You have to build your own recipe and constantly adjust it as your life and playing change. Perrin and Downie are both quick to point out how each student is unique and there is no fast track to perfection. There is, however, a wealth of advice and tips we can learn from. Try them and see if they fit you.

Take small, achievable steps as you adjust your practice routine. Setting the bar too high is setting yourself up for failure. Keep learning and trying new things. Take inspiration from survey participant Rob Banks. He continues to grow in his harp practice journey of 50 years and counting. Now retired from his roles as a public library chief operating officer and principal harpist at the Topeka Symphony, Banks notes, “Once, I practiced eight hours a day. What I know now about practicing and what I knew then are so completely different, I probably would now approach eight-hours practice in an entirely different way. During this year I have studied up on the latest research on practice techniques and how you really can accomplish more with less blood sweat and tears than I did at that point in time.”

As you continue on your practice journey, keep Downie’s advice in mind: “Remember to have fun with your music, because that’s why we started, isn’t it? To enjoy the harp.” •

Author’s note: A special thanks to all the harpists who submitted 1788 surveys. Please know that I read every comment you wrote and you all inspire me. Thank you to Harp Column for supporting this journey. The Practice Makes Harpist survey was a case of curiosity getting out of hand during the pandemic. Shortly after launching the surveys I landed a full-time job. Unfortunately, there isn’t the capacity for a more science based paper, hence the word ‘study’ was changed to ‘survey’. For a little background, I worked with Brigham Young University harp professor Nicole Brady to define the questions, and a research scientist to test my methodology of processing the data. Now, please excuse me. I’ve neglected my own practice while researching and learning how to program Excel Spreadsheets. I’m eager to have more than a strategically planned 15 minutes a day with my harps.