—by Erin Wood

How long have you and the harp been a pair? Four years? Forty? Is your answer just a number, or does it reveal anything deeper about you—your skills, your outlook, your musicianship, or your relationship to your instrument? We wanted to find out a little bit more about what’s behind those numbers we toss out when a curious onlooker asks how long we’ve played the harp. Whether they’ve been at it for two years or 62 years, the harpists we talked to have plenty of observations to share about their years with the harp.

1st Decade

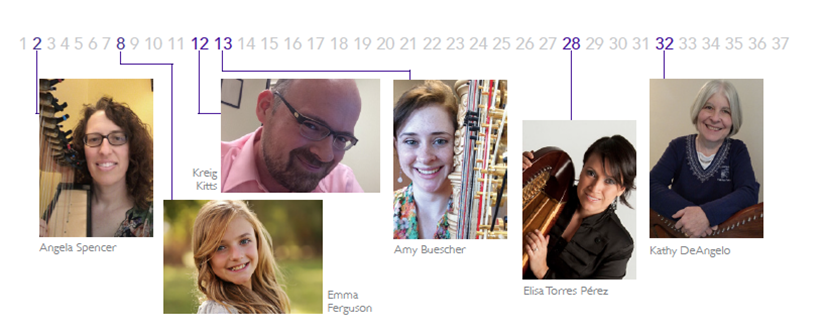

Anyone who has played the harp knows the learning curve in the first few years is a steep one, no matter your age when you started. Longtime choir and piano teacher, Angela Spencer decided it would be fun to try a new instrument, and a bright pink Harpsicle was her gateway into the harp world. She knew that her perspective starting at age 50 would be different than when she started piano at 7, but with her music reading skills and efficient practice habits, she progressed quickly. After a few months she was ready for a larger instrument. She says that unpacking her fully levered Dusty Strings Ravenna was a thrilling moment. While she didn’t have to contend with music reading and learning how to practice, Spencer says hand position was the biggest challenge at first. “As a pianist, it seemed very unnatural,” she says. “Although it seems simple now, I remember thinking that my hands would never be able to play those huge intervals.”

I think what draws me to the harp each day is the relaxation and enjoyment in playing, but what keeps me there is the music.

—Angela Spencer

After playing for just a couple of years, Spencer performs regularly at church and in retirement homes, and she loves to play Pistache by Bernard Andres. “Practicing the harp is to me what recess is to an elementary student. It is a part of my day that I always enjoy,” she says. “I think what draws me to the harp each day is the relaxation and enjoyment in playing, but what keeps me there is the music.”

At age 12, Emma Ferguson has already played the harp for two-thirds of her life. She remembers sitting on a tall chair boosted by two phone books wrapped in gold duct tape for her first recital at 4-and-a-half years old. Eight years later she can now comfortably sit behind the harp, but one of her biggest challenges is her small hands as she tries to grasp the many large eight-finger chords when playing one of her favorite pieces, Grandjany’s Aria in Classic Style. Though her harp studies have taken off, Ferguson says there was a period of time when the initial excitement of playing the harp wore off, the daily discipline of practice was challenging, and she wanted to quit. “My teacher at the time was very focused on my technique, and would not let me move on to the next piece until the prior piece was perfect. I would get so frustrated with a simple piece I had been working on for many months, and could not move on from!”

A turning point in her early studies came when Ferguson played at a nursing home with her older sister, a violinist. “For the first time, we were able to experience the intrinsic joy of making others happy with our talents that we had worked so hard to develop.” Still in her first decade with the instrument, playing the harp and performing for others brings her so much happiness, that it has become her passion.

2nd Decade

If you make it out of your first decade with the harp, chances are you begin to wade into the waters of what it means to be a working musician. Sometime during your second decade, your mindset shifts from student to professional. Amy Buescher has played the harp for 13 years and will graduate with a degree in harp performance this spring from Arizona State University. She says to be a harpist today “you have to work hard, you have to be willing to try things you never thought you would try, you have to actively pursue your musical goals, and you have to carve out the space to remember that you enjoy what you are doing.” She notes that harpists coming up behind her enjoy the benefits of increasing exposure to all things harp—from performances to music scores—thanks to the burgeoning body of multi-media material on the internet.

Kreig Kitts, who began as an adult and has played for 12 years, agrees that the prevalence of the harp today, thanks to easy media sharing on the internet and popular artists who feature the harp prominently in their music, makes for a different experience for would-be harpists than he had. “One reason there are so many adult amateur harpists is that we didn’t have the option to learn it when we were younger. Growing up, the only time I ever saw or heard a harp in person was at one wedding. Now young people can hear so many harpists, and it can appear on a kid’s radar much earlier.” Though he is in his second decade playing the harp, music is not his chief profession, which, he says, has advantages and disadvantages. “Having a full-time non-musical job limits my ability to practice regularly and have the chops for some repertoire, but the advantage of not needing to play for a living is the freedom to play anything I want.”

During the second decade when many harpists are beginning to turn from studying to producing income, Kitts’ perspective is an interesting one. “Something we tend to take for granted when in school is that our main responsibility is learning new things,” he says. “When that is no longer the case, you have to go out of your way to keep learning, especially when it doesn’t help meet material needs.”

3rd Decade

After 28 years of playing the harp, Elisa Torres Pérez has come full circle, in a way. She now teaches at the Puerto Rico Music Conservatory—the same school she began her studies at age 7. Pérez is also the first Puerto Rican to hold the post of principal harp in the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra. “Even though you never stop being a student as a musician, I feel that I passed from being a student to being responsible for building next generations of harpists,” she observes.

Pérez says teaching has taught her a lot. “I now pay more attention to phrases, musicality, without being afraid of taking long pauses or digesting the music.” In her third decade as a harpist, one of Pérez’s responsibilities is also one of her greatest challenges—building a harp community in the middle of a harsh economic climate. “I believe that it is necessary to stay active performing, teaching, and getting people to know the instrument and its beautiful qualities.”

4th Decade

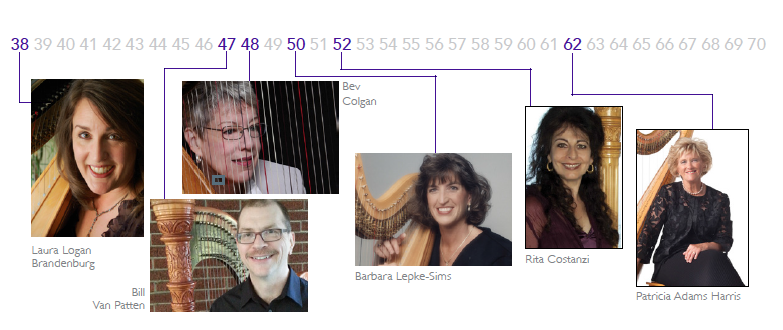

Three decades deep and counting with the harp, Laura Logan Brandenburg says she has found the keys to success as a harpist to be versatility, flexibility, and self-sufficiency. You have to be an ambassador of the harp, she says. Brandenburg teaches at Texas Christian University and is principal harpist of the Lewisville Lake Symphony, in addition to playing her own arrangements with her duo partner and a full slate of freelance gigs and private teaching.

The versatility and flexibility required to be a harpist extends beyond the instrument into personal life—especially when raising kids enters the equation. As Brandenburg taught students out of her home, her boys grew up seeing first-hand exactly what their mom did for a living and the preparation and work required to play and teach the harp. “They can still sing all the Suzuki harp songs they heard, over and over!” she says. Brandenburg made concerts and harp trips a family affair, something she thinks benefited her kids. “It broadened their education and enhanced their life experiences,” she says. “The harp was always part of their lives, too, and our life together as a family.” A key component in finding the harp-life balance is simple, according to Brandenburg: learn to say no to things you don’t want to do. This is certainly a lesson that is hard to grasp earlier in your harp life, when snapping up everything that comes your way seems like the only way to go.

Kathy DeAngelo is probably best known as the longtime director of the Somerset Folk Harp Festival, which draws hundreds of lever harpists each summer to New Jersey. She says the landscape for aspiring harpists is fundamentally different from what it was 32 years ago when she began. “The internet didn’t exist when I started playing, and I really believe it has shaped how musicians can develop themselves as players,” she observes. “There was nobody around me playing harp back then, and I knew the only way for me to play with other harpers was either for me to create opportunities, which is why I became a teacher, or make a place for harp lovers to get together, which is why I started the Harpers Escape and now direct the Somerset Folk Harp Festival.” DeAngelo plays many instruments in the Irish band McDermott’s Handy and has a level of enthusiasm about playing the harp that is reminiscent of a starry-eyed beginner. “This is an incredible time to be a harper,” she says. “There is so much music and inspiration out there and so many opportunities to meet and rub shoulders with great players and be inspired by live performances.” Harpists of any age can aspire to this outlook.

5th Decade

Barbara Lepke-Sims has been playing the harp long enough to see distinct phases of her life as a musician. After graduating from Juilliard with her master’s degree, she held down an orchestra job in addition to playing every gig that came her way. Then came a more stable period of teaching full-time in a school system while still gigging and teaching harp lessons. Now retired from the school system, Lepke-Sims works as a therapeutic musician. She has played lever harp in hospitals since 2009 and is the area coordinator for a therapeutic musician training program. She also volunteers with the American Harp Society on both a local and national level.

Over the years she says she has learned that it is important to not get so hung up on perfection and to just enjoy the music. “Juilliard trains you to strive for perfection so that you can win competitions and get that perfect job. Unfortunately, in the process of striving for perfection, sometimes the joy of playing the music and the harp gets lost in the process.” Lepke-Sims says shifting her focus from perfection to the enjoyment of making music is one reason she enjoys playing therapeutic music at this stage in her life. “The emphasis is on the patient, not myself. It is not a performance but an act of service.”

I was thinking that it was all about technique and talent. Those are obviously required, but the other things sometimes have made the biggest difference.

Bev Colgan

Whether carting her harp up a mountain on a ski lift for a wedding, playing jazz harp and vibraphone duos in a recital with her husband, or being complimented by Pavarotti during a rehearsal with the Reno Philharmonic, Bev Colgan has loved playing the harp ever since her first lesson in 1968 when she learned “Big Brown Bear.” Colgan says early in her career a master musician told her, “Be on time. Be in tune. Know your music. Be a good citizen of the orchestra. And you will always work.” She adds, “I was thinking that it was all about technique and talent. Those are obviously required, but the other things sometimes have made the biggest difference.”

Colgan says that, at this stage in life, it is important for her to remember she can’t take anything for granted. “Thinking Oh, I’ve played The Firebird 500 times. How hard could it be? is a tempting trap.” She says she strives to always be engaged and “be true to the music and play it as well as I can, whether it’s Mahler or Meghan Trainor.”

In his mid-30s, Bill Van Patten was tired of being a poor and uninsured harpist and took a job in the “real world.” He ended up being more successful than he expected, and without meaning to, the harp took a back seat. He says, “At first, it was nice to have a sabbatical—and a regular paycheck—but I missed the feeling of purpose and the fun of performing.” Today Van Patten and the harp are back together again, having found a good balance between day job and harp life. In addition to his day job, Van Patten is the principal harpist of the Washington (Pa.) Symphony, serves on the group’s board of directors, and is secretary of the Pittsburgh Chapter of the American Harp Society, embracing the challenge of balancing the responsibilities of two very different worlds. “There is a good deal of my sense of self that is all about being a harpist. But having had success in the business world as well has made me realize my identity is me, not any of the jobs I’ve had—whether musical or corporate,” he says. “I also know from having taken a sabbatical from the harp that truly, it is easier for me to just give in and play the darned thing than to try to pretend I don’t want to.”

6th Decade

Over her 52 years of playing the harp, Rita Costanzi says performing has become easier because of the lessons she has learned. “I do not need to be the best harpist in the world: only the best harpist I can be. Striving for perfection on stage is an unrealistic expectation. Perfection is important in the practice room, yes, but not on stage!”

Costanzi’s vibrant career was nearly deterred early on. “It was my summer at Tanglewood in the Fellowship Orchestra. Leonard Bernstein humiliated me in front of the orchestra during one evening rehearsal, and I was so devastated, so destroyed by the experience, that I said to my father: ‘If this is what the music profession is like, I am quitting now,’” she recalls. “I wept for an entire weekend and then, somehow, found the inner strength and resolve to continue. Music was my whole life—my passion, my identity and being. For me to even contemplate quitting was a measure of that soul-destruction and my own sensitivity as an artist.”

To say Costanzi has done it all in her career is closer to truth than cliché. She was principal harpist of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra and the CBC Radio Orchestra, she taught at various universities, and she regularly performed and taught internationally. But artistic growth came from an unexpected place when she began acting in 1996. “It brought a deeper and more powerful dimension to my harp playing and performances,” she says. Her most current project is working with actor, pianist, and producer Hershey Felder to assemble a one-woman theater piece about her life, which she hopes will bring the harp to new audiences in a unique and meaningful way. After a lifetime of waiting, Constanzi says the show is a dream come true. “Never let go of your dream,” she says. “Sometimes, it may take a whole lifetime for it to come true.”

7th Decade

In her seventh decade at the harp, Patricia Adams Harris is proactive about keeping fit. She plays tennis and does strength training twice a week to stay strong enough to move her harp. She also makes an effort to do more finger exercises and constantly works on technique and ergonomics. She even has different benches for different harps. Harris has been playing the harp for 62 years—52 of those years as principal harpist of the Tucson Symphony. Many harpists know Harris through her work on the executive board of the American Harp Society Foundation. Her father was a founding member of the Foundation, and he established the Anne Adams awards in 1990 to honor his wife, harpist Anne Adams. Patricia continues to work on the Anne Adams Awards that the Foundation sponsors every two years.

“I am passionate about the Foundation and all the good work we do,” she says. Harris has had many fine students over her teaching career, which has evolved. “[Now] I teach mostly older adults, which is great fun!” she says. “They want to play, and it keeps their brains working.” •